– Jeff Nuttall: ‘Bomb Culture’, 1970 (1968), p19 / V. E. Day 08.05.2020

Performance artist, poet, novelist, jazz musician, teacher, theorist, painter and sculptor, Jeff Nuttall is the only all-round genius most of us are likely to meet in our lifetime. And let the sceptic beware: this is no exaggeration. His talents usually control at the limits of human exuberance. His skills are both highly local and deeply embedded in European twentieth-century arts. In a culture exemplified by tepidly isolated skills, greed, pop repetitions and art trivia, Jeff Nuttall’s work is bracing and joyful, celebrating another world of values, ones that last.

– Eric Mottram: ‘Calderdale Landscapes’ exhibition, Angela Flowers Gallery, London, 1987

05.08.2019

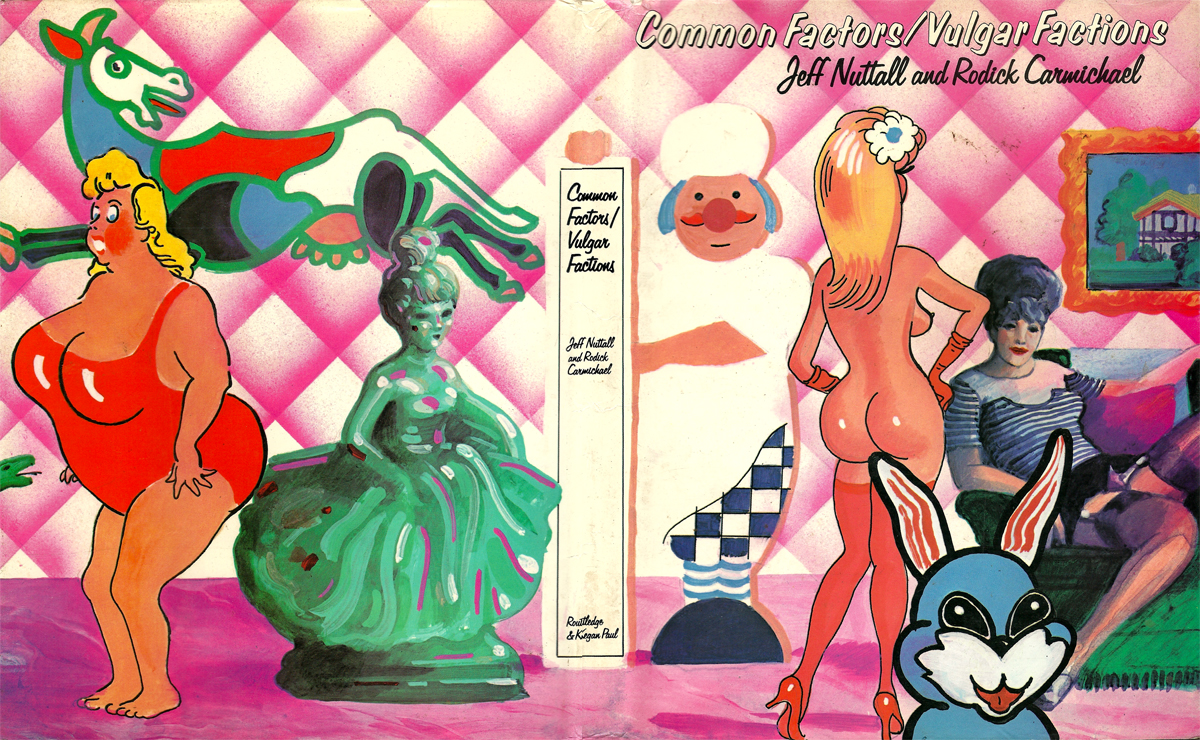

ESCALATION | The aristocracy is always dying. The top of the social tree is always falling away in twigs and powders and leaf-skeins.

– Jeff Nuttall & Rodick Carmichael: ‘Common Factors/Vulgar Factions’, 1977

PDF: Common Factors/Vulgar Factions

01.09.2019

PDF: JN | IT Archive

PDF: FOOT NOTES 19.01.1968 01.02.1968

02.09.2019

(3) See sketchbook in the coll. Miss Joan Ivimy, or repro, in “The Samuel Palmer Valley of Vision” by Geoffrey Grigson, Phoenix, 1960.

(Image Service order FI-001120363, 01.09.2019)

Front inside cover of a sketch-book of 77 sketches bound originally in sheep, inscribed with the artist’s name and address. c.1824 | ©Trustees of the British Museum.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 3

23.12.2019

(1) See “A RUSTIC SCENE” by Samuel Palmer, 1825. Coll. Ashmolean Museum.

(2) See “OAKS ON HAMPSTEAD HEATH” by Samuel Palmer.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 1

(5) See “BEING BEAUTEOUS” by Peter Redgrove in “The Penguin Book of Sick Verse” ed. Geo. Mac-Beth.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 5

(6) See “THE SPIDER” by Harry Fainlight in “Wholly Communion” Lorrimer Films Booklet 1965.

When tested on spiders, the drug tends to distort the symmetry of the webs they are spinning.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 6

20.03.2020

(7) See cartoon strip by me in INTERNATIONAL TIMES Issues 1–8, also “THE CASE of ISABEL and the BLEEDING FOETUS by me, Turret 1967.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 7

21.03.2020

(8) See 6th stanza from Part One of “MALDOROR” by Lautreamont, New Directions 1965.

(9) See 13th stanza of Part Two from “MALDOROR.”

“One should let one’s fingernails grow for fifteen days.” – Lautreamont

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 8 & 9

24.03.2020

(10) “If I were tickled by the hatching hair . . The itch of man upon the baby’s thigh I would not fear the gallows nor the axe . . “ from p.12 “COLLECTED POEMS” by Dylan Thomas, Dent 1952.

LINK: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H_ONQvjeOho

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 10

(4) See Fuseli’s drawings of courtesans made between 1805 and 1808.

Henry FUSELI (1741-1825) Switzerland, England, Two Courtesans with Fantastic Hairstyles and Hats c1790-92, pen with brown, pink and grey wash, Auckland Art Gallery Tou o Tamaki, purchased 1965.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 4

26.03.2020

(11) See “THE SICK ROSE” by Wm. Blake.

(12) See drawing in the Tate Gallery Collection.

Plate number 39 ‘The Sick Rose’ from ‘The Songs of Innocence and of Experience’ composed sometime between 1789 and 1794. Hand-coloured print, issued c.1826.

After the Albert Hall event I wrote to Klaus Lea crying: “London is in flames. The spirit of William Blake walks on the water of the Thames, sigma has exploded into a giant rose. Come and drink the dew.”

– Jeff Nuttall: ‘Bomb Culture’, 1968

(13) See plate in Gilchrist’s biography of Blake.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 13

(14) Compare “TEMPTATION OF ST. ANTHONY” by each of these artists.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 14

20.04.2020

(15) See pages 8 10 and 12 in “POEMS I WANT TO FORGET” by me, Turret Press 1965.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 15

07.05.2020

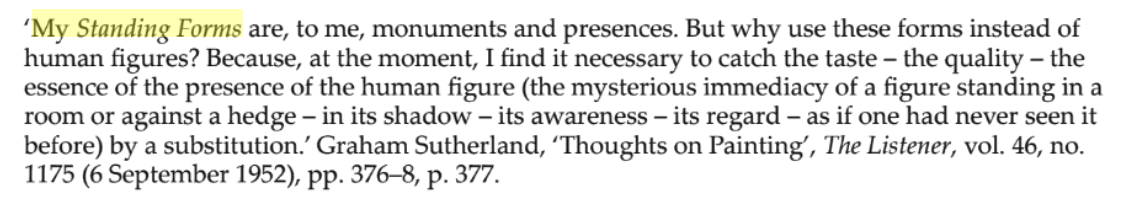

(16) See “STANDING FORM” by Graham Sutherland, Arts Council Collection.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 16

(17) See interview with John Russell in the SUNDAY TIMES colour magazine and in CAMBRIDGE OPINION No. 37.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 17

08.05.2020

(18) Romanesque Church, heavily decorated, between Hereford and Abergavenny.

“My intended detachment was completely destroyed. The building refused to be seen as an arrangement in stone, as the key to a time and a tradition, or as a piece in the jig-saw puzzle of art history. It stood unavoidably as a work of art, the timeless expression of a vision experienced under that same sun which now winked at me through the deep yew tree.”

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 18

(19) See “THE NEW BOOK / A BOOK OF TORTURE” by Michael McGlure Grove Press.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 19

10.05.2020

(20) Patricidal manic paint. English early 19th C. Both pictures in Tate Gallery.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 20

(21) John Clare, “mad” English poet of the 19th C., spent much of his time in Northampton Lunatic Asylum. Drawing of him by a fellow patient is in the possession of Northampton Public Library.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 21

11.05.2020

(22) Louis Wain, popular Edwardian illustrator of children’s books whose drawings underwent a notable transformation during his periods of schizophrenia. Sequences of his drawings have been reproduced frequently recently in Observer colour magazine and IT amongst other places.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 22

(23) Aleyse, one of the mental patients whose painting is reproduced and discussed in “THOUGH THIS BE MADNESS”: Thames and Hudson 1961.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 23

15.05.2020

(24) See “THE DIARY OF VASLAV Nijinsky [sic]”, Panther 1966.

PDF: JN FOOT NOTE 24

25.04.2021

(25) See “CENTURIES OF MEDITATIONS” by Thomas Traherne.

Thomas Traherne, CCEL, 1960 – Devotional literature – 228 pages

Common terms and phrases:

able admire affections ages amiable Angels appear beauty become beloved benefit better blessed blessedness body cause Christ communion consider contemplate created creatures darkness delightful desire Divine doth endless enjoy enjoyment esteem Eternity everlasting excellent expressed eyes Father Felicity fountain give glorious glory God’s gold greater greatest happiness hast hath heart Heaven and Earth Holy honour Image infinite Jesus joys King Kingdom knowledge laws light Line live Lord manifest manner means mind miserable nature never object ourselves perfect person pleased pleasure possible praises precious prepared present principles prize Psalm reason receive rejoice riches righteous satisfiedSaviour seen sense serve shine soul space Spirit stars sufferings sweet Temple Thee things Thou thought Throne treasures true understanding unless unto virtue wants wherein whole world wholly wisdom wise wonder

5.01.2024

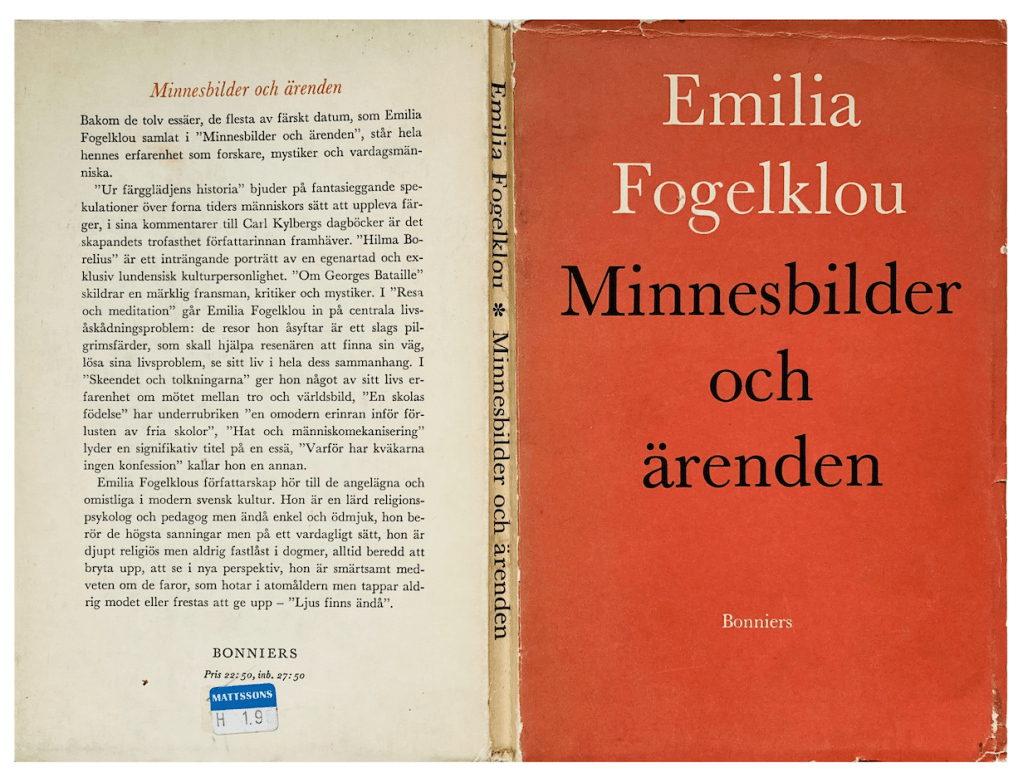

Emilia Fogelklou: ‘About Georges Bataille. Mystic and Critic’ 1963

By way of introduction, Petra Carlsson writes:

“…in Sweden there was a group of women writers and thinkers called Fogelstadgruppen [Fogelstadgruppen, an informal constellation of politically and culturally engaged women interested in societal change in the left-liberal direction.] who brought the spirituality of Bataille and Kandinsky into the center of the women’s movement. In the course of time, these influences were to help establish Sweden as a pioneering country with regard to equality between men and women in church life as well as in society. One of the group’s key voices, theologian and writer Emilia Fogelklou, was explicitly guided by Bataille toward a new account of Christian theology and spirituality and of ethics and societal formation.” [1]

“In 1963, the year after the death of the radical writer and eroticist Georges Bataille, Fogelklou wrote an essay on Bataille. (She writes the same year as the French philosopher Michel Foucault writes his essay on Bataille, “Préface à la transgression”, which can be read in parallel with Fogelklous.) Fogelklou thus writes an essay on the scandalous Bataille, which has then become everything more important to her thinking. Her essay is an introduction to his writing as a deep spiritual writing, but is thus also an introduction to Fogelklou himself. In the article, Fogelklou claims that if one as an individual strives away from oneself as a stable subject through continuous transgression of what appears to be impossible and forbidden, one can achieve a kind of diversity of the present and presence. By constantly violating the boundaries you do not think you can cross, you can meet the potential and unforeseen force that is hidden in what appears to be static. It is thus about a kind of artistic viewing and transcendence.

“With this insight in her luggage, Emilia Fogelklou, 84 years old, travels to a parish home in Härnösand to lecture about Bataille and his constant transgression as a spiritual approach for the people of Härnösand. “It’s not just Stockholm that needs new ideas,” she says.

“With the help of thinkers such as Bergson and Bataille, Fogelklou makes up for a dualistic opposite thinking. As long as we adopt a logic in which the world is divided into that which is present and that which is absent, that which is immanent and that which is transcendent, the difference between the one and the other will always appear as actual and absolute. Dualism will be taken for granted, and thus the distance between people will also persist. Empathy and compassion will be limited. But, says Fogelklou, this formal separation can be broken through, it can be exceeded by an inner force. The division between shell and core, of us and them, me and you, spiritually and secularly, can be transcended by an inner immanent force that is beyond the reach of simple divisions between the one and the other.” [2]

“In 1971 in Tunis, Michel Foucault held a series of lectures on the French painter Edouard Manet. One of Foucault’s sources of inspiration, Georges Bataille, had published a book on Manet in 1955, the same year Foucault left Paris for Uppsala where he arranged discussions on Manet in his home. One can sense Bataille’s presence in Foucault’s lectures over a decade later. As is often the case, Bataille’s indirect presence enhances the aspect of theological or spiritual negotiation taking place in Foucault’s work.” [3]

Refs:

1. Petra Carlsson: ‘Foucault, Art, and Radical Theology: The Mystery of Things’, Routledge, 2019

2. Petra Carlsson: ‘To see the world beyond categories’ [Att åskåda världen bortom kategorier], Tidskriften Evangelium, Issue 5, October 2013

3. Petra Carlsson: ‘Foucault, Manet and New Materialist Theology’, in ‘Literature and Theology’, Vol. 30, December 2016.

Emilia Fogelklou: ‘About Georges Bataille. Mystic and Critic’ 1963

‘Memories and cases’ [‘Minnesbilder och ärenden’], Bonniers, Stockholm, 1963, pp113-130

[113]

The first time I encountered the name Georges Bataille was in ‘Gaëtan Picon’s Panorama de la nouvelle littérature française’ (1949). It was under the heading “From sociology to mysticism”. Of his writing, L’expérience intérieure and the journal CRITIQUE were mentioned. The art history volumes on the Lascaux cave and Manet had not yet been published (Skira, Geneva).1

“He is unique in suffering through spiritual problems, as one would otherwise suffer through bodily pains,” it says. “He is his experience. — He seeks the source.” — Sartre calls him “a new mystic”.

I had no idea, when I (through the Västerås diocesan library) was allowed to borrow “L’expérience intérieure”, that this was the only copy in any public library in

1. Under the heading: Summa atheologique, the three books are listed later: inner experience, the guilty, Nietzsche Another early book, Haine de la poésie, is included in the new edition, l’Impossible (1962).

8 Fogelklou

[114]

Sweden (Gbgs stadsbibl.) [Gothenburg City Library]. Only after the author’s death (July 1962) was I able to get hold of some data and contemporary judgments (Bengt Holmqvist in D.N. 9/7, Michel Bernard in l’Art 24/7 1962).

After brilliant studies, Bataille had obtained employment at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. He was among the early surrealists and was for a period a “democratic communist”. He belongs to those who most deeply realised the degradation of man and the human, which the Second World War made evident. It was in his 40s that his actual writing began with L’expérience intérieure (1943). Pulmonary tuberculosis had then forced him to leave his library position.

“Poet, mystic, philosopher, critic, deeply aware of man, his brokenness in an age that coldly enslaves him and where war itself has become a kind of watered-down scientific activity,” says Michel Bernard. — “Scandalously little known”, he adds. “Bataille was not suitable for the half-sleep of the novel-gluttons, because what they long for in advance is an even deeper sleep.”

Bengt Holmqvist calls him “a mystic of sex and death, possessed by the powers of creation and destruction, which our generation has such difficulty seeing in the eyes”.

Even though he was from France, it has been difficult to, through Copenhagen Library, to find some of the Bataille’s

[115]

books, several of which were out of date. The work La part maudite (The Fate of the Curse) with the somewhat paradoxical subtitle Économie Génerale fortunately in the Riksdag Library [Stockholm]. Through the bookstore I managed to get a novel, Le bleu du Ciel, Le coupable (diary, before the breakthrough) and La littérature et le Mal, a volume of essays from his valued journal. (I have not been able to get the book about Nietzsche.)

I return to the book about his inner experience, which had piqued my interest from the beginning. It is quite hard to read. “It is with sense and will that he writes chaotically,” says one of his critics. Bataille knows that only the dimensions of silence, “a presence that only the heart understands”, can reflect his mystical experience. Nevertheless, from his blazing certainty, he has to try to make himself known. It is difficult for this hyper-intellectual to de-philosophise and de-theologise himself. Out of fidelity to reality, he allows contradictions to take place.

I state: “By inner experience I mean what is usually called mystical experience, in a state of ecstasy, rapture or at least meditative rapture. I am thinking less of confessionally formulated experience, where at least until now one has felt bound by a certain confessional boundary. Therefore, it invites me against using the word mystic or that

[116]

to express myself in too narrow terms.1 The inner experience responds to the necessity in which I find myself: the whole of human existence from my point of view. The same kind of experience works within confessional religion,” he emphasises. “But dogmatic basic assumptions give undue limits. He who knows everything in advance cannot cross a familiar horizon line.”

Bataille later mentions his book on “The inner experience”: “a book out of despair”. “He who does not die of being human, never becomes human.” Like Sartre, he believes that life as a human being begins only beyond despair. He does not give any private reasons for despair in this work. In “Le Coupable,” whose diary entries were mostly written before the breakthrough, although it was published afterward, his “terrible (affreux) childhood” is mentioned once, also that his father was blind. It also shows how the during relocation within an occupied France looked into the war suffering of those involuntarily dragged along, of children, women, men, the elderly. “The

1 Cf. Hj. Sundén: “If the religious experience is given greater importance than the religious doctrine, for us Christians many worrying questions will be silenced.” (Man and religion p. 94.)

Paul Tillich: religious faith = “the state of being ultimately concerned” — a seriousness that was characteristic of G. Bataille.

[117]

one who now looks into the misery of the masses,” he says, “should be able to come with the simplicity of the gospel and the directness of tears. The anxiety should give his words transparency. For my part, I say everything as directly as I can, although then I am shaken by bitter irony. It is impossible for me to be more than anyone else. It is not [a] proclamation that I have. It is a secret, a renunciation of oneself,” he says (in Coupable). “We want to find what we seek, which is only to be freed from ourselves.”

Man’s notions of glory (gloire) or prestige are the worst thing about him. Caesar’s words about being the first in one’s small town rather than the second in Rome reveal precisely the most miserable thing: everything seems like nothing, unless there is someone one surpasses oneself. This in current protest against wartime gloire-talk, in all its endless horror. Bataille sees how those who stand there in the middle of the activity are put to sleep by it. “It can no longer be allowed to continue like this. I am the first to perceive man’s disgust for himself. Spiritual experience awakens.”

“All our life is burdened with death. — But in me this definitive death itself has the meaning of rare victory. It bathes me in its light. It opens within me an infinite bright smile: I may disappear. I do not imagine the world as a bounded and closed essence, but rather like that which is passed from one to the other, when we smile or when we

118

love.” (Cf. Martin Buber’s The Between, the living relationship.)

The human feeling of powerlessness breeds anxiety. Anxiety cannot be unlearned. But what do we do with it? Instead of getting to the bottom of one’s anxiety, one anxiously babbles on and escapes in various ways. Someone can, through anxiety, be called to the measure of their premonitions. This might just have been his chance. But what a mess it becomes inside the one who turns away: he suffers just as much, becomes stupid, false, superficial. It is necessary to remain, straight and motionless in dark solitude. (He testifies about his own avoidances in Le Coupable.)

“You god of despair, who crucified your son, give me your heart. My despair is nothing compared to what God must be. — But still. — — To me, idiot, God speaks out of the darkness with a voice of fire. You don’t understand the darkness in a soul stripped bare. I cry to heaven: I understand nothing.” Death is closely connected with his inner experience. (A Swede thinks of Gullberg’s lines: “Send over me a whirlwind that shatters the shape of my being”. Other things remind me of Pär Lagerkvist. I also think of a passage in Lars Gustafsson’s debut book, Bröderna (s. 47 ff) : “What happened? That’s just what I don’t really know. For a large part of my life I’ve thought about it almost daily. I think it means a lot, but I really don’t know

[119]

what it really was. Nowadays I am inclined to say that it cannot be known.”[)]

His defining experience of “what is”, becomes what G. B. then constantly inquires into, even as he states kinship with artistic inspiration, smiling, intoxication. “After this, I cannot have any other value or authority.” But when it comes to communicating experiences without borrowing Christian words, it becomes difficult. — He distances himself from philosophy. When Cartesius [Descartes] explains: I think, therefore I am, then he completely ignores the intuition that makes someone start to think for themselves at all! With Hegel, life is drowned in pure knowing (something that B. dwells on in several places). In the mind, as in the eye, there is a blind spot. Life eventually reveals this blind spot. Saints succeed best in their rendering, he says, they know with their hearts and live in the life of prayer. Our lack of ecstatic knowing is a loss. The one he lets speak the most is Angela of Foligno. But Master Eckhart and John of the Cross are also mentioned. Where some mystic marks the inability to reproduce such experience in words, Bataille recognises himself best: the inner experience has the peculiarity that, in the face of it, our negative expressions become truer than the repetition of traditional words. “I cry to heaven: I know nothing. But in rare moments I have touched the utmost.” “In the beginning, the traditional

[120]

regulations are the obvious starting point: they are wonderful . . . I am not ignorant of Christian exercises: they are in the most authentic way dramatic. But they lack a first movement (originality), without which the exposition remains subordinate.

Rare Christians have, from the sphere of speaking, reached into ecstasy, the mystical experience, despite a characteristic predilection for the discursive.”

B. distances himself from the asceticism of the mystics. “It does detach from things, but can kill connections with other subjects.” The whole of unmutilated humanity applies to it. Real asceticism is total simplicity, immediacy.

To have existence, to truly “be somebody”, cannot be attributed to a subject who isolates himself from the world but instead to one who becomes a point of communication for belonging.

When “The Inner Experience” came out in a new edition after ten years, it received a preface that criticises his book.

He had there “wanted to say everything at once”. However, it is not the boldness that displeases him. “But I hate its long-windedness and obscurity.” He has already called his style of presentation a “violent thinking”, (“high tension intellectuality” says Bengt Holmqvist). And probably it has an intensity and a seriousness that compels the reader

[121]

to stop and ponder. “Truth has rights over us. She has even all rights” (l’Impossible).

Despite the warning about an activity that without conscious criticism leads us into events that give “disgust to man”, B’s own life after the end of the war becomes a new, rich working time. Bengt Holmqvist writes: “The silent librarian on the fringes of Surrealism” became “a writer with rich and versatile productivity and a cultural critic with growing influence.”

La part maudite (1949) emphasises that the most important thing for the post-War era is not to further develop the forces of production, but to give, to share with the rest of the world. The general public demands that the predominant interest in acquisition be replaced in testing our expenditure types. B. sets the sacrifice in all its forms (even the most primitive) in opposition to our worship of work and tools. (He substantiates the slogan with sociological sections on partially new research on the nature of the victims — in Aztecs, Tibetans, in Islam, etc.). “Man searches in all myths and rites for an intimacy with life, which has been lost to us.”

B. references Max Weber’s views on industrialism (in connection with reformed religion) and quotes Benjamin Franklin’s words: [“Five Shillings turn’d, is Six: Turn’d again, ’tis Seven and Three Pence; and so on ’til it becomes an Hundred Pound.”] Nothing could stand in more cynical contrast

[122]

to sacrifice in a religious sense, according to Bataille. It is the commodity that reveals the rule of the thing, with the reification of the human and fellow human as well. “Where we could have reached the Grail, we settle for the bowl” (literally: “the cauldron”).

It became too detailed to go into B’s abundant comparative material. In the Marshall Plan, he suddenly meets his joy. (When B. wrote, it was a theory, which we now see working its way into practice with different problems than what could have been expected at the time.)1

I will not go into more detail about the art history volumes about Lascaux and Manet. The former is directly descriptive, but exudes rapture over the originality, directness of the cave paintings. They convey “the longing for the miraculous, in art as in passion, life’s deepest expectation”.

The monograph on Manet, in depicting the artistically new indifference to the “subject” — in contrast to the play of the sun and days around the phenomena — provides a certain parallel to Bataille’s own way of depicting inner experience.

Regarding Bataille’s “fictional” production, novels and poems, written before the breakthrough, but published much later, “at the request of friends”, I would like to give only brief mentions: “Le bleu du ciel” (printed in 1937), (as Michel Bernard calls

- Cf. Jonas Nordenson, Technology and freedom, D.N. 9/1 1963, together with Ulf Brandell, Keynes’ predictions in the same issue.

[123]

it “one of the most beautiful and purest novels”) and “L’abbé C” [sic]. In the preface to the former, the author writes: “Since 1936 I had decided not to think about it. The Spanish War and the World War made it meaningless. And I am now far from the state of mind from which the book emerged.” (I cannot share Bernard’s high estimation, but I ask: had the prestige-hater Bataille discovered his fellow man in the prostitutes early on — through all the humiliating details, which without embellishment were raised in the day? He reveals in some cases a marked tenderness, compassion. In the novel “l’ Abbé C” [sic] it is more of a psychological drama.)

About himself, Bataille says — in Le Coupable — “I want life to undress in me. I have lived without hiding anything. In me everything is violently damaged and cursed.” From L’impossible it was already stated: “Truth has rights over us. It even has all rights.” Bataille has “found the links of eroticism to be of a perishable nature, whoever the creature is with whom we have tied such links”. — — — “I say ‘love for the possible and the impossible, not for the woman.’ — — “Love — it is longing for an object of total desire.”

“Eroticism is cruel, leads to misery, requires ruinous expenses,” said Le Coupable. In other places, Bataille dwells on the mystery of nudity as an endless humiliation of human beings.

[124]

But in erotica, Bataille also sought a momentary liberation from the self with all its anxiety, yes, the death of the self, “a small death”. The most significant is that of communication. Real communication presupposes the encounter with some perceived lack: “like death, it happens through the crack in the armour. It requires the encounter between two wounds, my own and another’s. — — — The crucifixion is, after all, the blessing through which the believer is able to approach God.”

In his work L’Érotisme, written during pressing times of illness, he seeks to find the connection between erotic and religious life in all its different species, an investigation that seems to him of the greatest importance for our whole life. In the preface to this work (which probably never turned out to be what he hoped for), he enumerates all the many people who assisted him, including the procurer of photographs (although these give a misleading idea of the nature of the book upon superficial browsing). He has “been suspected of dubious intentions, which was very unfair” (Bengt Holmqvist).

In vain, one looks in Bataille for traces of the experience of love, where someone placed his life “in the hands of the only person in the world in whom his soul could find peace” (Poul Bjerre).

Bataille speaks warmly of friendship. (That’s what he learned from Nietzsche.) I find no trace of any maternal, sisterly or equal female essence in the memory images that sometimes appear today

[125]

in the diary entries in Le Coupable. He gives from his “terrible” childhood two different images of his father, none of his mother. “My blind father with hollowed-out eye sockets, long skinny bird’s nose, wailing cries, long silent smiles. I would like to be like him,” he continues. “I can never help asking questions of the darkness, and I shudder at the thought of having had before my eyes this anguished involuntary ascetic throughout my childhood.” But in the vigilance for grief in all its expressions, which characterises Bataille, he has seen even this blind man “with raised arms and wide-open eyes, while he stands and looks straight into the sun and himself from within becomes light”.

Despite the absence in the authorship of equal women, one notices not only the preference for Angela of Foligno as a mystic, but also his — one is almost tempted to say identification — with Emily Brontë in the first basic essay in La littérature et le Mal (1957).

Bataille’s conception of communication (in the real sense) gives his literature review its particular focus. In La littérature et le Mal we encounter it in different ways when treating different authors. Among the non-French, I mention, apart from Emily Brontë (who in the essay also gets her biography), Kafka and William Blake. The French writers he

[126]

includes in this selection of own articles (from Critique) are: Baudelaire, Michelet, Sade, Proust and Genet.

Le mal, evil, shall be redeemed, not condemned. We have solidarity with the wicked. Our privileged clumsiness exacerbates the evil. Real literature must see like the child the impenetrable simplicity of all that is. It must be reflected in seeing eyes, without idealisation or condemnation. The good is usually identified with submission and obedience. But freedom always keeps some path open, where the good has put a lock. In the essay on Michelet, B. emphasises that the “le Mal” of the title does not refer to the evil that abuses its strength at the expense of the weak, but instead to the evil that goes against one’s own interest and presupposes a foolish desire for freedom. It concerns a pointed form of evil, which does not mean distancing oneself from morality, but a step towards deeper morality.

In the last essay on Jean Genet, this is highlighted very sharply. Despite the great importance Genet’s Journal du voleur etc. has from several points of view (psychological, social, etc.), Bataille — in some opposition to Sartre — does not count it as literature. Genet exalts himself above his crime and is locked in it in a kind of desire for superiority. It does not involve real communication.

Perhaps the strongest contrast to Genet is the interpretation of Kafka, the most interesting in my opinion

[127]

the essay. I am most critical of his essay on Blake, however unnatural it would have been for “the Bataille of inner experience” to avoid a confrontation with this prophet and mystic. — The opening essay on Wuthering Heights lingers longer than any of the others by Emily Brontë herself, who in her untouched ethical purity, however, expresses such deep experience of the abyss of evil. The author recalls how early she lost her mother, how the desolation of the heath and the dry severity of her father isolated her short life, while the heated anxiety of literary creation filled her own world and that of her sisters. She, the quietest of them, broke her silence only when she wrote, Bataille calls Wuthering Heights “one of the most beautiful books of all time”.

He refers to it more extensively than any other, with particular regard to the rare bond, which — without infidelity in the heroine’s marriage — connects her forever with the novel’s culprit, Heathcliff, the childhood friend from the heath, who becomes the cause of her own death. His evil had begun as a child’s response to his bitter life experience, a defiance that was also directed against the good.

How could the inexperienced Emily be able to portray this? Bataille asks himself. He cites some of her poems, but does not believe that on the basis of them it can be claimed that Emily had a direct mystical experience. But she promotes a new view of evil.

[128]

Not the kind that exploits others for profit, but the evil as a response to the incomprehensible injustice of someone’s existence. The essay on Emily Brontë ends with a section entitled “Literature, Freedom and the Mystical Experience”. Throughout the book, one is warned about this connected perspective.

“We cannot doubt the fundamental unity of all those movements, where we escape interest calculations and experience the intensity of a now . . . Contemplation, free from reasoning, acquires the same simplicity as a child’s smile.”

“There is,” Bataille quotes from the Surrealist Manifesto, “a certain point in the soul from which life and death, the real and the imagined, the past and the future, cease to be inexorable opposites.” And “I add”, continues Bataille: “also the evil and the good, the pain and the joy. This point is felt both in dynamic (violent) literature and in the power of mystical experience. The way there matters less: it is the point alone that is the important thing.”

What George Bataille writes is born of sadness, with death in sight. Without an understanding of “L’expérience intérieure” he is difficult to approach. It seems to me to be his most important contribution. He looks at life, at religious experience and literature from different viewpoints than the generally accepted or group-shared. His language

[129]

is imageless, his poems mostly unpleasant. His utterances can have stinging sharpness. They can also — after voluntary, sometimes [be] long-winded, stripping away of intellectualistic, art-wise or religiously historically formulated expressions — leave the reader with a certain sense of loss. He does not interpret the mysterious event, but out of all his certainty of conviction he states its existence. At some point he simply cannot dispense with the inherited religious language, despite the asceticism he imposes on himself on that point; he wants to assert his poverty by using only the words to which he is entitled. Similes and images are not for him. He is not a poet. And although he has written several pages in praise of the spirit of play — he knows its kinship with inner experience — that spirit is missing in his own way of writing. He knows himself to be “child of a cursed time”. And from that background — “la part maudite” [“the cursed part”] — his message gets its shocking seriousness.

But for French people with distinct formal requirements, Bataille becomes difficult to define. Even his friend and admirer Michel Bernard captioned his obituary: La folle chevauchée de G. B.

In the Dictionnaire des auteurs français (1961) the final verdict on Bataille is given: “— — through his taste for extreme experiences, through his knowledge of intoxication and through the deliberately chaotic nature of his writing style, he belongs to the genre

9 Fogelklou

[130]

of writers which seems to write only to earn the silence.”

As a complement to this scornful view, which derives its ironic point from Bataille’s own view of silence, I still want to recall on his behalf a few lines from Paul La Cour’s Fragment af en Dagbog:

“When your ambition is defoliated, the tree of your will overturned, you wake up one day alone with yourself and are sincere.

Sincerity does not require Courage. It does not have fearless eyes. It is Childhood before Anxiety.

Now you can talk. Your smallest word is a poem.”

[e n d]

trans. David Patten, January 2024