[29.12.2024 – 31.01.2025]

“…we are in a reality which offers us meanings, a horizon of meanings which arrive after the destruction of the market that the sublime has permitted us.”

– Antonio Negri: ‘Letter to Manfredo on Collective Work’ in ‘Art et multitude’, Polity Press, 2011, 39

“…the perfection of an art lies in its being simplified as much as possible, the painting of the visual appearance of objects, considerably purified by their conception, will be the source of works of art with a much loftier tone. / The beautiful must be, in Kant’s excellent expression, a “purposiveness without purpose”; that is, it must require an internal harmony without an external goal. It must be distinguished from seemliness, which is only the arrangement with a goal in mind; and it is not necessary to have the definition of a beautiful form for it to be pleasing.

– Maurice Raynal: ‘Conception et vision’, Gil Bias, 29 August 1912

Still-life engages the painter (and also the observer who can sur mount the habit of casual perception) in a steady looking that dis closes new and elusive aspects of the stable object. At first common place in appearance, it may become in the course of that contemplation a mystery, a source of metaphysical wonder. Completely secular and stripped of all conventional symbolism, the still-life object, as the meeting-point of boundless forces of atmosphere and light, may evoke a mystical mood like Jakob Boehme’s illumination through the glint on a metal ewer.

– Meyer Schapiro: ‘The Apples of Cezanne: An Essay on the Meaning of Still-Life’, 1968, in ‘Modern Art 19th & 20th Centuries, Selected Papers’, George Brazil1er, Inc, 1978, p20

— — —

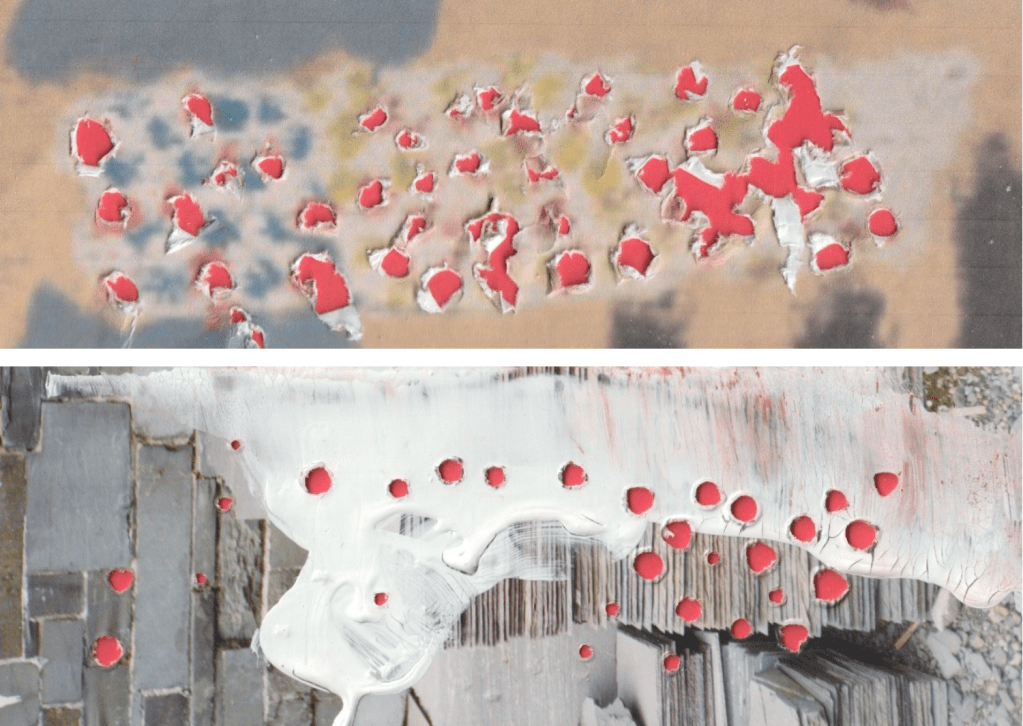

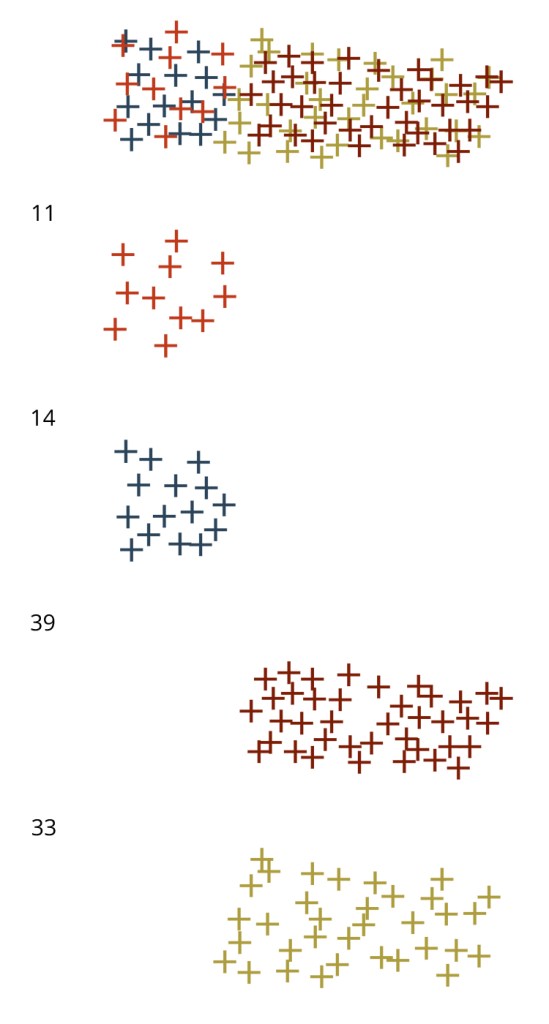

23.01.2025 | 34 Drilled Holes

Antonio Negri: ‘Art et multitude’, Polity Press, 2011

Letter to Manfredo on Collective Work

The spectacle of the world is its continual reproduction. Here, when we are inside this movement, the collective dimension and the dimension of production become one and the same. We succeed in placing ourselves at the level of value when we produce — that is, when our productive tension realizes itself through collectivity (otherwise it would not realize itself). Engaging oneself in the act of production this is the eminent form of speaking out. There is no production without collectivity. There are no words without language. There is no art without production and without language. Art is, above all, this synthesis. Art is the construction of a new language which, first, alludes to a new being; then, when art explodes and the synthesis of language with the new is effected — a new element of life and of knowledge — another dimension of ethics has become real. We are Spinozans out and out — we see being as constructing itself through the action of desire, as a continuation of appetitus, of conatus, of the pleasure of living. As a will [40]

to potenza. Art is conspicuously the first, but also the fullest and most beautiful of the configurations of this extraordinary movement. Starting from deconstruction, our work turns, then, towards a collective process of self-valorization, of creating circuits of value and signification that are entirely autonomous, free from the market and definitively aware of the independence of desire. [41]

[. . .]

Art, we said, lives by production. Production lives by the collective. The collective constructs itself in abstraction — today this collective and productive abstraction is seeking to find itself as a subject. This is what communism is. We are on the edge of a history which has almost arrived at its conclusion — on a wave which, even though it swells and looks imposing, will nevertheless become gentle as it approaches the beach. Although there is still nothing to indicate that we shall reach safety, we know, even more than Columbus, on the basis of debris and of the far-off intuitions of life, that we are about to succeed. Art anticipates and follows; its ambiguity goes hand in hand with its humanity. [43]

(Primary Title)

When more than one title has been reported for a painting, the catalog adopts as the primary title the one assigned by the artist, and lists all other titles as alternates—even when the artist appears to have mistitled the painting and one of the alternate titles would be a more accurate description of the subject matter.

– Frederick Ferdinand Schafer Painting Catalog, Conventions: Title components of a painting description

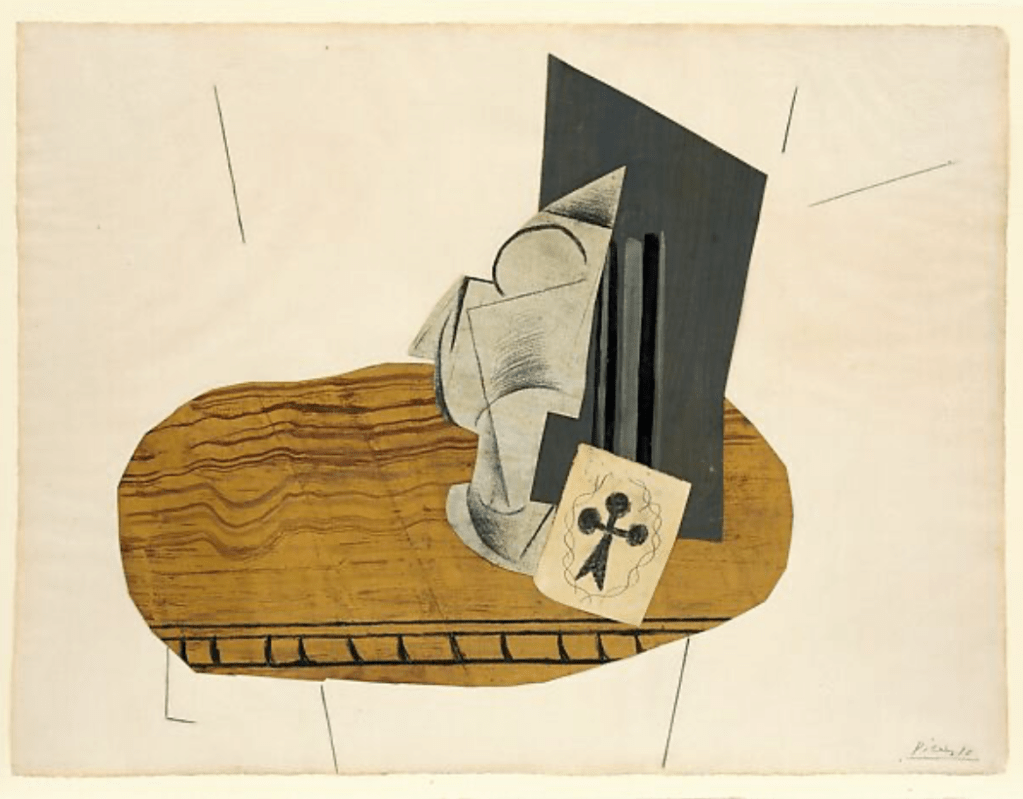

Pablo Picasso: ‘Still Life (Wineglass and Newspaper)-(Primary-Title)-(47.10.83)’, ca. 1913-14, oil and sand on canvas, The T. Catesby Jones Collection, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts [seen 3 October 2024]

“…and a white strip of stippled colours suggesting the sparkle of reflected light.”

– Virginia Museum of Fine Arts / Object Number: 47.10.83

“The poem is a constructed thing, [LINK] and not a jeweller’s display window. [. . .] A work of art exists in its own right and not through confrontations with reality.”

– Max Jacob, Preface to ‘La coupe aux dés’, 1916

[image removed 27.02.2025] 13.01.2025: acrylic, conté crayon dust and teabag stain on tape and plan

17.01.2025 | ‘the red dots’, acrylic, conté crayon dust and drilled holes on early 1990s photograph taken at Dinorwig Slate Quarry, North Wales

18.01.2025 | 13.05cm

“It is also possible that Picasso’s ironic play with pointillist dots, which emerged as a major pictorial device early in 1914, functioned in part as an answer to the presence of Carra and Soffici in Paris at this time and to the continuing importance of Divisionism in Italian aesthetics.”

– Christine Poggi: ‘In Defiance of Painting : Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage’, Yale University, 1992

‘Green Still Life’, oil on canvas, Avignon, summer 1914, MoMA, New York

The omnipresent green of this picture establishes a lyrical mood and provides a continuous foil against which the staccato accents of other hues are played off. Pointillist stippling, which Picasso had been using sparingly for over a year to differentiate a plane or indicate a bit of shadow, is employed more generously here, its dots given special brightness by the use of commercial enamels.

– William Rubin: ‘Picasso in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art’, Feb. 3-Apr. 2, 1972

…multi-sensorial phenomena: radiance, liquescence, fragrance, reverberation / liveliness is performed / liveliness stems from the installation / “liveliness” / liveliness, stemming from the changing appearance of materials / to speak silently / liveliness becomes manifested as a phenomenon of sparkling, reflecting eyes / inspiriting is a process…encoded in the glittering materials…as a temporal phenomenon / — liveliness is performed — / liveliness stems from the installation.

– Bissera V. Pentcheva: ‘Glittering Eyes: Animation in the Byzantine Eikōn and the Western Imago’, Codex Aquilarensis 32, 2016

Sketchbook #09: detailing Rev John Homes observation that, “it seemed as if God had created man only for making buttons.”

Sketchbook #18: detailing the petition of the starving button makers in June 1791.

Ashtavakra Gita | Pearl

2.8

I am not other than Light.

The universe manifests at my glance.

2.9

The mirage of universe appears in me

as silver appears in mother-of-pearl… [how the universe appears to exist, but does not]

…nothing counted but the instant alone, I escaped the common rules / instant to the instant, the ecstatic to the ecstatic / which has the immediate as its object, the heir of theology / the almighty of the instant, this is the amok, this is the height of powerless / instant guides me / opens itself up while denying that which limits separate beings, the instant alone is the sovereign being / no longer reducible to discourse / Nothing in the instant is knowable. In the instant, there is no longer any ego possessing consciousness because the ego that is conscious of himself kills the instant by dressing it in a false costume, that of the future that this ego is. / I am talking about the instant, and I know that the instant brings about in me the passage from the known to the unknown. Insofar as I envision the instant, obscurely, the unknown touches me, the known dissipates within me.

– Georges Bataille: ‘Méthode de méditation’, Gallimard 1973 / trans Michael Tweed 1998/2002, https://pensum.ca/ [accessed 21.12.2014]

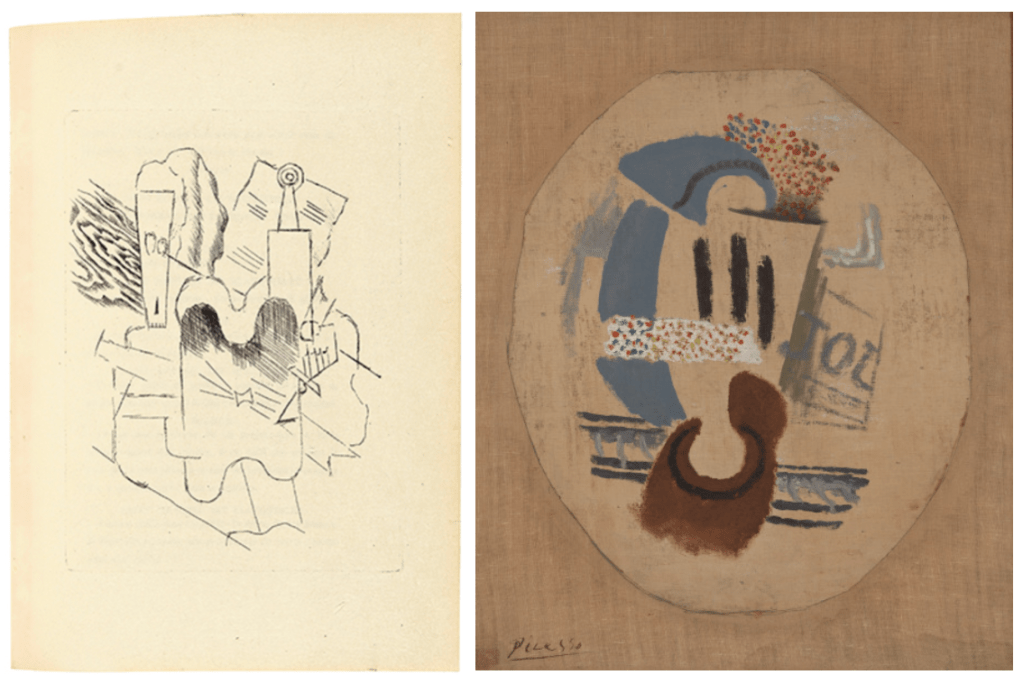

[left to right]

‘Glass, Newspaper and Dice’, 1914 / Museo Picasso, Málaga

‘Glass and Dice’, 1914 / [Zervos II/2, no. 773, p58]

‘Glass of Absinthe’, Spring 1914 (1 of 6) / MoMA, New York

“… perspectival representation, coming forward from the picture surface. Douglas Cooper, in the catalogue to the exhibition, ‘The Essential Cubism 1907-1920’, wrote nearly 11 years ago, ‘Picasso carefully placed the forms one to the next not so much to record accurately the visual scene before him, but instead to create a tapestry-like composition in which the surface pattern counts as much as or more than the depicted scene. But despite Picasso’s increased concern for respecting the surface of the canvas, it is important to note that he is still representing solids and masses much as a sculptor would: there is no evidence here of the “painterliness” of Braque’s contemporary Cubist work’.”

– Art Monthly, April 1994 | No 175

“Evenness and openness did seem to mean better painting — had not that been Braque’s essential proposal to Picasso for the preceding three years? — but they also meant empyting, reducing, diagrammatizing, blanking out.”

– T. J. Clark: ’Cubism and Collectivity’ in ‘Farewell to an Idea, Episodes from a History of Modernism’, Yale University Press, 1999, p192

‘Glass and Ace of Clubs’, papier collé, 1914, The Met, New York

‘Glass’, painted tinplate, nails, and wood, 1914, [tbc]

‘Bottle of Bass, Glass, and Newspaper‘, painted tin plate, sand, iron, wire, and paper, 1914, Musée Picasso, Paris.

Picasso’s ‘Bottle of Bass, Glass, and Newspaper’ (1914) / seminal example of his Cubist sculptural practice, marking a pivotal shift in modern art / innovative use of materials, form, and space.

Medium and Materials (painted tin plate, iron, wire, paper, sand)

• non-traditional, everyday, and industrial materials—radically different from classical marble or bronze.

• use of tin and wire = lightweight, malleable structure, appropriate for layered, assembled composition.

• sand and paint = surface treatments = illusionistic depth (trompe l’oeil).

• integrates visual and material languages.

Aesthetics of assemblage—a proto-installation practice / blurs the line between sculpture and painting, object and image.

Form and Composition

• built up from intersecting planes and curved surfaces = Cubist pictorial language of fragmentation and simultaneity.

• a cylindrical form (representing a bottle) rises vertically, central to the composition.

• adjacent flat cut-out shapes suggest a glass and folded newspaper, using silhouette and contour rather than full volumetric modeling.

• each side of the sculpture offers a different composition = multiperspectivalism.

• construction and collage techniques = the three-dimensional equivalent of papiers collés.

Color and Surface

• painted in muted greys, browns, and blacks + occasional trompe-l’oeil effects (text, shadows, and faux textures / printed newspaper, label of the “Bass” bottle).

• painted chromatically =o simulate materiality (like glass sheen or newspaper print).

• added sand = gritty, physical texture to some surfaces, enhancing material contrast and optical complexity.

• interplay between illusion and material truth.

Construction and Assembly

• assembled rather than modeled, built from cut, bent, folded, and wired components.

• forms are flat but suggest volume / overlapping and shading / three-dimensional collage.

• use of wire and tabs reveals the mechanics of construction, highlighting a raw, almost industrial aesthetic.

• transparency of method = the way it is made = meta-pictorial awareness = a work of art’s self-consciousness about its own status as a representation / calls attention to the fact that it is a picture (or image), not reality / an object and a commentary on image-making / the idea of representation itself

Spatial Dynamics

• not fully volumetric / volume through strategic flattening and layering.

• negative space = critical = gaps = complete forms mentally.

• to be viewed in the round / unfolds sequentially, like walking around a collage / shifting viewpoints; collapses frontality and depth.

— — —

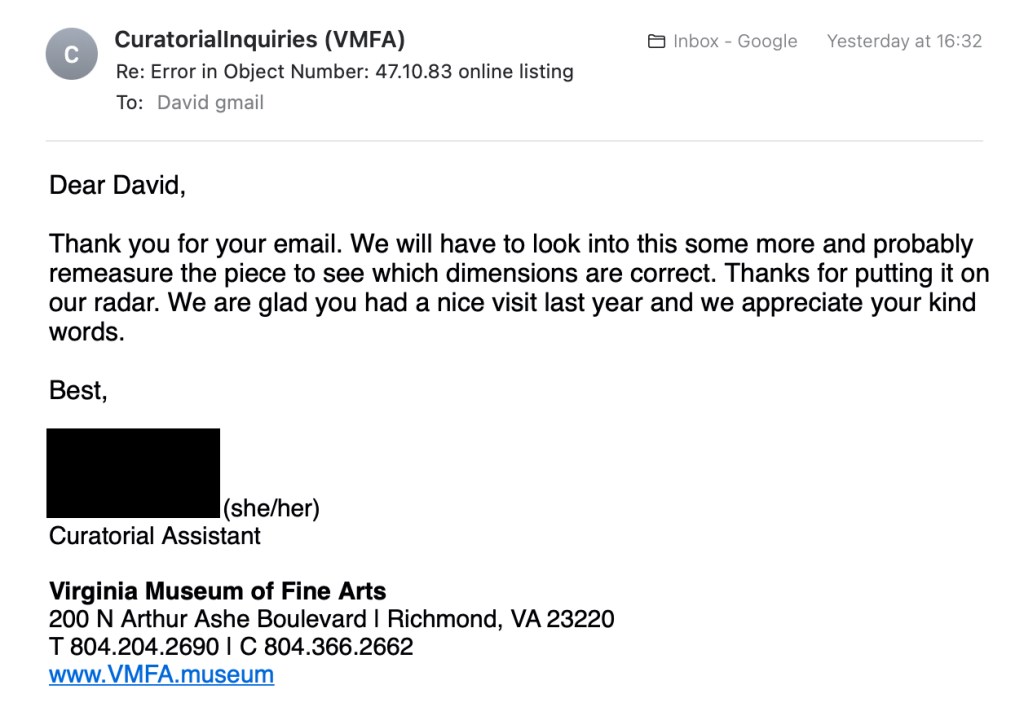

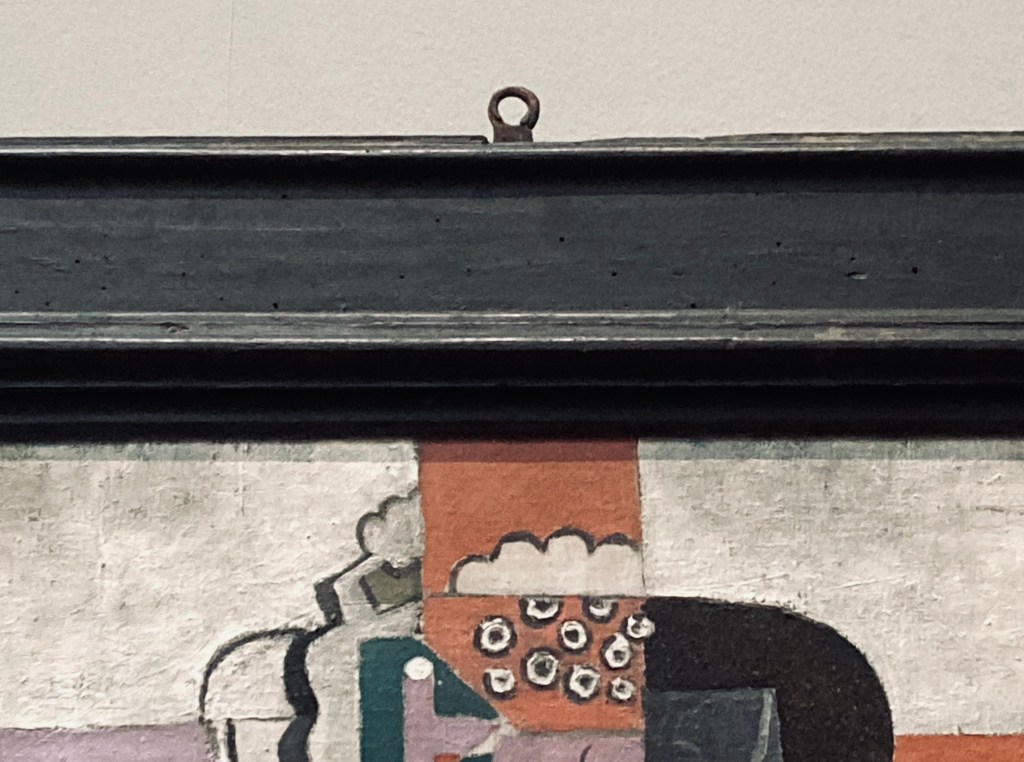

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, USA, 3 October 2024

Pablo Picasso: ‘Still Life (Wineglass and Newspaper) (Primary Title)‘

Date: ca. 1913–14

Medium: Oil and sand on canvas

Collection: Modern and Contemporary Art

Dimensions: Unframed: 52.4 x 43.8 cm

Object Number: 47.10.83

Location: G153 – Deane and Goodwin Galleries

In 1914, Picasso explored the use of words and the expressive and conceptual possibilities of reflected light and vivid color in Cubist painting. At the center of this still life is a fluted goblet defined by a gray-blue patch of paint at its edge and by a white strip stippled with colors suggesting the sparkle of reflected light. A second area of dotted color above the glass creates a background wallpaper pattern. At the right is a fragment of folded newspaper, with the first three letters of the word “journal” visible. The straight but broken line of a decorated table edge, covered by the brown shadow of the goblet, marks the bottom of the arrangement. Picasso painted the image on a piece of canvas that was cut into a rough oval. He affixed it to a rectangular canvas with a more open weave, producing the effect of a frame within a frame—or an oval picture hung on a wall.

Exhibition History:

‘Salute to Spain’, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, March 19 – April 4, 1971

Provenance:

(Galerie Kahnweiler, Paris, No. 2116, Photo No. 399). [1] By 1929 (Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris) [2]; By 1939, T. Catesby (Thomas Catesby) Jones [Petersburg, Va., 1880–New York, 1946]; [3] Bequest to Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA), Richmond; accessioned into VMFA collection June 11, 1947.

[1] Kahnweiler label (No. 2116) and stamp (Photo No. 399) on back of painting. The holdings of the Kahnweiler Gallery were sequestered by the French government in December of 1941 and sold at four sales in Paris: 13-14 June 1921, 17-18 November 1921, 4 July 1922 and 7-8 May 1923. No object that seems to match this painting appears in any of the sales catalogues. It is possible this work was sold prior to those sales.

[2] The work was included in an inaugural exhibition at the new Galerie Jeanne Bucher in 1929. See Affron, Matthew, John B. Ravenal, and Emily H Smith. Matisse, Picasso, and Modern Art in Paris : The T. Catesby Jones Collections at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the University of Virginia Art Museum. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2008, page 6. Fig. 7.

[3] Jones eventually purchased the work from Bucher (see Affron, p. 6). Affron also cites an inventory from the 1930s found in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Archives, including this painting, believed to be as early as 1937 and signed on one copy as 1939 (Affron, pp. 1, 14. )

[4] Accessioned June 11, 1947. Information in VMFA Curatorial and Registration files.

– Picasso: Drypoint in Max Jacob’s ‘Le Siège de Jerusalem’, D.H. Kahnweiler, Paris, 1914

— — —

A. “Medium: Oil and sand on canvas” [VMFA]

“papery and powdery procedures”

“procédures papyracées et poudreuses”

“I am using your latest papery and powdery procedures. I am in the process of imagining a guitar and I am using a bit of dust against our horrible canvas.”

– Picasso to Braque, 9 October 1912

“One can paint with anything, with pipes, stamps, postcards or playing cards, candelabra, pieces of oilskin, false collars, wallpaper, newspapers.”

– Apollinaire, 14 March 1913

“And how will art keep aristocracy alive? By keeping itself alive, as the remaining vessel of the aristocratic account of experience and its modes; by preserving its own means, its media; by proclaiming those means and means as its values, as meanings in themselves. [147] / Modernism would have its medium be absence of some sort—absence of finish or coherence, indeterminacy, a ground which is called on to swallow up distinctions. [153] / …meaning can henceforth only be found in practice. But the practice in question is extraordinary and desperate: it presents itself as a work of interminable and absolute decomposition, a work which is always pushing “medium” to its limits—to its ending—to the point where it breaks or evaporates or turns back into mere unworked material. [153/4] / And the end of its art will be likewise unprecedented. It will involve, and has involved, the kinds of inward turning that Greenberg has described so compellingly. But it will also involve—and has involved, as part of the practice of modernism—a search for another place in the social order. Art wants to address someone, it wants something precise and extended to do; it wants resistance, it needs criteria; it will take risks in order to find them, including the risk of its own dissolution. [155]“

– T. J. Clark: ‘Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art’, Critical Inquiry 9, September 1982

“Their exaggerated repugnance for beauty and for rich materials that can lead to beauty has an explanation in this fact that has been asserted to me by their friends: It seems that they are convinced and fervent Christians. Therefore they employ the humblest materials to exalt a kind of intimate, modest beauty.” [“Percio impiegano le piu umili materie, per esaltare un genere di bellezza intima, modesta.”]

– Gino Severini: Letter to Umberto Boccioni, ca. 1911, Getty Research Institute, Boccioni Archives, acc. no. 880380, Box 3, Folder 14

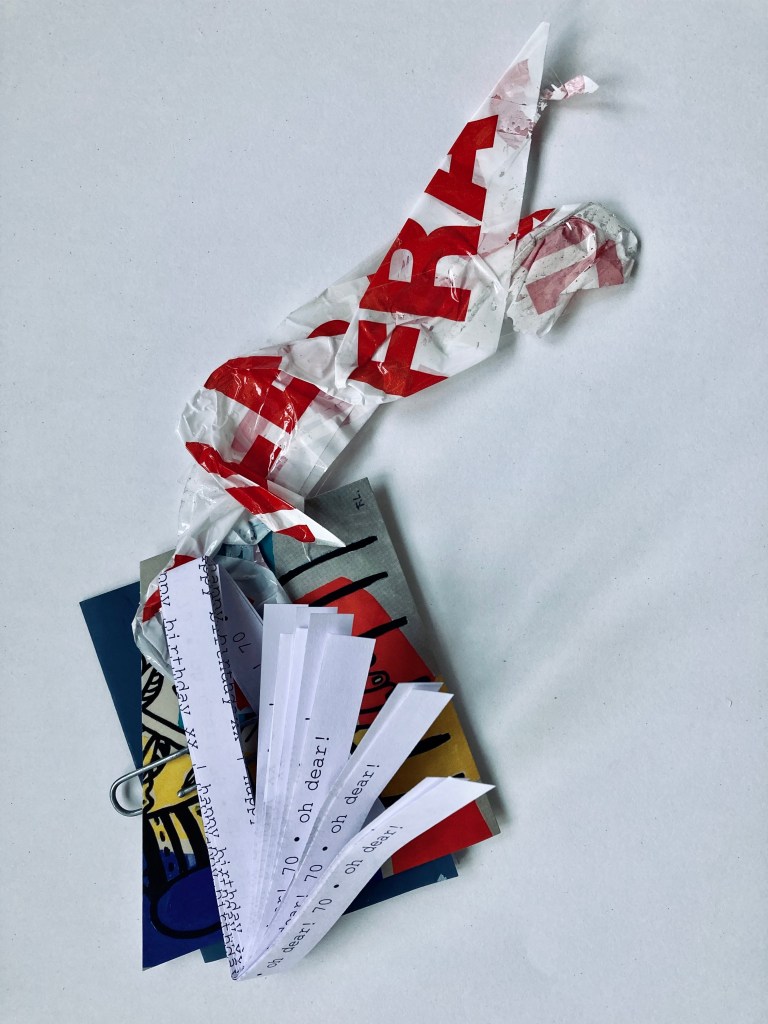

‘Collage & Text’, 25.03.2025: “the shrieking condemnation, by the tearing gesture itself, of any authorial posturing | artistic agency/what does it mean to be an artistic subject, an author”

the bricoleur is adept at performing a large number of tasks with whatever materials and tools lie at hand. / the contingent result of previous projects and occasions to renew the stock, including elements that were collected precisely because they might come in handy. / actual or potential uses / engaging the remnants of a culture in a kind of dialogue / the bricoleur “address[es] himself to a collection of oddments left over from human endeavors” / bits and pieces of cultural debris / new arrangements / units of a known but partly ruined or inoperative language. / mutable, open to substitution and transformation. / the means employed by the bricoleur will seem indirect or “devious,” despite the fact that he still works with his hands.

. . .

material fragility, formal mutability, and historical contingency / the ordinariness / creating variable visual assemblages

. . .

20.08.2024

London pavement (as found and taken), 28.01.2025

17.06.2025

ordinary techniques produced a fragile, improvised object / the selection and inventive manipulation of unlikely, preformed elements / physical (nontranscendent) acts such as cutting and folding paper substitute for traditional drawing / subvert / exchange of the codes of painting and sculpture / a mingling of optical and haptic modes / in the gap between de-skilled labor (which might be carried out by anyone) and highly skilled, “immaterial” labor that preserves a sense of artistic spontaneity in its messy, inefficient facture.

24.11.2025

. . .

—What’s that? Do you put that on a pedestal? Do you hang that on a wall? What is it, painting or sculpture?

Picasso, dressed in the blue of Parisian artisans, responded in his most beautiful Andalusian voice:

—It’s nothing, it’s el guitare!

– Christine Poggi: ‘Picasso’s First Constructed Sculpture: A Tale of Two Guitars’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 94, No. 2 (June 2012), pp. 274-298

[…as André Salmon underlines, quoting Picasso: “We are delivered from painting and sculpture, already freed from the imbecilic tyranny of genres. This is no longer this and is no longer that. It is the guitar.” – André Salmon: ‘La Jeune Sculpture francaise’, Paris, A. Messein, 1919, p103]

B. “Dimensions: Unframed” [VMFA]

And then even if in fact the ‘legendary’ question that André Lhote tells us [Maurice] Princet posed to Picasso and Braque was never formulated so precisely, it suggests that he recognized the obvious implications of what the Cubists were doing. “If that table is covered with objects equally distorted by perspective, the same straightening up process would have to take place with each of them. Thus the oval of a glass would become a perfect circle. But this is not all: this glass and this table seen from another angle are nothing more than, the table a horizontal bar a few centimetres thick, the glass a profile whose base and rim are horizontal. Hence the need for another displacement…” [ref. Henri Poincaré / n-dimensional polyhedron / the Euler–Poincaré theorem / Linda Dalrymple Henderson: ‘The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art’, Revised Edition, 2018]

– ‘La Naissance du Cubism’ in R. Huyghe’s Histoire de l’Art Contemporaine, Paris 1935, p. 80 [in John Golding: ‘Cubism: a History and an Analysis, 1907-1914’, Faber and Faber Ltd, London, 1968 (1959), p. 102]

C. “a frame within a frame” [VMFA]

The ambiguous oval shape of the canvas/table, however, immediately undermines the possibility of a univocal, literal reading since the oval may represent a round table seen from an oblique angle, seen, in fact, somewhat as a person seated at a cafe table would see it. Moreover, Picasso has emphasized the divergence of his oval canvas as object from what it represents by painting in the edges of a rectangular table, thickly across the horizontal lower edge and more thinly in a diagonal that implies recession at the right. Insofar as the edge of the table is construed as a frame, these alternate borders of the depicted table may be read as a further instance of Picasso’s use of “inner frames.” The edges of the table, in part synonymous with the enclosing border of canvas, reappear within that border, thus dismantling the traditional binary oppositions of inside/outside, work of art/exterior world.

– Christine Poggi: ‘Frames of Reference: “Table” and “Tableau” in Picasso’s Collages and Constructions’, Art Journal, Vol. 47, No. 4, Revising Cubism (Winter, 1988), pp. 311-322

“…and found the form in which parataxis possesses poetic power. / …with its abrupt advances and regressions and its abundance of energetic new beginnings, which is a new elevated style. If the life which this stylistic procedure can seize upon is narrowly restricted and without diversity, it is nevertheless a full life, a life of human emotion, a powerful life, a great relief after the pale, intangible style of the late antique legend. The vernacular poets also knew how to exploit direct discourse in terms of tone and gesture.”

– Erich Auerbach, ‘Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature’, 1946

“Je passe de la métaphore à la réalité. Je rends cette réalité tangible en usant de la métaphore.”

[“I move from metaphor to reality. I make this reality tangible by using metaphor.”]

MATERIALISE THE METAPHOR

In line with this artistic approach are ‘relief paintings’, or ‘sculpto-paintings’ according to Kahnweiler’s expression, bas-reliefs whose salient parts Picasso painted to make the light play on them. The ‘relief paintings’, of which the Picasso Museum in Paris has the most complete collection, form an intermediate artistic category, between painting and sculpture. In effect, “they are not strictly speaking paintings — whose definition is first, from a strictly formal point of view, that they have only two dimensions — because these works approach the third dimension and space through the elements in relief that compose them; but at the same time, they keep as a background, as a place where the relief is situated, a flat surface, defined by its two dimensions, which preserves for them, at first glance, the appearance of a painting.” From the compositions of the Cubist era to the relief paintings, the transition is easy, as Picasso explained to Julio González in 1931: “These paintings, it would suffice to cut them out — the colours being after all only indications of different perspectives, planes inclined to one side or the other, then to assemble them according to the indications given by the colour, to find oneself in the presence of a sculpture. Painting would not be lacking there.” Belonging neither to painting nor to sculpture, Guitar and Bottle of Bass (1913) unfolds halfway between the plane and space. Picasso turns away from modelled sculpture, in an unprecedented artistic research where the plastic poetry of the materials becomes the essential element of the composition. Blurring the boundaries of genres, the sculptor broadens the field of possibilities by introducing “non-artistic” materials into his paintings: on a tondo of wood painted in oil, a playing card in painted openwork metal thus structures the architectural organisation of the composition Glass, pipe, ace of clubs and dice (1914). The elements in relief emerge from the plane of the painting to better invest the space of the work. The conquest of the third dimension by the faceted elements detaching themselves from the plane is fully achieved in the autumn of 1913 by Mandolin and clarinet (see p. 124), where the fir panel on which the instruments appear is a component of the object itself since it gives body to the mandolin.

– Collectif: ‘La collection du Musée national Picasso, Paris’, Editions Flammarion, French Edition, 2014, pp249-250

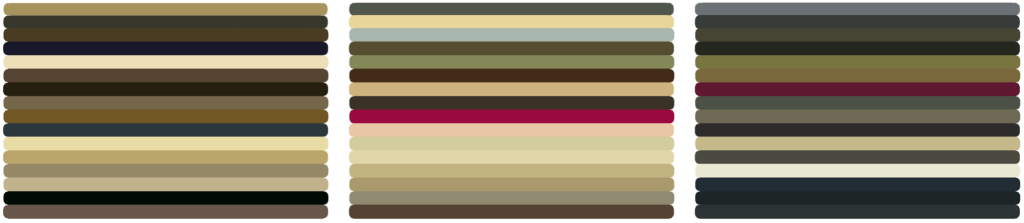

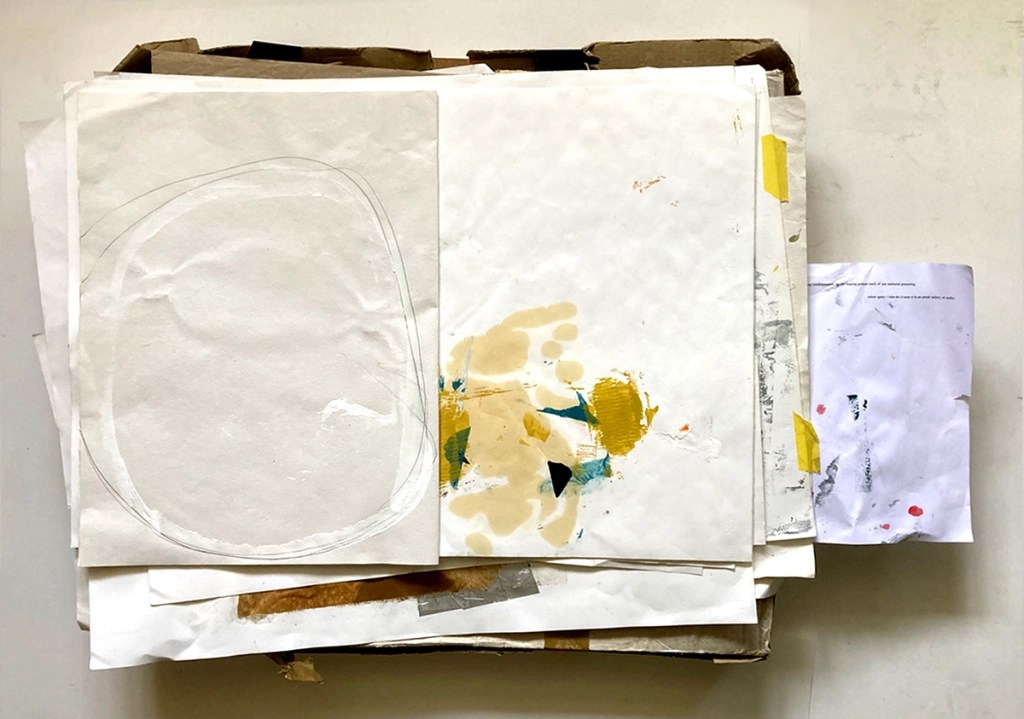

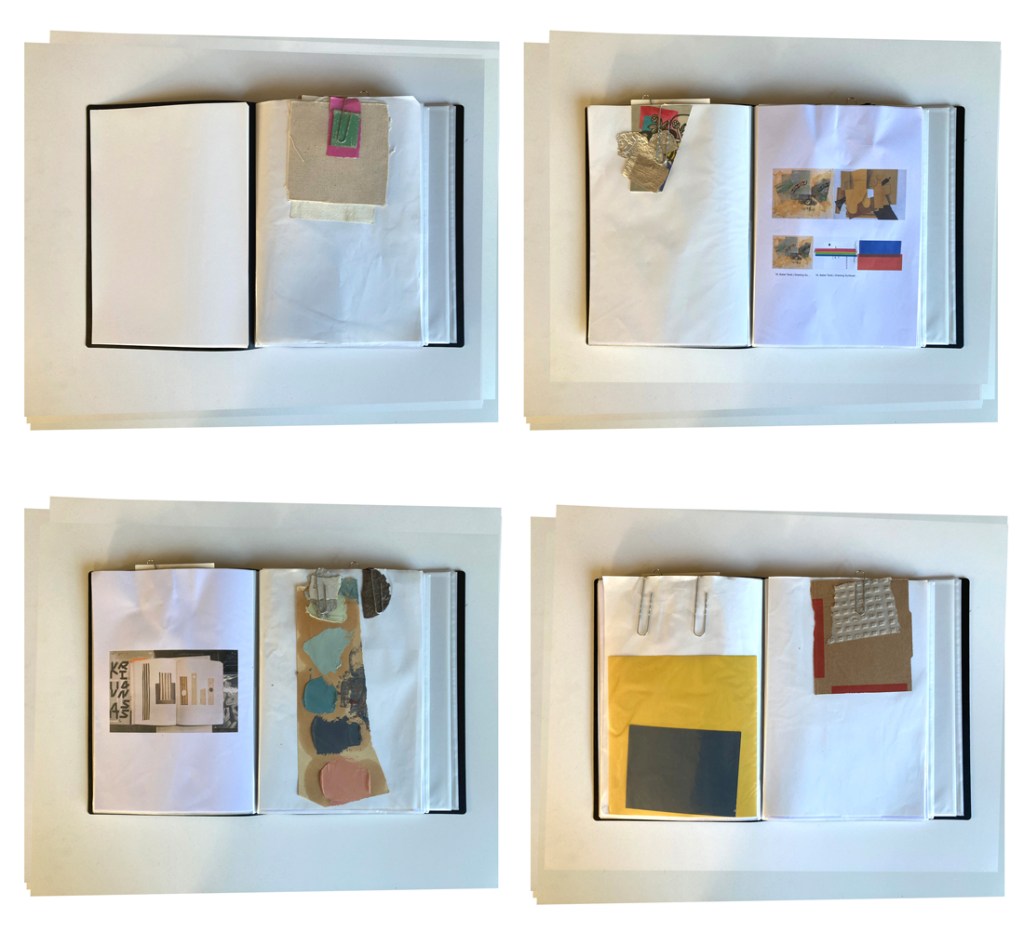

Sketchbooks 2024

Screenprinted Paper 1990

— — —

Avignon: “art of thought or thought as art”

– Susan Sontag: ‘As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Diaries 1964-1980’, Penguin, 2013

[image removed 27.02.2025] 13.01.2025: acrylic, conté crayon dust and teabag stain on tape and plan

In the summer of 1912 while Braque and Picasso were on vacation together in near Avignon, Braque noticed in a shop window some wallpaper printed to look like oak wood grain. The French call it “faux bois” meaning fake wood. Braque, with his background in illusionistic surfaces was quick to imagine the creative possibilities with this mass produced item. But he decided to surprise Picasso with his discovery so he waited until Picasso left from Avignon for a brief trip back to Paris, and while Picasso was away, Braque made “Fruit Dish and Glass” (Fig.34) (Greenberg pp.76-77).

– Anthony Plaut: ‘The Grand Trompe L’oeil of Georges Braque’, 2021

He recalled, ‘On 2nd August 1914 I took Braque and Derain to the station at Avignon. I never saw them again’ [Je ne les ai jamais revus] (Picasso, quoted in A. Danchev, Georges Braque, A Life, London, 2005, p. 121).

– Christine Poggi: ‘Picasso’s First Constructed Sculpture: A Tale of Two Guitars’, The Art Bulletin, 2012

— — —

“Let an average group of words, under the comprehension of the gaze, line up in definitive traits, surrounded by silence.”

– Stéphane Mallarmé: ‘Crise de vers’, 1897

– W. R. Lethaby: ‘Philip Webb and His Work’ / chapter ‘Some Architects of the Nineteenth Century and Two Ways of Building’, Raven Oak Press, 1979, p69

[images removed 27.02.2025] ‘papery and powdery procedures’, Royal College of Art, graphite, dry pigment and acrylic on paper laminate, 90″ x 76″, 1977, and London pavement (as found and taken), 28.01.2025

[25.02.2025]

Picasso: ‘Fruit Dish, Bottle and Violin’, 1914, National Gallery London / Aquisitions: ‘Fruit, Dish, Bottle and Guitar’ by Picasso [Marlborough Fine Art] [“and ‘Portrait of Greta Moll’ by Matisse (3 releases)] Apr 1979” / NG23/1979] / Accession number NG6449 / 92 x 73cm / Provenance: Count Etienne de Beaumont, Paris.

“…once we recognize the threat of the generic nullification of all differences, we may become extremely sensitive to the possibility that even a nondescript fragment may alert us to the birth of a singularity and increase our sense of the vanishing origins. / …such a fragment may generate a movable reciprocity between existence and nonexistence, nature and culture. / …a gap or hole whose recognition each time upsets anew the status quo in the domain of signs as well as in reality at large.”

– Gabriele Guercio & Christopher S. Wood: ‘What did the Savage Detectives Find?’, The Yearbook of Comparative Literature, University of Toronto Press, Volume 59, 2013

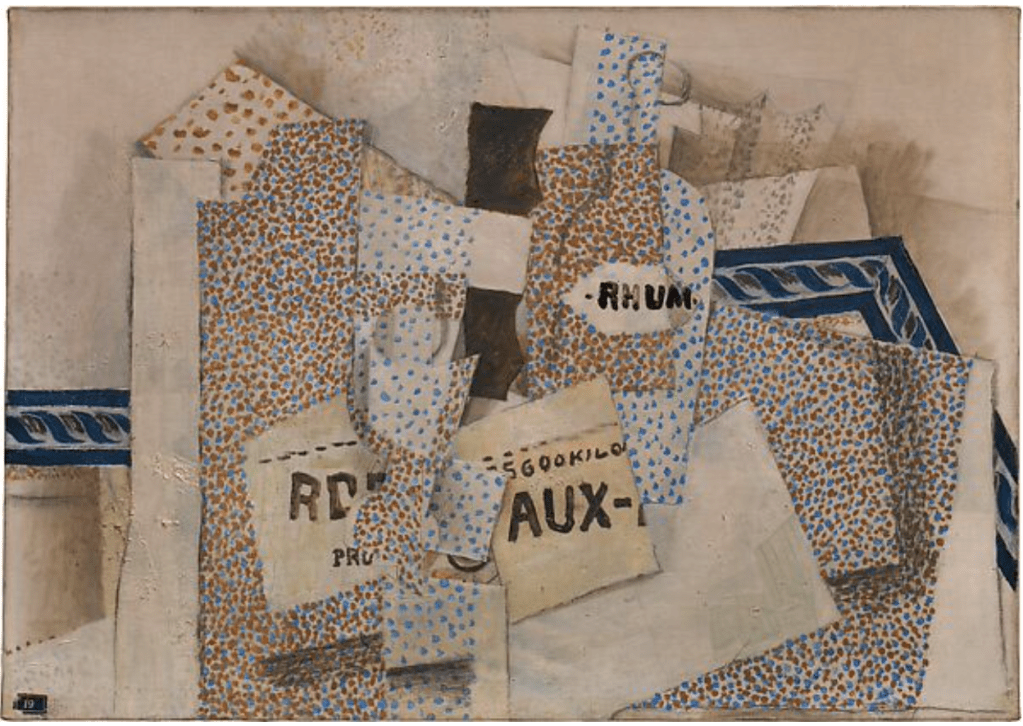

Georges Braque: ‘Bottle of Rum’, spring 1914, 46 × 54.9 cm, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, The Met Fifth Avenue, New York, Object No. SL.17.2014.1.17 [2022]

“By varying the density, size, and color of the dots on the final painted forms, Braque was able to create the impression of layered pieces of paper. The only real piece of paper on this canvas is a small lot number, “19,” at lower left. This painting was one of the almost three thousand works owned by the German-born dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, which were seized and then sold by the French government in a series of four auctions following World War I.

[. . .]

“Transmitted light…exposed numerous pinholes throughout the painting. Braque used cut-out paper shapes to plan the composition of Bottle of Rum, pinning them directly to the canvas. In certain areas, repeated pinholes indicate that Braque adjusted the shapes’ placement. Some, but not all, of the holes appear at logical anchor points that correspond to the final placement of the painted forms. A number of holes are filled with paint, while others are open, indicating that Braque pinned papers on top of the final paint layer and thus may have contemplated further changes to the composition.”

1975 & 1986

— — —

SUMMARY Rebecca Rabinow: ‘Confetti Cubism’, in Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection (MMA, 2014), pp. 162–163, 314

[1913-14] Picasso / bas-relief / unseen light source at the upper left / heavily folded, almost pleated / punctuated with staccato horizontal dashes / white paint / thickly applied with a palette knife / smoother white paint / [s]and mixed into the paint and plaster / catches the light / gritty texture / areas of stippling / narrative details…rendered in colorful dots / red dots (recalling that contemporary description of “showers of confetti fall[ing] around the ears and face”) / purple dots / quickly painted / dragged in places / not paying close attention / [Pierre Daix] ”Picasso’s first use of Pointillist stippling for decorative effect” / painted dots provide texture and luminosity and animate the surface / lightheartedness

paper confetti / 1892 Carnival celebration / Paris / “confetti” / derogatory description / Pointillists and Divisionists / [Albert Aurier] Paul Signac’s serene 1891 ‘Evening Calm, Concarneau’ [+ Albert Dubois-Pillet, Lucien Pissarro, and Maximilien Luce] = “blinding showers of multicolor confetti” / “confetti on the sidewalk” and “avalanches of confetti.”

[Troly-Curtin ‘Mi-Carême’ 1912 / “I am not speaking of ‘Confetti’ of Cubist fame… advanced painting is too subtle for me” / Gino Severini in ‘Italian Futurist Painters’ [Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in February] + Robert Delaunay at the Salon des Indépendants in March = Signac, Georges Seurat, and Henri-Edmond Cross = Apollinaire’s 1913 Pointillism = “responsible for liberating the artistic consciousness of the younger generation” / Delacroix’s “gray is the enemy of all painting” / Apollinaire’s review / Signac’s ‘D’Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionnisme’ / “very beautiful and very luminous works… of Seurat, Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Luce, Van Rysselberghe” / summer of 1912 / French government purchased Signac’s ‘Evening, Avignon (Château des Papes)’ (1909; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) = first Pointillist canvas to enter the national collections.

Austere gray-and-brown palette = Analytic Cubism / Braque and Picasso / glossy Ripolin house paint / 1913 and 1914 / fields and planes of stippling / [Ozenfant 1928] / Picasso / “scattering of points and small dots…and pretty pleasant colors” / “the taste of the embroiderer or lace-maker” / [Alfred H. Barr] / “rococo cubism” / Braque and Picasso = optical mixing of colors / Braque 1914 ‘Bottle of Rum’ = different approach [from Picasso] varying both the colors and the densities of his overlapping stippled passages.

‘Bottle of Rum’ / still life arranged on a table in the corner of a room / sans-serif font of the letters on the now—faded, yellowish areas representing a printed page—“RD[E?],” “AUX-[P? 8?],” “5600 KILO[M?], “PR[O?]” / “BO[RD]e[AUX-P]aris” race, an overnight cycling competition / 560 kilometers / Braque = an avid cyclist / promotional materials for Motobloc, an automobile manuacturer with factories in Paris and BORDEAUX-Blastide.

late 1913 or early 1914 / Braque / Motobloc advertisement in ‘Bottle, Glass, and Newspaper’ / layered pieces of newspaper and faux bois wallpaper / passages of colorful dots / varying densities, sizes, and hues of the dots [. . .] in light blue, reddish burnt sienna, a now-faded yellowish raw sienna, gray, and burnt umber / overlapping planes / distinguishable contours / appear absolutely flat, as if each were cut from a sheet of decorative paper / dozens of pinholes in the canvas are an indication that Braque used paper templates as he worked.

Spring 1914 / Braque = Bottle of Rum / Picasso = speckled mauve wallpaper into his collages / [both] flat areas of dots = two-dimensional sculpting medium / ‘Bottle of Rum’ / Braque / black Conté crayon = the illusion of volumetric forms emerging from the flat stippled passages, suggesting the left side of the rum bottle, the circular top of the glass, and the corner of a rectangular form at right = trompe-l’oeil bas-relief / top and left perimeters of the canvas = stippling with a thin wash of white paint / “not to conceal it but rather to create translucency and the related corollaries of depth, texture, and light.”

Braque / “confetti” criticism / Signac exhibition / Galerie Bernheim-Jeune / November-December 1913 + Seurat paintings owned by his friend and boxing partner Richard Goetz / ‘Bottle of Rum’ = pseudo-pointillist passages = luminous planes from which he constructed volumetric forms.

[1913 and 1914] ‘Cubist confetti’ = height of chic / fashion designer Paul Poiret / chiffon fabrics + scatterings of colorful ‘confetti cubes’ / designs / sprinkling square-cut confetti onto paper and painting prototypes based on how they landed / “from head to foot as if it snowed red, yellow, green, blue bits of paper” = Cubists’ visual vocabulary / confetti showers as a phenomenon of optical mixing within three-dimensional space + jubilant and rowdy popular culture.

Revision | 08.12.2025

[, ponderous loco mobile omnibuses lose themselves and pump ponderously into uninteresting little side streets, and] / [On Shrove Tuesday preceding Lent Paris takes a breath before fasting and goes mad for the day and night.] / [. None of the harsh stinging stuff, no plaster-of-Paris, or red pepper as at Milan and Coney Island—that is not the Parisians’ idea of wit or pleasure! The showers are soft and…]

“…and the dust of the streets rises to meet the dust of the confetti, whilst through this haze the electric light shines with bizarre delicacy.” / ‘All the Things You Are’ / “You are the dust of the streets that rises / To meet the dust of the confetti.” / “And the feet of the dancers riseTo meet the feet of the dancers.”

80,000 bags (20,000 kilograms) of soft paper confetti / 500,000 kilograms / the country’s flagging paper industry / “Confetti Rain” / conficere (“to prepare, to make ready”) / waste from punched-paper factories / “I dislike confetti…” / “Time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time.”

finding little paper dots in one’s drink / to incorporate a “found” object / the sixth is covered in sand / the areas of colorful dots, which were painted on white to provide more contrast / passages of stippling, or fields of small colored flecks / staccato horizontal dashes that signify printed words / purple dots / quickly painted—the brush dragged in places / white lines were formed by the negative space

“blinding showers of multicolor confetti” / “confetti on the sidewalk” and “avalanches of confetti”

glossy Ripolin house paint / “scattering of points and small dots…and pretty pleasant colors,” as “the taste of the embroiderer or lace-maker” / dots are monochromatic

“RD[E?],” “AUX-[P? B?], 5600 KILO[M?], “PR[O?]” / “BO[RD]e[AUX-P]aris”

dozens of pinholes in the canvas / the flat areas of dots / a two-dimensional sculpting medium / a thin wash of white paint / translucency / the related corollaries of depth, texture, and light / luminous planes / sprinkling square-cut confetti onto paper and painting prototypes based on how they landed / optical mixing within three-dimensional space / jubilant and rowdy popular culture

[confetti, dust, translucency, optical vibration, foundness, and Cubist procedure]

1. Where dust meets confetti, vision begins.

2. Meaning rises like dancers’ feet meeting their own echo.

3. Confetti is the city briefly celebrating its own debris.

4. Soft paper storms reveal the structure of joy.

5. Translucent planes are the new carnival lights.

6. Every painted dot remembers the industry that cut it.

7. A pinhole is a decision the painting hasn’t forgotten.

8. Confetti rain turns the street into a grammar of colour.

9 Optical mixing is the choreography of dust.

10. Stippling is a quiet riot.

11. Negative space is the sharpest line you can draw.

12. Flat dots become sculptural when they refuse depth.

13. Found things teach the canvas how to think.

14. A thin white wash is enough to make light reconsider itself.

15. Avalanches of colour teach the eye to waste time beautifully.

16. Printed fragments speak in staccato.

17. Confetti is popular culture falling upward.

18. The canvas is a carnival of pinholes and propositions.

19. To scatter is to compose.

20. What shimmers in the haze is not the lamp, but the structure of delight.

— — —

1. Dust learns itself through falling.

2. Colour becomes thought when it disperses.

3. A point is a pause disguised as matter.

4. Light fractures to remember its origin.

5. Surfaces speak by refusing depth.

6. The world is most legible when it dissolves.

7. Translucency is structure in a state of becoming.

8. Chance performs its own geometry.

9. Space thickens when touched by repetition.

10. Fragments decide what the whole will be.

11. A hole is the memory of an intention.

12. The plane brightens where meaning thins.

13. Vision vibrates when matter hesitates.

14. To scatter is to articulate.

15. Silence appears where colour gathers.

16. Form begins again at every fleck.

17. Perception rises to meet what falls.

18. Order is simply the rhythm of interruptions.

19. Light speaks most clearly through residue.

20. Nothing is more structural than drift.

World Cup, Argentina, 1978 / Exeter School of Art & FB 25.05.2024

Summary of Winthrop Judkins’s ‘Fluctuant Representation in Synthetic Cubism: Picasso, Braque, Gris, 1910–1920’ (Harvard dissertation 1954, Garland Publishing 1976):

Key Themes in Winthrop Judkins’s Fluctuant Representation in Synthetic Cubism

1. Synthetic Cubism as a Transformative Mode of Seeing

Judkins analyses how artists like Picasso, Braque, and Gris in the Synthetic Cubism period moved away from conventional perspectives, instead crafting works composed of flat planes, overlapping materials, and mixed media. This creative shift redefined representation, emphasising assembly and emergence over illusion and depth.

2. Deconstructing Representational Certainty

Through techniques like collage and papier collé, Cubist artists broke down object-hood into fragmented signs and diverse materials—evoking the chaos of modern life. The use of newspaper, wallpapers, and everyday fragments destabilised the viewer’s reliance on a single coherent viewpoint or optical realism.

3. Fluctuant Representation: Open to Multiple Readings

The core concept of “fluctuant representation” lies in its intentional ambiguity and fluidity—forms that oscillate, identities that overlap, surfaces that both reveal and conceal. Judkins sees this as central to Synthetic Cubism’s vision: a deliberate multiplicity of readings that defy fixed interpretation.

4. Aesthetics of Instability and Iridescence

Judkins notes recurring formal qualities which foreground instability—not as failure, but as aesthetic and conceptual strength:

- Deliberate oscillation of appearances

- Studied multiplicity of readings

- Conscious compounding of identities

- Iridescence of form.

5. Synthetic Cubism as Provocation of Perception

Judkins suggests that Cubism didn’t merely represent the world—it questioned how we perceive it, revealing how our sensory expectations can be unsettled and remade.

Summary Overview

Judkins’s Fluctuant Representation in Synthetic Cubism charts how early Cubist artists reconfigured visual language through fragmentation, layered materiality, and perceptual ambiguity. This led to artworks that demand active, interpretive viewing—eschewing stable representation for dynamic, multi-faceted engagement.