pro/POSIT collaboration with British Waterways on masterplanning of Brindley’s historic canal basins leading to design implementation and parallel commissioning programme, and Andrew Davis Partnership and others on detailed design for landscape works.

Heritage Lottery funded with additional funding support from Arts Council England-West Midlands, Wyre Forest District Council, and Arts & Business. Shortlisted for BURA Waterways Renaissance ‘Strategy & Master Planning’ Award 2006. BURA Waterways Renaissance ‘Historic Environment’ Award 2008 and ‘Outstanding Achievement’ Award 2008. Winner of ‘Best Heritage Project’ National Lottery Awards 2009.

2004–2006 Stourport Canal Basins Masterplan (as pro/POSIT)

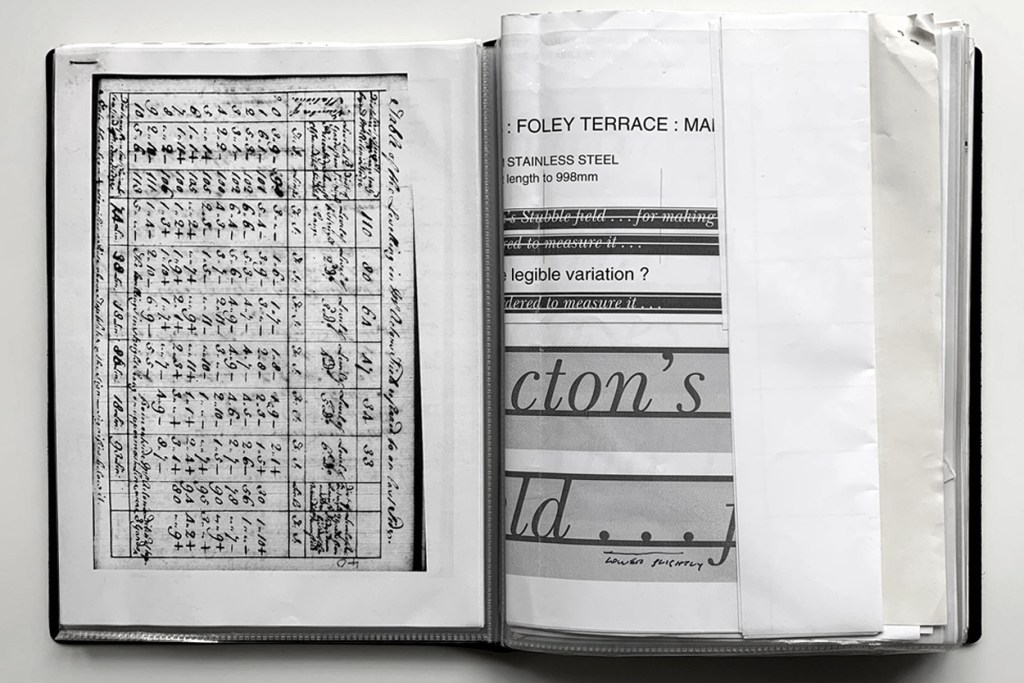

PDF: Stourport Sketchbook 2004–2005

PDF: 2004 Stourport Principles #3

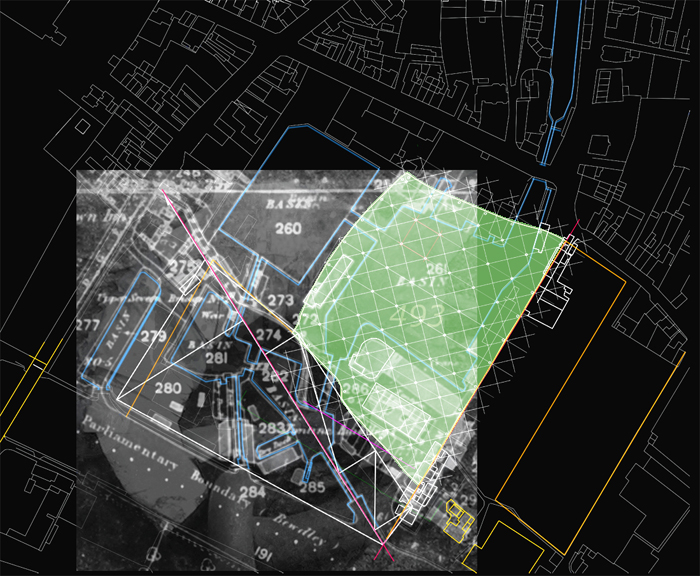

PDF: 2004 Stourport Geometries

PDF: 2005 Stourport Swing Bridge | (Armajani)

PDF: David Shrigley | John Fennyhouse Green Quote

Tontine Garden, August 2006

PDF: 2006 JFG at Lower Mitton 1768

PDF: ‘[a small] MONUMENT to John Fennyhouse Green’

07.07.2025

Stourport is a vibrant example of Jaspers’ existential philosophy in practice. The Stourport Canal Basins, as depicted in David Patten’s site [https://davidpattenwork.com/17-stourport-canal-basins/], can be richly interpreted through Karl Jaspers’ existential philosophy—especially his concepts of boundary (limit) situations, existenz, and encompassing.

1. Time as a Boundary Situation

Jaspers defines boundary situations (Grenzsituationen) as those profound human experiences—death, suffering, guilt—where we confront the limits of our existence and are compelled to transcend. Patten’s emphasis on time as “woven into the fabric,” eroding and revealing layers of memory and experience, mirrors Jaspers’ boundary. The canal’s evolution—its decay, its restoration—is a living encounter with history and finitude. Visitors are reminded of mortality and cultural loss, yet also of the potential for renewal—a Jaspersian moment of both limitation and transcendence.

2. Ruins and Restoration: Confronting Finitude and Renewal

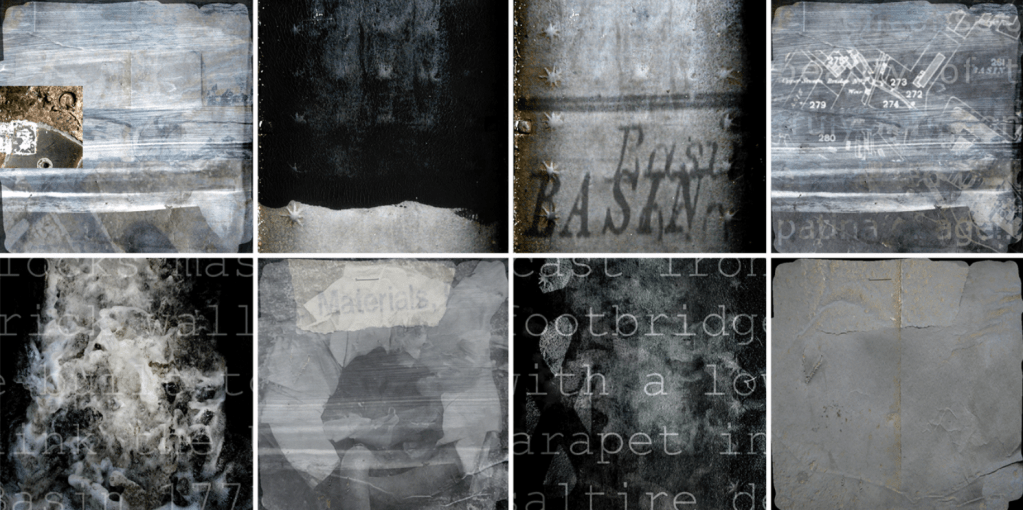

The site’s palimpsest of vanished iron warehouses, measured arcs in chalk, and exploratory drawing capture what Jaspers calls the confrontation with limitation and the subsequent inner elevation toward authenticity. The act of “measuring where a wall once stood” is a dialogue with finitude. Yet this recognition isn’t resignation—it prompts imagination and action, echoing Jaspers: an authentic existenz arises not from avoidance but engagement with limit situations.

3. Existenz and Authentic Engagement

For Jaspers, existenz emerges when we fully own our finitude and freedom. It’s living in the tension between the “realm of objectivities” and the “powers of the subject”. Patten’s practice—walking, drawing, conversing—becomes an embodied, reflective engagement. It is this existential communication, a mutual opening and transformation, that reveals the gestalt of the place: not a static heritage site but an active space of meaning-making.

4. Encompassing: Integration of Layers

Jaspers’ concept of encompassing (Einschließen) involves holding together boundary situations, transcendence, and existential communication into a unified perspective. Patten aggregates archival traces, lived experience, design interventions, and communal dialogue. His “world‑slicing” imagery and layered renderings act as acts of encompassing—they invite observers to experience the canal basin not simply as a landscape, but as a lived, layered phenomenon of meaning, memory, and possibility.

5. Dialogical Craft: Drawing as Thinking

Patten quotes Goethe: “talk less and draw more.” For Jaspers, authentic understanding arises not through abstraction but through engaged communication—with people and with place—stepping beyond the shell of habitual perception . Drawing is a dialogical method of knowing: measuring, marking, sketching reveal what was lost—and what could be reclaimed. It is existential communication in environmental form.

In Summary

- Boundary situation: The canal basins expose us to historical loss and mortality, yet open the opportunity to act and rebuild meaningfully.

- Existenz: Patten’s methodology invites individuals to fully inhabit and respond to the site’s contingencies, embracing both the subjective and objective.

- Encompassing: The regeneration masterplan unites past, present, and future; art, heritage, and community; enabling a comprehensive existential encounter.

Through Jaspers’ lens, Stourport becomes more than heritage—it becomes a lived existential site: a place where limitation sparks transcendence, where authenticity is built through embodied, dialogical practice, and where renewal arises through collective and reflective action.

Public Engagement & Jaspers’ Existential Communication

Jaspers emphasized existential communication—a mode of dialogue that demands vulnerability, openness, and equality. Only in genuine dialogue does truth emerge, and selfhood (Existenz) become visible.

Patten’s public-engagement efforts clearly resonate with this model:

- Vulnerability & openness: By sharing preliminary drawings, inviting local stories, and tracing archaeological arcs, Patten rejects polished, expert-only narratives. Instead, he positions himself—and participants—as equal explorers.

- Dialogical reciprocity: Workshops, walkthroughs, and communal measuring practices become co-creative spaces. People bring lived memory; Patten brings observational rigour. Together, understanding emerges—a hallmark of existential communication.

- Equality in participants: There’s no “expert reveal.” Diverse voices—historians, locals, planners—contribute in parallel. This egalitarian ethos embodies Jaspers’ ideal: truth begins in the “we”.

Through these engagement practices, the site becomes a living Existenz-space—not a static, preserved artifact, but a dynamic gathering site for shared understanding and meaning-making.

Public engagement creates a communal space of existential communication where those experiences gain meaning. The site transcends mere heritage; it becomes a crucible of lived authenticity and shared renewal. Engagement practices: not just outreach—they’re existential conversations. Site as Existenz-space: where limits, choices, dialogue, and renewal coalesce into active meaning‑making.

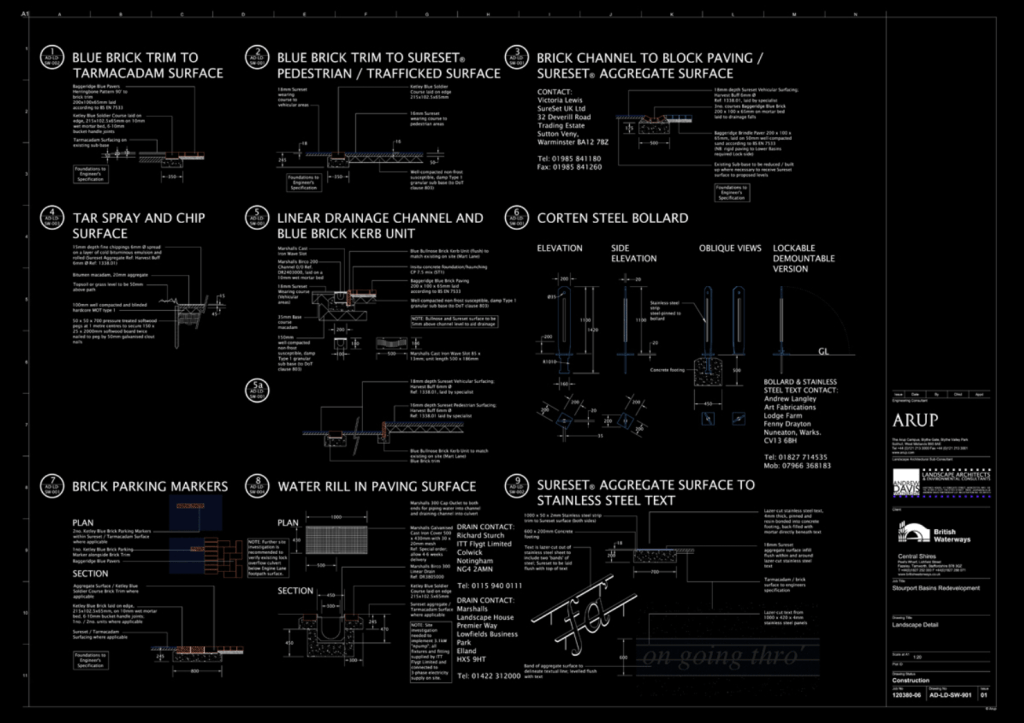

2006–2008 Stourport Canal Basins Detailed Design

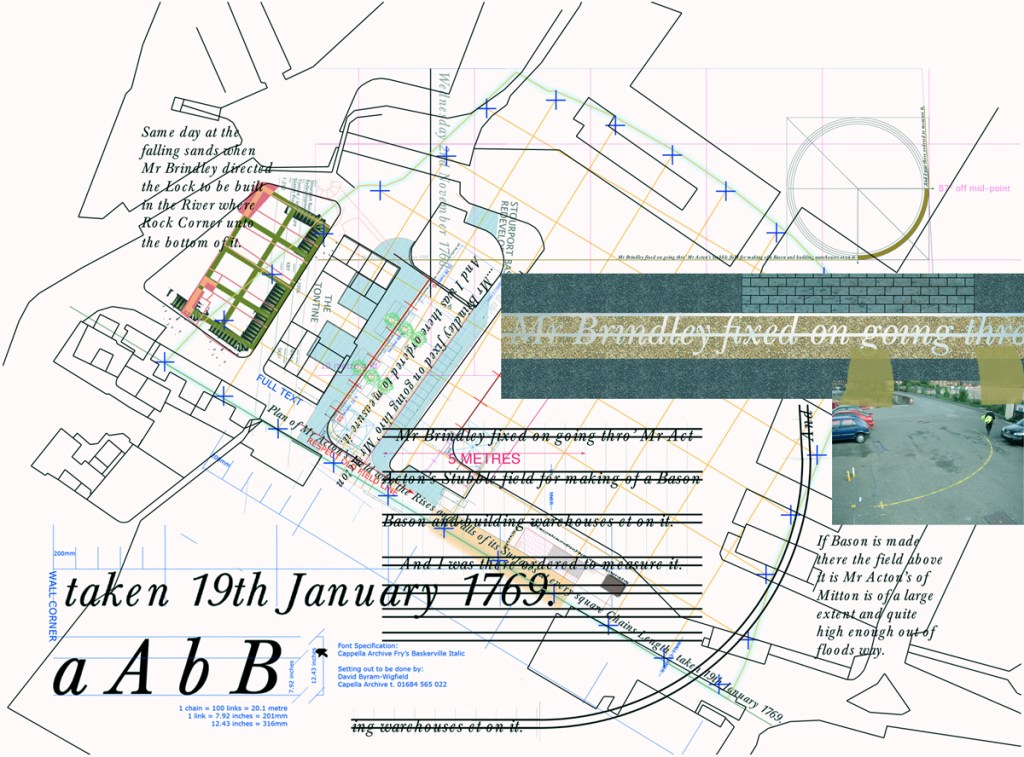

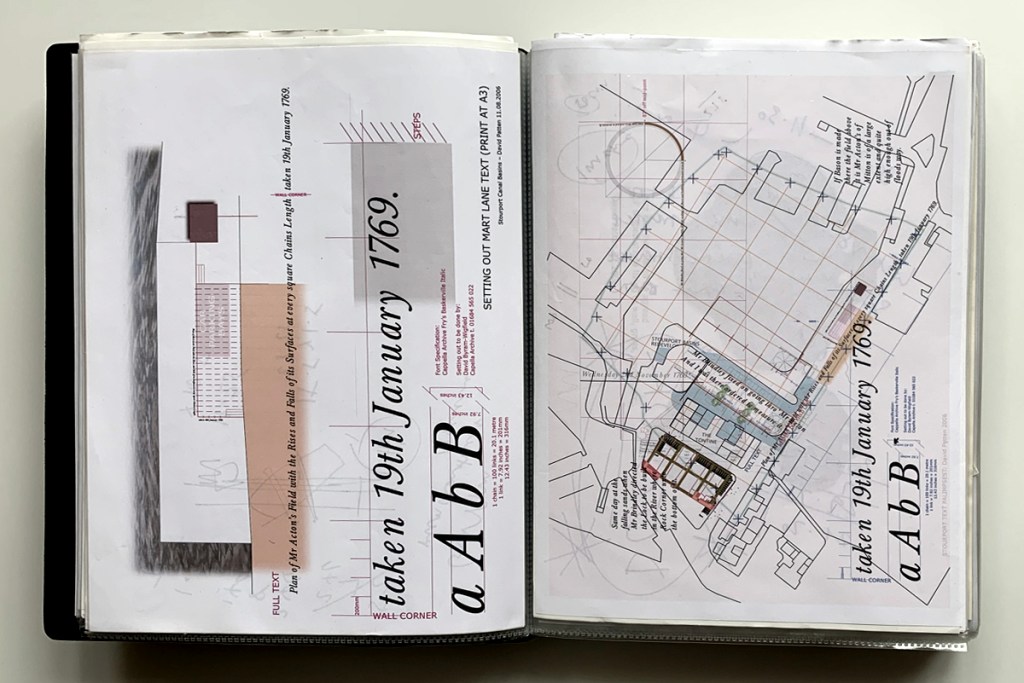

“Mr Acton’s Stubble field” | The text is the label, and the painting is all of the landscape ‘above’ it.

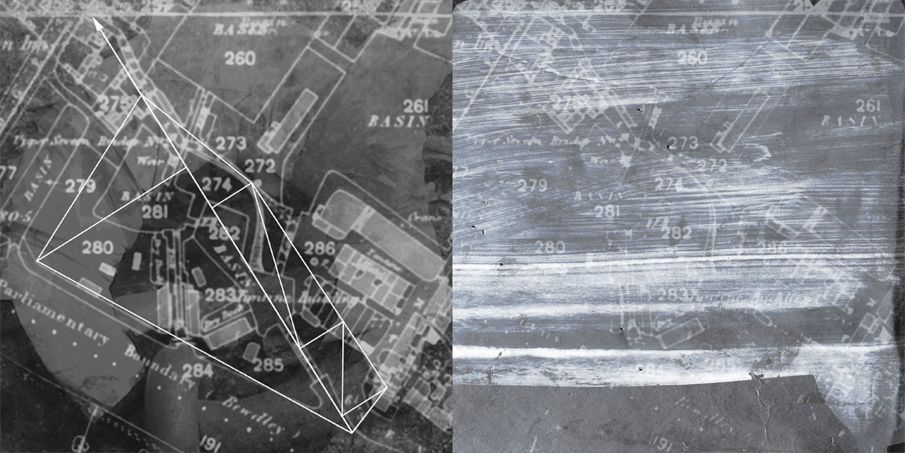

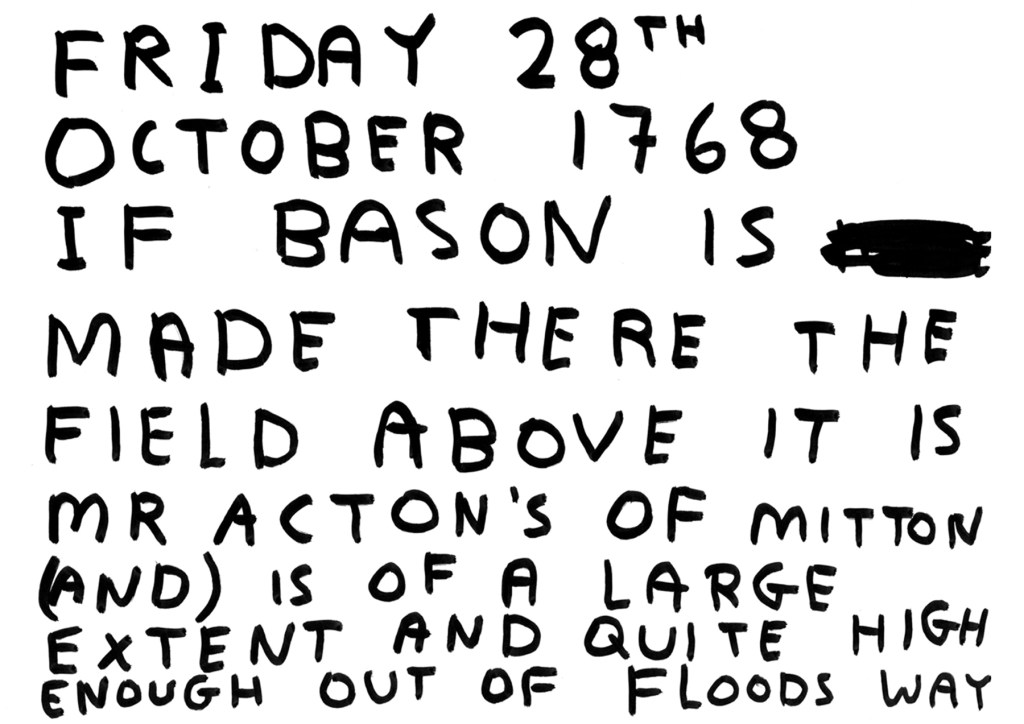

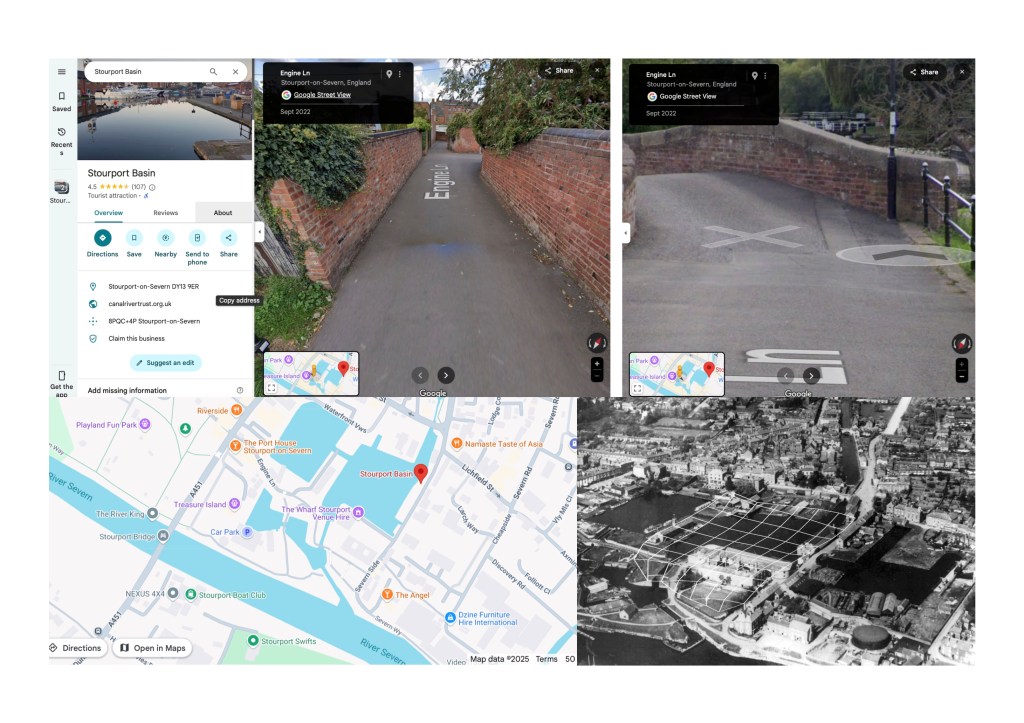

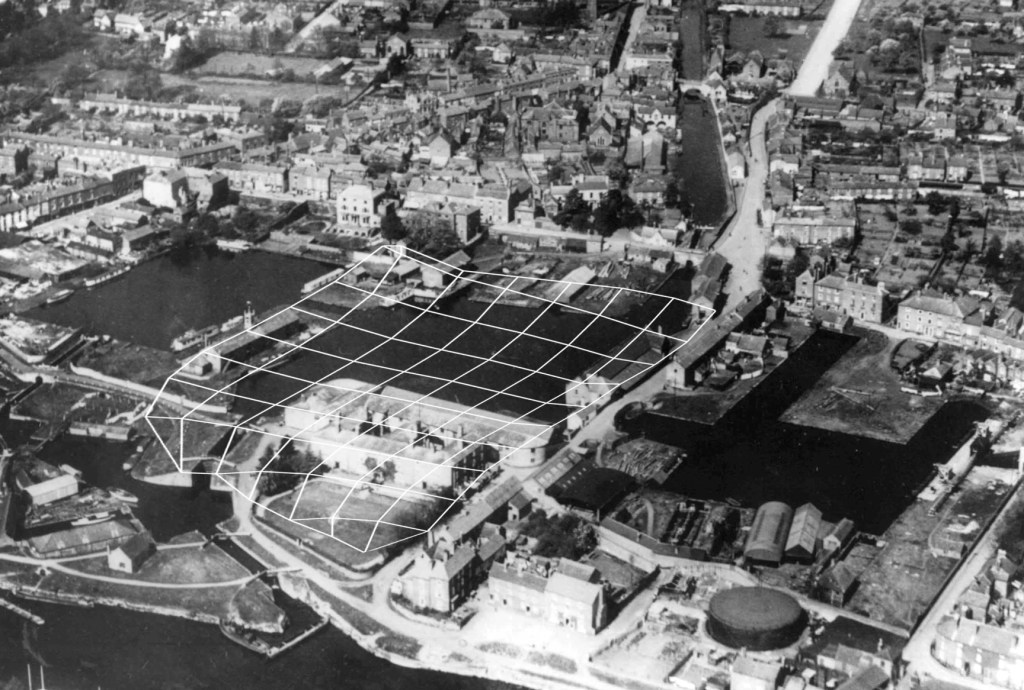

On the 27th October 1768, John Fennyhouse Green was assisting John Dadford in setting out a culvert at Broadwaters when John Baker, the Clerk of Works, directed Green to “go down to the Stour’s Mouth and observe where the Canal might be brought to the Severn.” In his Day Book for 1 November 1768, Green records his visit to “Mr Price’s at Stour’s Mouth” (now the Angel Inn) and to assess the potential of the immediate landscape as the location for the inland port, “If canal is bro’t above… If Bason is made there…” He was looking for a piece of land that was both broad enough to accommodate what is now the Clock Basin and which sat “high enough out of flood’s way.” John Acton, the local Church Warden at Lower Mitton, owned just such a field – a stubble field, measuring something over 5 acres (20,000 m2) and lying high enough above Mr Roberts’ meadow that ran along the River Severn.

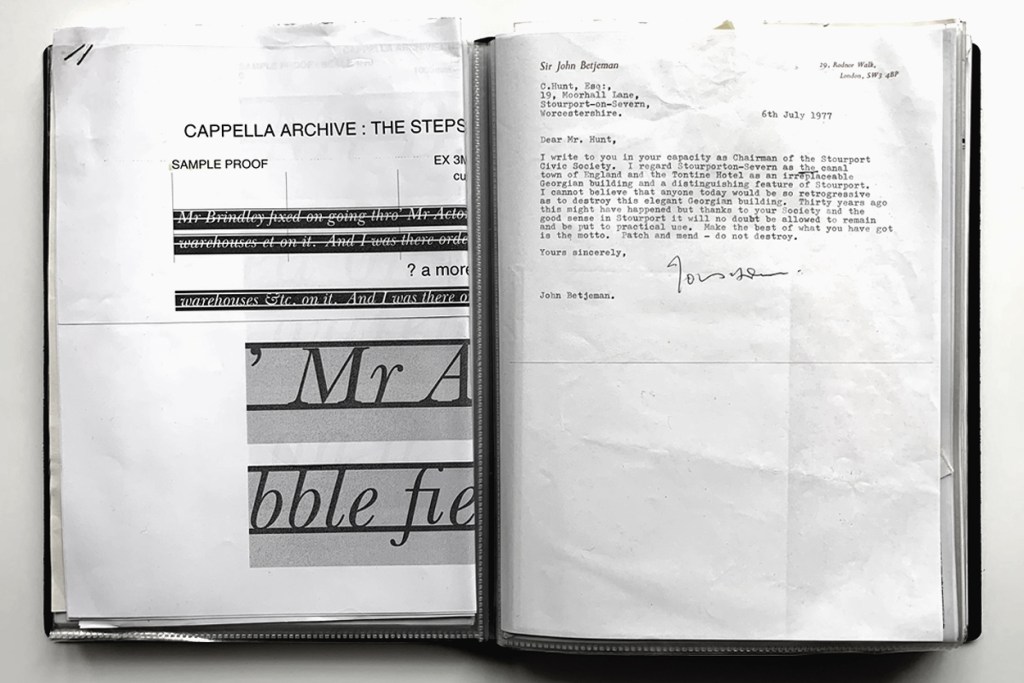

On Wednesday 2 November, Green met with Brindley and Sir Edward Littleton, Chairman of the Canal Company, at Acton’s stubble field to discuss his observations. The outcome of this meeting was that “Mr Brindley…fixed on going thro’ Mr Acton’s Stubble field above Mr Price’s House for making of a Bason and building warehouses et on it” and ordered that “the Setting out of the Canal and new Water course of 17th October be altered.”

PDF: 2006 JFG at Lower Mitton 1768

PDF: 2008 Monument to John Fennyhouse Green

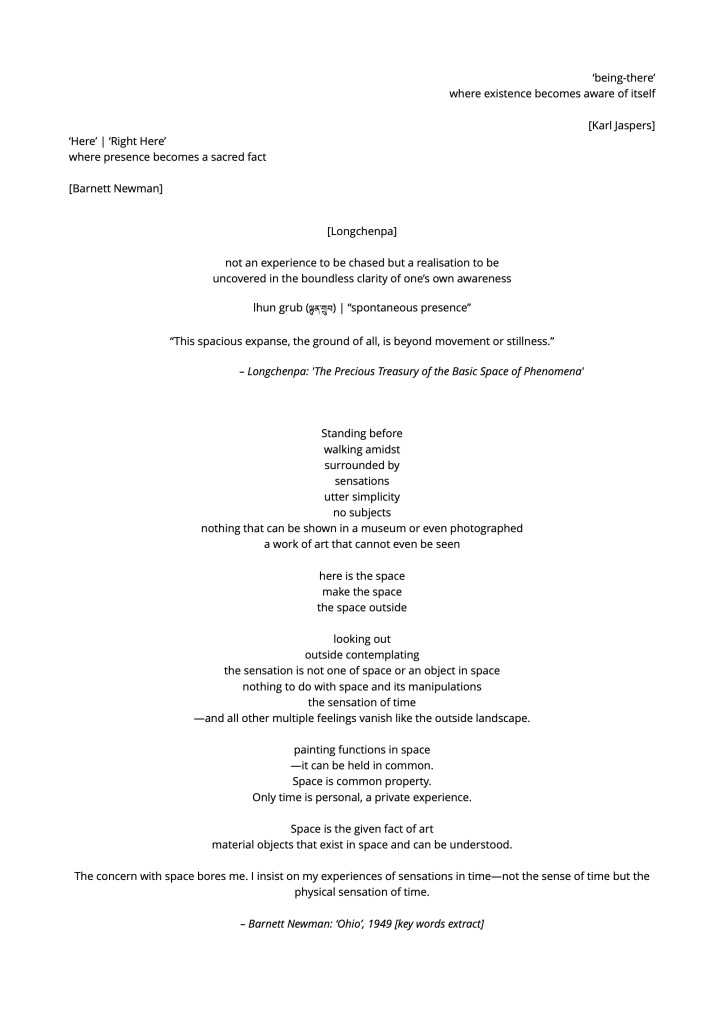

“A world picture, when understood essentially, does not mean a picture of the world, but the world conceived and grasped as picture.” [Martin Heidegger]

PDF: 2008 Stourport Memory Text

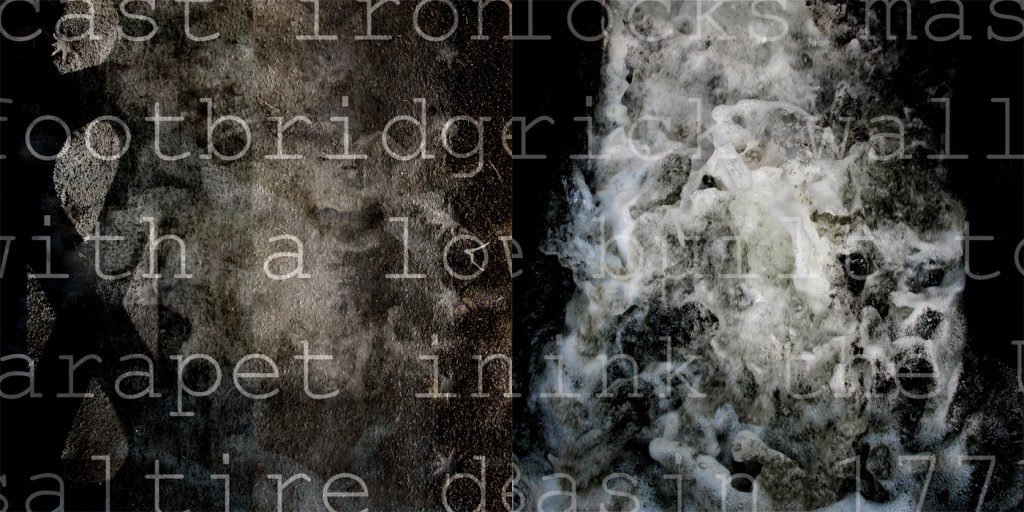

Only time would tell. Time is woven into the fabric of the Canal Basins at Stourport – it erodes the site but also opens up layers of content and memory and experience that enrich the place. As such, time bears witness to loss while providing the material for future recovery and revitalisation. And, as always, these things take time.

The important thing about walking the site together is not so much what we look at (although that is important) or talk about (although that is also important) but how bits of looking and talking become layered to suggest new possibilities. A looking and talking palimpsest excavating the layers of the site, exposing the incomplete erasure of the things that have gone and revealing the partial legibility of the things to come.

Alex said to Tom, quoting Goethe, “We ought to talk less and draw more.” Perhaps she had a point.

Certainly drawing is like thinking – and we think about everything. Drawing is about noticing things, generating and accumulating evidence, and about narrowing the gap towards future action. Like when we turned the corner at the Tontine and imagined the ghost of the curved wall of the now dismantled Iron Warehouse.

We stopped our talking and measured out where the wall had stood. An 8.75 metre arc chalked on the tarmac, locating something that had once stood over 6 metres high – obscuring the views up and down Mart Lane. And we understood, for the first time, the real scale and massing of what had been here.

“Throughout his career, (Barnett) Newman referred to his 1948 painting ‘Onement I’ as a moment of origin: “I recall my first painting–that is, where I felt that I had moved into an area for myself that was completely me–and I painted it on my birthday (January 29) in 1948. It’s a small red painting, and I put a piece of tape in the middle, and I put my so-called zip.

Although there were earlier paintings and drawings that consisted of a narrow, centralized zip in a monotone field, ‘Onement I’ was the first zip painting in which all three parts appeared congruently in a single field, rather than as a striped “figure” that divides a receding ‘ground’. After painting ‘Onement I’, Newman stopped making art for eight months.

In August 1949, he visited the Indian burial mounds in the southwestern part of Ohio, where he was profoundly moved by the sense of his own presence within the dramatically open spaces. He wrote, ‘Here is the self-evident nature of the artistic act, its utter simplicity. There are no subjects – nothing that can be shown in a museum or even photographed; [it is] a work of art that cannot even be seen, so it is something that must be experienced there on the spot….Suddenly one realizes that the sensation is not one of space or [of] an object in space. It has nothing to do with space and its manipulations. The sensation is the sensation of time – and all other multiple feelings vanish like the outside landscape.’”

– A. Kurlander: ‘Index of Selected Artists in the Collection’, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College

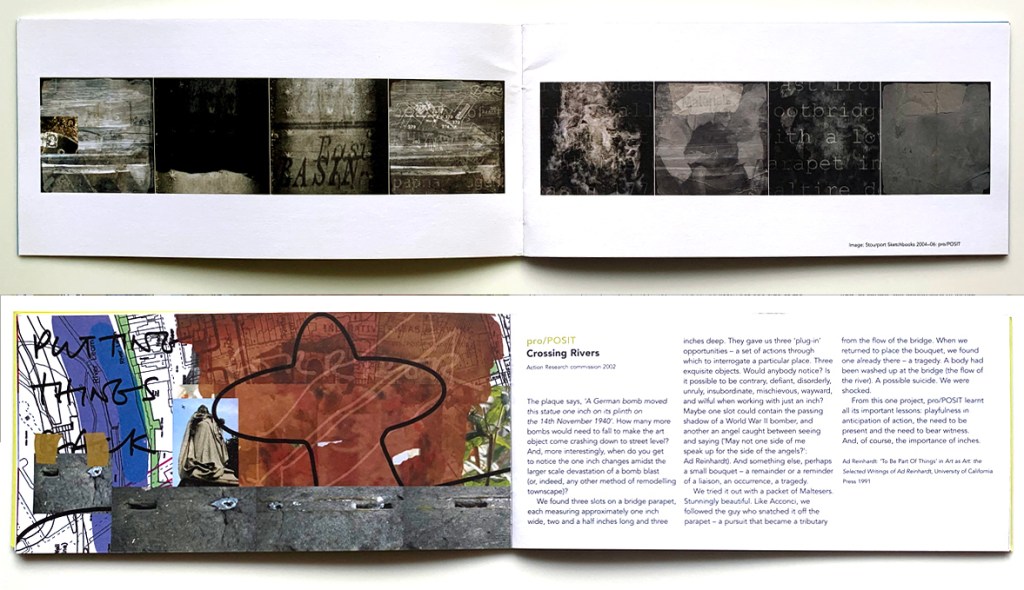

2001-2005 pro/POSIT (with Maurice Maguire)

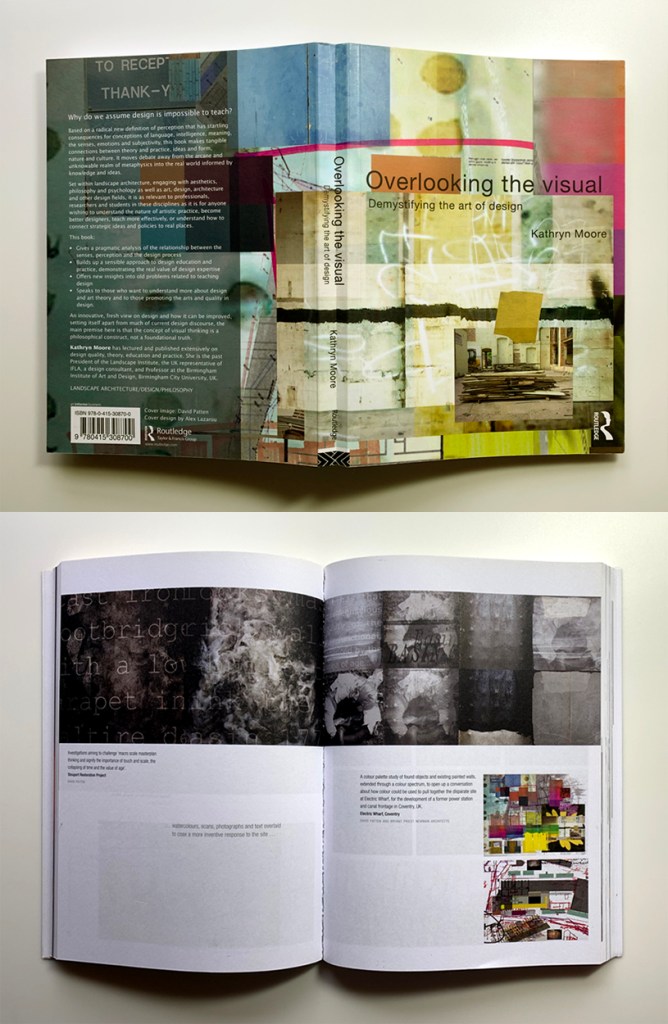

2009 ‘Overlooking the Visual’ (images)

PDF: Kathryn Moore, 2010

Other British Waterways Projects

1994–1995 (with Maurice Maguire)

Coventry City Council – Coventry Canal Corridor Public Art Strategy.

1999

British Waterways – IWACC Innovations Group.

2003–2004 (pro/POSIT)

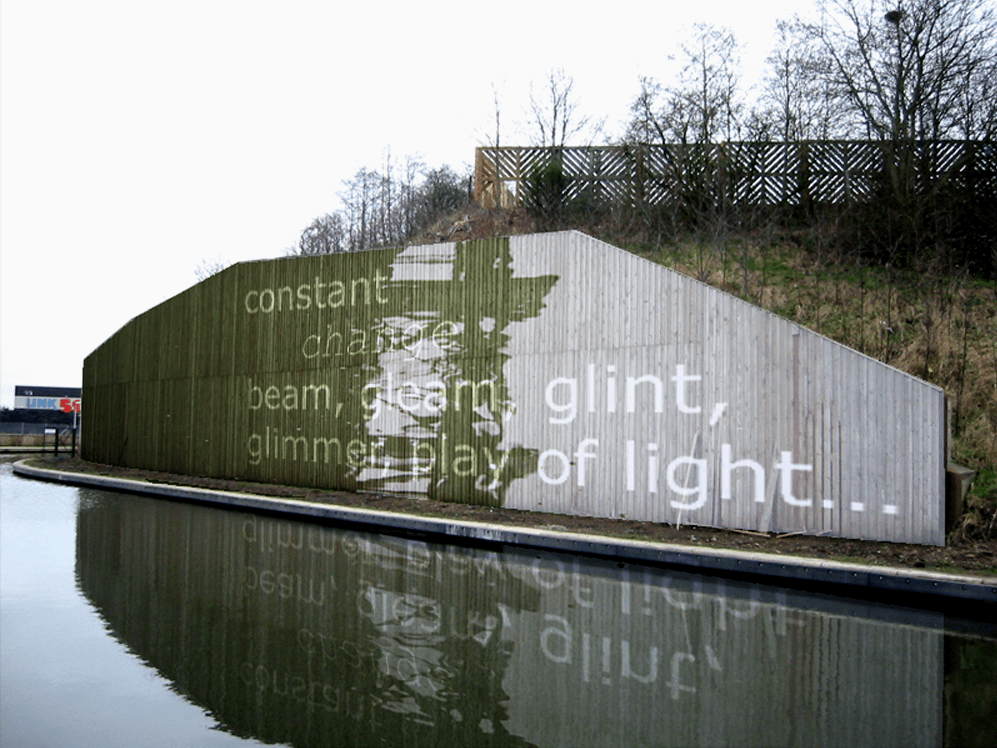

‘constant/change’ – appointed by British Waterways to contribute to the masterplanning process for the new Brierley Hill.