Essay 10.02.2026

Beneficial practice

Abstract

Beneficial practice stresses making as an ethical, socially engaged activity. Drawing on W.R. Lethaby’s writings, it treats art, architecture, and labour not as spectacle or self-expression, but as attentive work oriented toward collective use and real-world needs. Skill, care, and responsiveness to materials, places, and people all become essential, while preordained design, and market-driven metrics are resisted and hopefully abandoned. Referencing Antonio Negri, knowledge emerges through doing, and is situated in collaborative, consequential practice. In emphasising slowness, presence, and sustained social relations, beneficial practice offers a model of making that contributes to the common good: the collective “well-doing of what needs doing.”

Making, ethics, labour and the common good

The language of practice has become strangely anaemic. In art schools, design studios and policy documents alike, it is invoked as a neutral descriptor: a set of techniques, a professional identity, a career path. What drops out of view is the older, more demanding sense of practice as an ethical relation to the world — a way of doing things well, because they are done with and for others.

The idea of beneficial practice, articulated with particular clarity by the architect, architectural historian and arts educator W. R. Lethaby, offers a sharp corrective to this thinning-out. It insists that making is not merely productive, expressive or innovative, but potentially socially grounded, materially attentive and oriented toward collective use rather than private display.

This a challenge to a culture that increasingly separates thinking from doing, design from labour, and expertise from lived experience.

Doing what needs doing

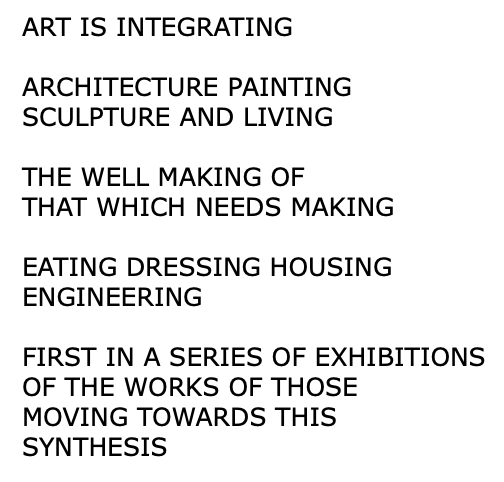

ART IS INTEGRATING

ARCHITECTURE PAINTING / SCULPTURE AND LIVING

THE WELL MAKING OF / THAT WHICH NEEDS MAKING

EATING DRESSING HOUSING / ENGINEERING

THE FIRST IN A SERIES OF EXHIBITIONS / OF WORKS OF THOSE / MOVING TOWARDS THIS / SYNTHESIS

– ‘Coventry of Tomorrow, Towards a Beautiful City’, May 1940

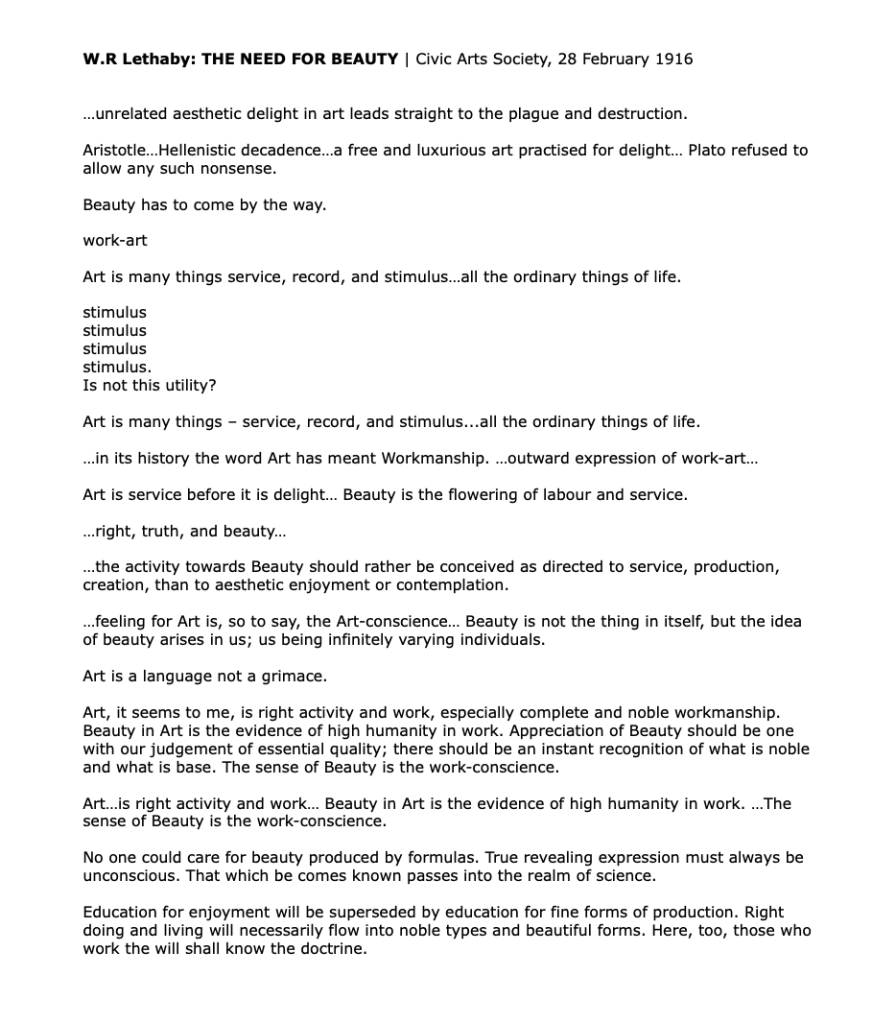

Lethaby’s phrase in The Imprint (1913), often paraphrased as “the well-doing of what needs doing”, is deceptively simple. Writing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Lethaby rejected the idea of art as a rarefied activity reserved for galleries or elites. For him, art was not a category of objects but a quality of action — something that emerges when the ‘doing’ is done attentively, skilfully and in relation to real needs.

Philip Webb’s architecture — modest, vernacular, resistant to grandiosity — exemplified this ethic in built form. As Lethaby observed in essays later collected in ‘Form in Civilisation’ (1922), Webb’s buildings do not announce themselves as ‘Art’. They grow out of use, site and material constraint. They are shaped less by stylistic ambition than by a refusal to do more than is necessary — and a refusal to do that carelessly.

What matters here is not style but orientation. Beneficial practice begins from use, not representation; as service, not spectacle.

Against abstract mastery

Running through Lethaby’s writing is a suspicion of abstract systems imposed from above. He was deeply sceptical of design methods that treated making as the execution of pre-existing ideas, rather than as a process of discovery through material engagement. Drawing, in his account, is not the sovereign origin of form but one moment in a longer conversation between hand, eye, material and circumstance.

This matters because abstraction, when detached from making, easily turns authoritarian. The planner’s diagram, the architect’s masterplan, the artist’s concept statement — all risk substituting representation for reality. For Lethaby, knowledge must remain answerable to the situation in which it operates.

In this, Lethaby converges with much later critical theory. Antonio Negri, writing from within Italian Operaismo [‘workerism’] and post-Marxist philosophy, describes knowledge not as a static possession but as a dynamic expression of living labour — the collective, creative intelligence that produces social life itself. In ‘Art and Multitude’ (2009), Negri argues that artistic practice becomes politically significant precisely when it refuses autonomy and re-enters the round of common production.

For both Lethaby and Negri, truth does not precede practice. It emerges from it.

Practice as a social relation

What distinguishes beneficial practice from craft romanticism is its insistence on the social dimension of making. Lethaby’s admiration for medieval building cultures — guild-based, collaborative, slow — was not a call to return to the past, but a way of highlighting what modern production had lost: the sense that work is a shared activity where value is measured in use and durability rather than speed or novelty.

This resonates with contemporary debates on social practice, participatory art and place-based work. Too often, these practices are evaluated in terms of visibility or symbolic impact, rather than their capacity to sustain relations over time. Beneficial practice offers a different way of thinking: does the work remain open to others? Does it respond to real conditions? Does it leave something usable behind?

Planning provides a clear example. The planner necessarily operates through abstraction — maps, policies, projections. Communities, by contrast, live within evolving, unfinished realities. When planning becomes insulated from lived feedback, it fails. When it remains porous — revised through encounter, negotiation and repair — it becomes a form of collective intelligence rather than managerial control.

Beneficial practice does not abolish expertise; it situates it. As Lethaby writes (The Builder, 1925): “The main difficulty was how to deal with obviously weak and fractured walls without pulling down and rebuilding. This Webb accomplished by mining into a patch of the wall on the inside and filling with strong new work, then by forming another hole next to the filled part the work could be extended by degrees in a band throughout a wall.”

Skill, care and attention

There is an ethical demand embedded in all this. Beneficial practice requires skill — not as credential, but as attentiveness. To work well is to notice resistance, limitation and contingency. It is to accept that materials have their own tendencies, that places have their own rhythms, and that outcomes cannot be fully known in advance.

Simone Weil, writing from a very different tradition, described attention as the rarest and purest form of generosity. As such, the value of making lies not in self-expression but in sustained care: care for materials, for users, for the shared world that work helps to shape.

This is why beneficial practice cannot be reduced to method, or be used as a toolkit or a checklist. It is a position: an openness towards being changed by what one does.

Why this still matters

In a culture saturated with images, simulations and accelerated production cycles, beneficial practice insists on slowness, presence and consequence. It challenges the idea that innovation must always mean novelty, or that value must be immediately legible and/or marketable. Instead, it re-centres making as a form of social labour whose effects unfold over time.

To speak of benefit today is unfashionable. It sounds moralistic, even naïve. But Lethaby’s point is sharper than that. The question is not whether work is morally pure, but whether it contributes to shared life or merely extracts from it.

Beneficial practice offers the possibility that, in doing what needs doing / making what needs making — carefully, collectively, and without excess — we might recover a sense of meaning that cannot be designed in advance, but only discovered together.

References:

W.R. Lethaby: ‘Art and Workmanship’, The Imprint, January 1913

W.R. Lethaby: ‘Form in Civilization: Collected Papers on Art & Labour’, Oxford University Press, 1922

W.R. Lethaby: ‘The Builder’, Issue 4305, Vol. 129, 7 August 1925, pp. 220–222 https://archive.org/details/sim_building-uk_1925-08-07_129_4305/page/222/mode/2up [accessed 10.02.2026]

Antonio Negri: ‘Art and Multitude: Nine Letters on Art, Followed by Metamorphoses: Art and Immaterial Labour’, Polity, 2011

Simone Weil: ‘Gravity and Grace’, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952.

© David Patten, 2026 [1,268 words]

– W.R. Lethaby: ‘Art and Workmanship’, The Imprint, January 1913

WORKING NOTES

“For him the substance of discipline was in using practical and artistic genius to enter the world and yet go beyond the world…”

– Li Tongxuan: ‘Entry into the Realm of Reality: The Guide. A Commentary on the Gandavyuha, the final book of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra (trans. Thomas Cleary), Shambhala Publications Inc, 1989

21.06.2025 | Summary of two texts:

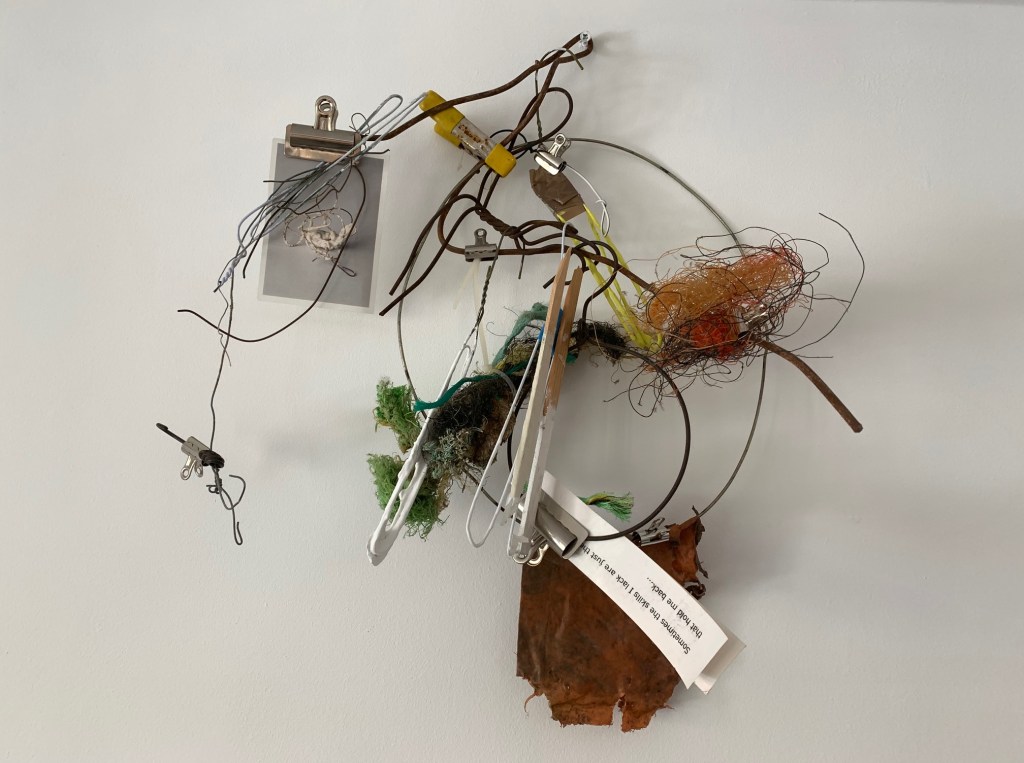

The work resists traditional structure and coherence, favouring an informal, process-driven approach where conventional order and artistic hierarchy are absent. Instead, it embraces a raw, experimental mode of creation using everyday materials and actions—cutting, folding, stacking—blurring boundaries between painting and sculpture, skilled and unskilled labour, and finished and unfinished states. It becomes a record of gesture, thought, and making—a provisional archive of spontaneous, physical experimentation rather than a resolved, singular artwork.

Abstract

[v. 25.08.2025]

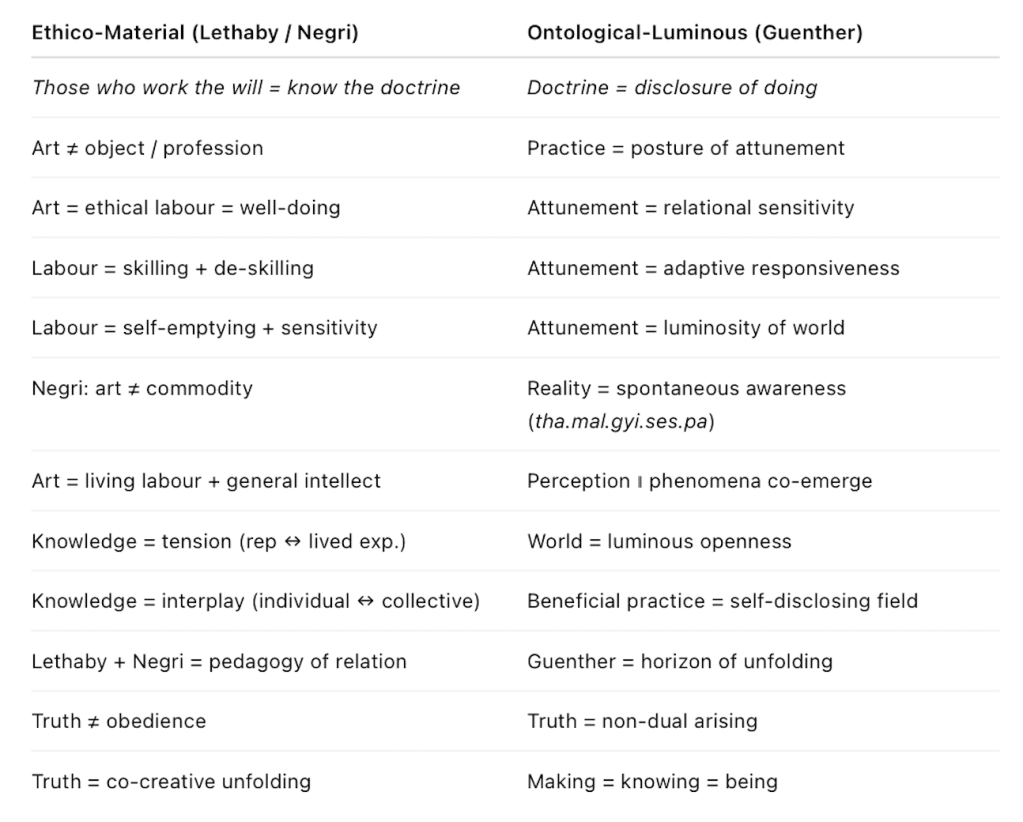

Lethaby: Those who work the will = know the doctrine.

Doctrine ≠ code.

Doctrine = lived disclosure of doing.

Art ≠ object.

Art ≠ profession.

Art = ethical labour = the well-doing of what needs doing.

Labour = skilling + de-skilling.

Labour = secular self-emptying + relational sensitivity + transformative embodiment.

Negri: art ≠ commodity.

Art = living labour + general intellect.

Knowledge = tension (representation <-> lived experience).

Knowledge = interplay (individual making <-> collective intelligence).

Lethaby + Negri = relational pedagogy of practice.

Truth ≠ obedience.

Truth = co-creative unfolding of labour.

Beneficial practice = skill + care + openness.

Situated knowledge = making + doing.

Ecclesiastes 9:10 = do with all one’s might.

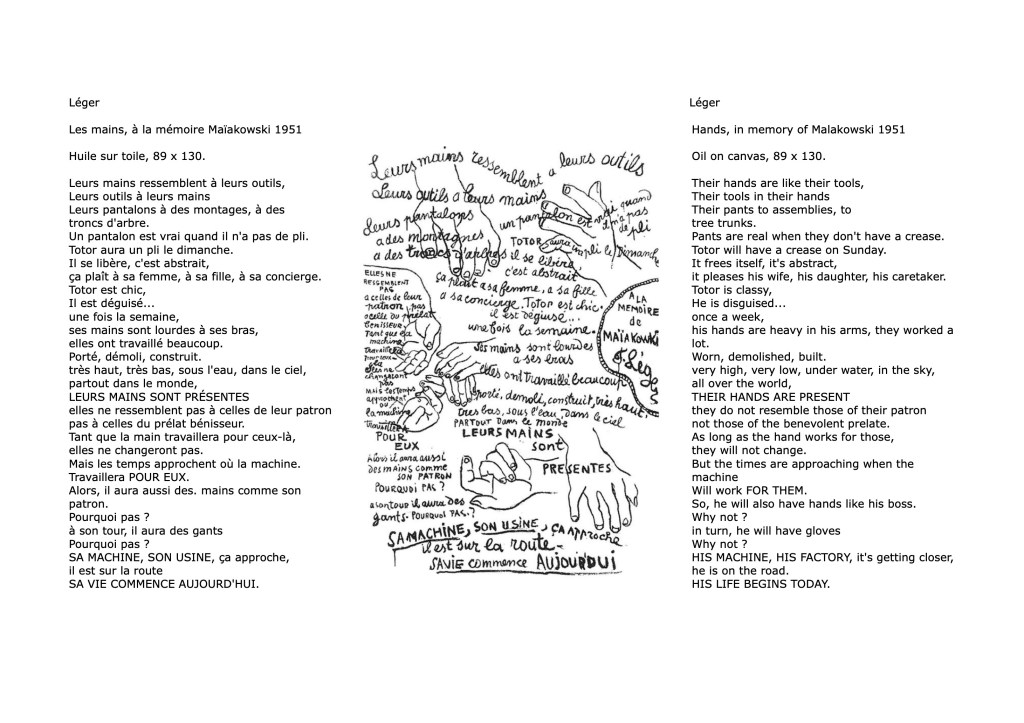

Léger = the hand monumentalized.

Marshall = tacit, atmospheric knowledge.

Practice = living field where significance + service emerge.

Guenther: reality = spontaneous, uncontrived awareness (tha.mal.gyi.ses.pa).

Perception | phenomena.

World = luminous openness.

Beneficial practice = posture of attunement.

Attunement = relational sensitivity + adaptive responsiveness + self-disclosing luminosity.

Equation of the whole:

Lethaby’s will + Negri’s labour -> Guenther’s unfolding.

Making = knowing = being = luminous.

Reading W. R. Lethaby and Antonio Negri together foregrounds an understanding of practice in which art is not a rarefied object or profession but the ethical labour of “the well-doing of what needs doing.” Lethaby’s insistence that “those who work the will shall know the doctrine” places practice before precept, locating truth not in abstract formulation but in the lived understanding that unfolds through embodied action. In his vision, art is inseparable from the ethical orientation of labour, from skilling and de-skilling, from secular self-emptying, relational sensitivity, and transformative embodied practice.

Negri extends this vision into the domains of living labour and the general intellect. For him, art is not commodity but an expression of collective, creative activity that generates and sustains the common. The tension between representation and lived experience, between individual making and collective intelligence, becomes the generative space in which knowledge arises. Lethaby and Negri together articulate a relational pedagogy of practice, in which truth is generated not through obedience to a given code but through the co-creative unfolding of labour itself.

This ethico-material grounding resonates with a broader framework of beneficial practice—an orientation toward making and doing in which skill, care, and openness to others generate situated knowledge. The injunction at Ecclesiastes 9:10 to “do with all one’s might,” Fernand Léger’s celebration of the hand, and Alfred Marshall’s atmospheric sense of tacit knowledge each echo this dynamic interplay of making and shared intelligence. Practice here is not mere instrumentality but a living field in which significance and service emerge through attentive engagement.

Herbert V. Guenther’s articulation of Dzogchen awareness offers the ontological horizon within which this pedagogy of practice can be developed. In Guenther’s reading, reality is a field of spontaneous, uncontrived awareness—tha.mal.gyi.ses.pa—where perception and phenomena co-emerge in luminous openness. Within such a ground, beneficial practice becomes more than an ethical discipline: it is a position of being attuned to relational sensitivity, adaptive responsiveness, and the self-disclosing luminosity of the world itself. Thus, what begins in Lethaby’s call to “work the will” and Negri’s celebration of living labour finds its fullest horizon in Guenther’s vision of practice as the site of non-dual unfolding—where making, knowing, and being are inseparably luminous.

Draft Texts 2020-2025 v.18.08.2025

Working Space

Lethaby: materiality of practice, ethical-aesthetic ontology of art = art as inseparable from life, from work, and from the “well-doing of what needs doing” / art is not a discrete professional activity but an integrated mode of social labour, rooted in shared culture + in right relationships to materials, environment, and people / situates art firmly within the social and labour-based dimensions / art = collective making, grounded in necessity and meaning, rather than luxury or decoration / dissolves the ‘art object’ as an isolated entity / art = a mode of being-in-relation.

Negri: political ontology of labour and subjectivity via constituent power, the common, and living labour / art = expression of living labour = creative, affective, and relational capacities that exceed and resist capitalist capture / art = instance of constituent power / not merely representational but actively produces new social realities = a praxis that participates in the continual constitution of ‘the common’ / art = collective becoming / art = part of the self-production of life itself = an insurgent activity against forms of dead labour (commodities, fixed meanings, static institutions).

“the social, labour-based, and ontological dimensions of art”

Shared rejection of art as isolated object:

[Lethaby] rejects art as mere luxury + [Negri] rejects art as commodity = art as embedded in processes of life and collective production.

Labour as creative and relational:

[Lethaby] skilled, ethical, situational making (rooted in Ṛta/Sukṛta) [#25.01.2021 Sukṛta | WELL-DOING/WELL-MAKING] + [Negri] living labour = autonomous source of value and social transformation.

Ontology as co-creation:

[Lethaby] art inseparable from the conditions and relations of its making + [Negri] art inseparable from the political = process of constituting the common.

Synthesis:

social dimension = art as the shared, relational ground in which it is produced and received.

labour-based dimension = the integration of making, doing, and living labour into the act of art.

ontological dimension = art as both an activity and a mode of being = reconfigured relations between individuals and groups.

W. R. Lethaby (1857–1931) = (essay) ‘The Builder’s Art and the Craftsman’ [published in ‘Architecture a Profession or an Art: Thirteen Short Essays on the Qualifications and Training of Architects’, edited by R. N. Shaw and T. G. Jackson (London: John Murray, 1892)] = “the arts of building” = “the easy and expressive handling of materials in masterly experimental building” = “The separation of the two necessarily makes design doctrinaire – a hot-pressed-paper-craft – and workmanship servile; degrading even in the ordinary necessities of building; destructive to ornamentation; a mere insult and pretence of art at which sculptors and painters do well to make a mock” / first Principal of the Central School of Arts and Crafts = the integration of art, architecture, craft, and everyday life / “the well-doing of what needs doing” = art as an ethical and social practice — not an elite pursuit / something inseparable from the making of housing, clothing, tools, and the built environment = [‘Coventry of Tomorrow’, May 1940] “art is integrating architecture… and living”

The Bauhaus (founded 1919 by Walter Gropius) = Arts and Crafts ideals, inc. Lethaby’s holistic integration of art, craft, and design / Bauhaus curriculum combined architecture, craft, engineering, and everyday design / Bauhaus influence spread into British architectural education during the interwar and immediate post-war period / via émigré architects and through institutional reforms.

The Liverpool School of Architecture (under Charles Reilly and later Lionel Budden) = conduit for modernist and Bauhaus-influenced ideas in Britain / (1930s) visits by Erich Mendelsohn and Walter Gropius (1934) / architecture should integrate art, engineering, and social planning -> senior planning and architecture posts in post-war reconstruction projects inc. Coventry.

Donald Gibson (attended Manchester School of Architecture) (taught Liverpool School of Architecture 1933-1935) / appointed Coventry’s first City Architect in late 1938 PLUS Percy Johnson-Marshall (1915-1993) (attended Liverpool School of Architecture) appointed Planning Architect at Coventry 1939 (to 1941) / branch secretary and organiser of local branch of Association of Architects, Surveyors and Technical Assistants.

Percy Johnson-Marshall was a great admirer of Sir Donald Gibson, Chief Architect-Planner of Coventry, as the exemplar of the socially committed public architect. In 1938, after completing his architectural and planning courses, he was appointed to Gibson’s staff. It proved a stimulating relationship for them both. Gibson was promoting a radical redevelopment plan for the centre of Coventry, introducing a traffic-free shopping centre for the first time in Britain. This proved difficult to sell to the council until in 1941 the Nazis blitzed Coventry and devastated the heart of the city. An even bolder plan became possible, and Johnson-Marshall, his own house wrecked, threw himself wholeheartedly into the challenge, knowing that his call-up to the army was imminent. Rotterdam was seriously bombed in the same year, and Johnson-Marshall gained inspiration from that city’s chief planner, Cornelius Van Traa. Rotterdam and Coventry became twin cities and their innovative plans were realised after the war. / It was typical of Johnson-Marshall that from his army camp in England, torn away from his compelling task, and shattered by the death of his young wife, he rounded up his contemporaries, most of them in uniform, and persuaded them to produce sketch designs for public buildings destined for allotted sites on the master-plan, to give realism to the presentation drawings and model. / Just before the war, Lewis Mumford’s seminal book The Culture of Cities had appeared in Britain. Ranging over the city in history and exploring the social potential of modern planning organisation, it was just the nourishment that the frustrated young architects and planners needed. It made an enormous impression on Johnson-Marshall, and Mumford became his guru. [Robert Gardner-Medwin: Obituary: Professor Percy Johnson-Marshall, Obituary, 15 July 1993, The Independent ] [Note: thesis: https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/id/eprint/53223/1/WRAP_Campbell_paper_dream_city_current.pdf]

Coventry Archives CCA/TC/27/1/6/1

‘Art and Architecture’ = as socially integrated, labour-based acts of making for everyday life’ = “Art is integrating architecture painting sculpture and living… the well making of that which needs making” = synthesis across disciplines / Gibson’s vision for Coventry = cultural and social life of the city as part of the physical reconstruction / aligning with Lethaby’s view of art as embedded in living and working PLUS Abercrombie + Patrick Geddes = (slogan) ’The Idea / To Avoid Chaos we must PLAN our city for all needs’ + models, etc., from MARS Group, Marcel Breuer, et al.

‘Coventry of Tomorrow, Towards a Beautiful City’, May 1940

Lethaby -> Arts and Crafts holistic ethos -> Bauhaus integrates these ideals into modernist pedagogy -> Liverpool School of Architecture transmits and adapts them into British architectural training -> Donald Gibson applies them in Coventry, producing a civic statement that distils the same integrated vision.

Lethaby: “the well-doing of what needs doing” = making as an integrated social and ethical activity, dissolving the boundaries between ‘architecture, craft, engineering, and the necessities of daily life’ = Arts and Crafts Movement + Bauhaus = a modernist context, uniting art, design, and industry in service of social renewal -> the post-war reconstruction / 1940 statement for Coventry of Tomorrow — “Art is integrating architecture painting sculpture and living… the well making of that which needs making” = Lethaby’s language + the Bauhaus ambition to merge aesthetic and technical disciplines with the fabric of everyday social life.

The ‘Coventry of Tomorrow, Towards a Beautiful City’, May 1940 exhibition statement: “Art is integrating architecture painting sculpture and living… the well making of that which needs making” -> Negri’s political ontology of labour and subjectivity as an expression of constituent power: the collective, self-organising capacity of people to produce new social realities / the integration of disciplines and life-activities in Gibson’s vision = aesthetic synthesis + mobilisation of living labour = the creative, relational, and cognitive capacities of workers, designers, engineers, and citizens alike / directed toward the common: shared spaces, resources, and forms of life that sustain collective flourishing / “the well making of that which needs making” = Negri’s insistence that labour, when autonomous from capitalist command, becomes ontologically generative = not only objects but new modes of being-together / the social, labour-based, and ontological dimensions of art converge: art is not a separate sphere of cultural refinement, but an active process of shaping the common world, embodying a politics of production that is at once material, aesthetic, and emancipatory.

Lethaby’s conviction that art is “the well-doing of what needs doing” framed creative work as an integrated social and ethical activity, dissolving the boundaries between architecture, craft, engineering, and the necessities of daily life. Holistic ethos = Arts and Crafts Movement + vision of the Bauhaus (Walter Gropius and his colleagues reinterpreted the English reformers’ principles for a modernist context) = uniting art, design, and industry in service of social renewal.

In Britain, these ideas were transmitted through institutions such as the Liverpool School of Architecture, where figures like Charles Reilly and Lionel Budden embraced and adapted the Bauhaus synthesis of artistic, technical, and civic concerns. Donald Gibson, a Liverpool-trained architect who became Coventry’s first City Architect in 1938, absorbed this lineage and applied it to the post-war reconstruction of the city. The 1940 statement for ‘Coventry of Tomorrow’ — “Art is integrating architecture painting sculpture and living… the well making of that which needs making” — distils this inheritance, directly echoing Lethaby’s language while embodying the Bauhaus ambition to merge aesthetic and technical disciplines with the fabric of everyday life.

Gibson’s vision also becomes an assertion of constituent power / [Negri’s political ontology of labour and subjectivity] / the collective capacity of people to produce new social realities. The integration of disciplines and life-activities is not only an aesthetic synthesis but a mobilisation of living labour — the creative, relational, and cognitive capacities of workers, designers, engineers, and citizens alike — directed toward the common. In this light, “the well making of that which needs making” resonates as an ontologically generative act, producing not just artefacts but new forms of being-together, where the social, labour-based, and ontological dimensions of art converge in the active shaping of a shared world.

Integration of Art + Labour + Life

Representation = planner’s vision / Gibson = work with conceptual synthesis: an integrated vision of architecture, engineering, and everyday life as a harmonious whole.

Vision = mediated = exhibitions, masterplans, public statements / inevitably abstracted from the immediate lived realities of communities / 1940 Coventry of Tomorrow statement = representation constructed from professional, aesthetic, and political ideals = of what the city should become.

Experience = community’s life-world = complex realities shaped by existing relationships, histories, and needs = immediate, embodied, and contingent, often valuing familiarity, local improvisation, and incremental change over wholesale transformation / not aligned with a planner’s representation or integrated model.

[Negri] constituent power resides with the people / living labour = always in motion, plural, and unpredictable vs fixed and coherent formal synthesis of Planning = risks the lived, evolving nature of the common which becomes subordinated to an already-imagined order = top-down imposition rather than a co-created expression -> resistance or reinterpretation of planned vision = alternative spatial practices that challenge the official representation.

Beneficial Practice = emphasis on adaptive capacity, relational sensitivity, and self-emptying = the tension between representation and experience = feedback loop -> share constituent design processes = design as provisional, open to revision through lived use / common = not fixed in the plan but continually produced through ongoing social and material relations.

However, such an integrated vision inevitably navigates a tension between representation and experience. The planner’s synthesis, however grounded in ethical-aesthetic and labour-based ideals, is still a projection — a representation of what the common should be. Communities, by contrast, live within the unplanned, evolving realities of everyday life, where needs, attachments, and uses may not align with the designer’s model. In Negri’s terms, constituent power resides in the lived activity of living labour, which cannot be fully fixed in advance. If this tension is approached through beneficial practice — with its commitment to adaptive capacity, relational sensitivity, and self-emptying — the difference between plan and life need not become a contradiction. Instead, representation can remain provisional and responsive, allowing the city to be continually re-made through the reciprocal shaping of vision and lived experience.

Lethaby: on art, community service, and “well-doing” = “We have to refound art on community service as the well-doing of what needs doing.” / civic life supplies bodily health and “spiritual refreshment,” and that art must be re-grounded in service to the community rather than ornament or display = “well-doing / sukṛta / Ṛta”

Negri: the common as the convergence of movements = “The common is nothing but all these movements conjoined.” / the ‘common’ = the convergence/coming-together of creative, social, and political movements [re. Gibson’s civic project (art + living + making) = Negri’s conception of the common as emergent, collective production rather than a static resource]

Negri: living labour / the general intellect = “…an immaterial, intellectual, linguistic, and cooperative workforce that corresponds to a new phase of productive development based on the excess of…living labour.” / living labour + the general intellect = contemporary, immaterial forms of production [re. Gibson’s integrated civic practice = living labour (designers, builders, citizens) = constituent power.

[Lethaby] / “we have to refound art on community service as the well-doing of what needs doing” = ethical-aesthetic = early twentieth-century civic reform (‘Town Theory and Practice’) -> [Negri] Gibson’s civic statement = political-ontological: the “well-making” of the city = living labour and participates in the construction of the common — “the common is nothing but all these movements conjoined” = art, planning and labour together enact constituent power rather than merely representing it / https://mediaecologiesresonate.wordpress.com/2008/10/27/on-the-work-of-art/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[Lethaby / primary text: ‘Town Theory and Practice’ (1921), chapter ‘The Town Itself’ / (searchable) https://archive.org/stream/towntheorypracti00purduoft/towntheorypracti00purduoft_djvu.txt]

[Negri / primary text: ‘The Porcelain Workshop: For a New Grammar of Politics (2008) (see Christian Lotz re. p.98 / p.67 / p.103) / https://christianlotz.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/lotz-movements-or-events-badiou-or-negri-2021.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Lethaby: ’The Builder’s Art and the Craftsman’, in ‘Architecture a Profession or an Art’, ed. R. N. Shaw and T. G. Jackson, 1892

p151 Architecture is the easy and expressive handling of materials in masterly experimental building—it is the craftsmen’s Drama.

p152 The architecture of the past…in regard to structure, was the evolution which was a necessary result of the immediate handling of materials; experiments in the placing and balancing of stones and the framing of timber; the result of direct drawing and painting with the workman!s tools as regards the outer texture and decoration.

pp152/153 Architecture was then not a superficial veneer, the supercilious trick and grimace of art, overlaid by building-barristers—the special pleaders of an organised and would-be privileged corporation—on the dreary work of drudges; it / was the construction of buildings done with such fine feeling for fitness, such ordinary traditional skill, selection, and insight, that the work was transformed into delight, and necessarily delighted others. Design was not the abstract exercise of a faculty plus a pair of compasses, nor even this faculty working on data of purpose, position, and proportion. It was insight as to the capabilities of material for expression when submitted to certain forms of handiwork. It was the imaginative foresight which came of the designer’s experience of his former results, when the subject, as Charles Lamb says, has so acted that it has seemed to direct him —not to be arranged by him—so tyrannically that he dare not treat it otherwise, lest he should falsify a revelation.’

p154 …when you fairly begin to consider how best to deal with stone as a material you have begun then first to free yourself from the bonds of mere academic architecture.

pp156/157 I am perfectly certain that a vast amount of very beautiful buildings that are built all over the country never had an architect at all, but the roughest possible draft was made out for these buildings, and they grew up without any intermediary between the mind and the hands of the people who actually built them. No doubt the great reason that was so was because the people who built them were traditionally acquainted with the best means of using the material, which happily for them they were forced to use—the materials that were all around them in the fields and woods amidst which they passed their lives. What is true of the wall is equally true of the roof. The traditional knowledge of local material, the general harmony, almost as of nature’s own, when the material of the country-side is used, the craft of gathering these materials, and the art of using them, is submerged in the universal deluge of dreary machine stamped tiles, or Welsh slate, ‘as specified’ by the office-bred architect. It is but a day since that I was told of a thatcher who knows his craft well, not only in the plain parts, but all the devices and embroideries for hips and ridges in what is pre-eminently the Saxon roof—’He is the only good thatcher left.’

p158 …modern plaster is quite unfit for work of this sort; the old material was washed, beaten, stirred, and tested so carefully, and for so long a time, that when laid it was, my informant said, ‘as tough as leather’.

p159 It is to be noted that these things have not changed because of a change in man’s nature; wherever handicraft has not been intercepted from material by the intervention of a learned profession, work is still as perfectly beautiful as ever it was, be it in the windmills of the millwright, the fishing smacks of the ship-wright, or the wains of the waggon-builder, romantic with quaint chamferings, gay with bright paint.

p161 In those things beyond mere building, ‘through which he may show his affections and delights,’ the converse of this is equally true: it is impossible for a man really to design except through the material in which a work is to be executed and according to the exact skill of the executant. No man (except by suggestion) in these things can design for other than himself. Design progresses and changes through the suggestions gained from direct observation of special aptitudes and limitations in material, and the instant ability to seize on a fortunate accident, and to know when the work is properly finished. The separation of the two necessarily makes design doctrinaire, a hotpressed-paper-craft,—and workmanship servile; degrading even in the ordinary necessities of building, destructive to ornamentation; a mere insult and pretence of art at which sculptors and painters do well to make a mock.

[p169 …it is impossible that ‘design,’ as taught by professors for the purposes of an examination on paper, can be anything other than a classification of past art; it cannot be otherwise than that ‘design’ so learnt shall be as dull as the lectures in courses, which profess to tell exactly how it all once happened, but do not attempt to say why it does not happen now. / Such designs by such superior persons will never solve the problems of actual work; work will solve all the problems of design. At present we are trying to paint our picture by means of measurements and written directions, to do our sculpture by detail drawings, and all by lowest tender; is it any wonder that we fail?]

[Lethaby: ‘The Builder’s Art and the Craftsman’] handling of materials + experimental building = beneficial practice = developing adaptive capacity, relational sensitivity, and self-emptying

- ‘handling of materials’ / embodied, tactile engagement with material / the physical world = continuous responsiveness to the affordances, limitations, and behaviours of different materials = adaptive capacity / sensitivity to subtle variations leads to an openness and flexibility = relational sensitivity = attunement to context, otherness, and process.

- ‘experimental building’ / learning through doing, iterating = possibilities + experimentation = self-emptying / challenges preconceptions / no fixed outcomes / open to emergent forms / discovery over rigid planning = meditative or reflective modes of practice = presence and co-arising.

- ‘beneficial practices’ = transformative relationality between practitioner, materials, environment, and outcome.

[Negri] living labour = the active, creative human labor -> produces value, knowledge, and culture — not just physical goods / ‘general intellect’ -> the collective, social knowledge embedded in the worker’s mind, the tools, and increasingly, in digital and immaterial forms.

[Lethaby] handling of materials and experimental building = prefigurative practices of living labour: embodied, creative, and adaptive forms of work that resist rigid industrial standardisation = practices foster skills, sensibilities, and knowledge that are socially distributed (relational) and continually renewed (experimental).

[contemporary immaterial production = knowledge work, digital design, social collaboration] -> [Lethaby] = grounding in embodied, situated, and relational activity rather than abstract or alienated labour / challenges the disembodiment often associated with immaterial production by insisting on attentiveness and experimentation in making.

Lethaby’s ideas re-anchor Negri’s concepts in the materiality of practice / a bridge between physical engagement and digital/immaterial creativity = how adaptive capacity and relational sensitivity = vitality of living labour in all forms.

Lethaby as beneficial practice = adaptive, relational, and open = conceptual and practical grounding for Negri = living labour and general intellect = re-centring creativity and knowledge in embodied, material engagement [as forms of production evolve toward immaterial] the materiality of practice = vital grounding—the way even the most abstract creativity is anchored in embodied, tactile, and relational engagement / knowledge and labour emerge through doing in the world, not just in the head or the cloud = head in the clouds = daydreaming or absentminded or impractical/unrealistic or disconnected.

W. R. Lethaby: ‘The Builder’s Art and the Craftsman’ (1892) / “expressive handling of materials in masterly experimental building” / critiques formal, desk-bound design / “the separation in the building of design and workmanship”

Lethaby & Gibson: material process as foundational to architectural education = the materiality of practice = Lethaby = “Expressive handling of materials in masterly experimental building” / material experimentation / rejects purely theoretical or superficial design approaches / Gibson = [Liverpool School of Architecture] “learn to handle and work on materials in the early years” / emphasis into pedagogy—structuring curriculum to ensure students learn through tactile, material-based making from the outset.

Causal chain:

Lethaby -> (Central School, School of Building) national pedagogical model (Central School, emphasis on craft + experiment) / “experimental building research in materials and structures” -> wider reception (Muthesius, debates about technical vs. artistic training) -> local adaptations (Liverpool School = draughtsmanship / C. H. Reilly vsGibson’s Materials Gallery) = Gibson -> material-first impulse + Bauhaus/modernist ideas re.integrating technical, architectural and planning training / “Bauhaus-inspired” school model = the Materials Gallery = national pedagogic shift

[Note: Victor Pasmore / ‘Basic Design’ / “In the art schools of the 1950s in Britain, Basic Design emerged as a radical new artistic training. It emerged in response to already-existing teaching methods embodied within the skills-based National Diploma in Design and was the first attempt to create a formalised system of knowledge based on an anti-Romanticist, intuitive approach to art teaching. [. . .] was rooted in the German Bauhaus and its Vorkurs course, started by Johannes Itten (1888–1967) in the 1920s, a preliminary or foundation course that focused the art student’s attention on the manipulation and understanding of materials. Formal exercises were tempered by other much freer activities that aimed to develop students’ sense impressions of the world around them through nature studies and new forms of life drawing.” [Tate Britain, 25 March – 25 September 2013] https://www.tate.org.uk/documents/1418/basic_design_booklet.pdf]

[“The…atmosphere of a place is where the mysteries of the trade become no mysteries, they are as it were in the air [and] children learn many of them unconsciously” [Alfred Marshall, ‘Principles of Economics’, 1890]

[a proto-beneficial practice / where presence, adaptation, and relational sensitivity / learned in situ]

It binds materiality, community, and knowledge practice within a living context.

[bridges]

Ecclesiastes 9:10

“Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might, for in the realm of the dead, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom.”

This verse grounds labour in total commitment — not in abstract achievement or in separation from the body, but in the act itself = beneficial practice: the doing is the transformation, and the intensity of attention is itself adaptive capacity and relational sensitivity.

The Hands — Fernand Léger (1951)

‘The Hands, Homage to Mayakovsky’ = manual labour as a site of creativity, solidarity, and political vitality.

The hands are rendered monumental — not delicate — stressing agency, capability, and material engagement.

By linking the work to Mayakovsky, Léger situates manual work in revolutionary poetics — a perfect echo of Negri’s vision of living labour as socially constitutive and collectively intelligent.

A post-War, machine-age modernist bridging between the artisan ethos of Lethaby and the collective industrial/social energy of Negri.

The image shows two side-by-side screenshots taken using Google Lens. Each one depicts a collage-like black and white artwork overlaid with detected/translated text. Constructivist visual language collage as a political statement about labor, automation, and the erasure or transformation of human identity through work.

version #4

their tools resembling hands Their / hand lathe tools / pants with when / fold their pants A mountains / on Sunday Has at / he will free himself, it’s abstract THEY DO That / to his wife, to his daughter / is chic MEMORY of / LOOK ALIKE / to those of their / he is disgusting / of the prelate once a week. / As long as / machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot not / demolished, built, very hight / are approaching very low, under the water in the sky the marching EVERYWHERE in this world THEIR HANDS FOR THEM Are presented Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS Why NOT? hopefully there will be gloves / WHY NOT? / ITS / PLANT / West on the road / Starts Today

version #5

tools Raising hands look like To Their tools in their hands pants are / when euro / my not fold there / folds on Sunday has mountains in slices he will break free, it’s abstract THEY DO / to his wife, to his daughter once a week / is classy. MEMORY of LOOK ALIKE / to those of their / he is disgusting… As long as / machine His hands are heavy! in his arms there / a lot / demolished, built, very high very low, under water In the sky EVERYWHERE Damn the world THEIR HANDS are the marching For them Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS PRESENT Why not? / he will have gloves. WHY NOT? / HIS FACTORY / he is on the road / Starts Today

version #6

their tools look alike Their hands Their tools in their hands When maps their pants a pan unfold / on Sunday mountains at very many trees he frees himself, it’s abstract / to his wife, to his daughter THEY DO / once a week. / LOOK ALIKE NOT TO THE I have her concierge. / is chic. MEMORY to those of their / he is disgusting… / of the / As long as / machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot / demolished, built, very high are approaching very low, underwater in the sky the marching Around the world THEIR HANDS For Are THEM Then he will also have PRESENT hands like HIS BOSS WHY NOT? anyway he will have gloves. FOR / ITS FACTORY / IT Approaching ballast on the road / begins Today

— — —

Lethaby: insists on material practice, experimental making, and learning through direct handling — a pedagogy of presence and attunement.

Negri: foregrounds the social, cognitive, and cooperative dimensions of production — a politics of shared intellect and potential.

Ecclesiastes 9:10 + Léger’s ‘The Hands, Homage to Mayakovsky’ = labour as embodiment and socialisation:

- materiality of practice = living labour stays grounded in presence.

- beneficial practice = developing adaptive, relational capacities.

- general intellect = presence as networked, collective field.

Alfred Marshall’s ‘Principles of Economics’ (1890) https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/economics/marshall/bk4ch10.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

How skills and sensibilities become part of a place’s atmosphere:

“When an industry has thus chosen a locality for itself, it is likely to stay there long: so great are the advantages which people following the same skilled trade get from neighbourhood to one another. The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are as it were in the air, and children learn many of them unconsciously. Good work is rightly appreciated, inventions and improvements … are promptly discussed: if one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own …”

Ambient Learning & Beneficial Practice | The Quick & The Dead, Birmingham, 2011

Marshall’s “in the air” metaphor captures tacit knowledge — the ambient transmission of skill, sensibility, and tacit knowledge — what’s “in the air” when a craft, a trade, or a form of labour is practiced collectively in a place / skills absorbed not through instruction, but through the atmosphere of doing -> beneficial practice, where capacities (adaptive, relational, emptying) arise through immersion, not abstraction.

“practiced collectively in a place” + “tacit knowledge”

‘frame this tension not as a contradiction but as a dialectic of labour’s embodiment and socialisation’

Lethaby: materiality and direct handling.

Negri: collective intelligence — the general intellect — here, almost literally the shared, invisible knowledge in the air

Marshall: the place-bound atmosphere where embodied doing and social learning dissolve into each other, making the mysteries common property without formal codification.

Just as Ecclesiastes reminded us of embodied labour’s moral presence, Marshall grounds it in ecology — a shared, generational, spatial learning environment. It binds materiality, community, and knowledge practice within a living context.

[note: John Panting, see below] “…to attend to the nature of spatial relationships, their manipulation and the nature of their construction and perception – movement analysed in terms of sequence – qualities of weight, substance, an occasion to examine sequences of construction / manipulation – problem to divest material of associative meaning – avoiding begging questions of meaning in material terms – presentation of perceptual configurations that function in terms of their relationships – eschewing alternative literary, structural or mathematical interpretation.” – John Panting, undated

[ref file: John Panting | Guenther & Ontopoetics]

24.04.2020 Remade Drawing

“There is no attempt to abridge the apparent redundancy with a sense of tacit order. The usual checks and balances are conspicuously absent.” [text: Ronnie Rees, 1975]

— — —

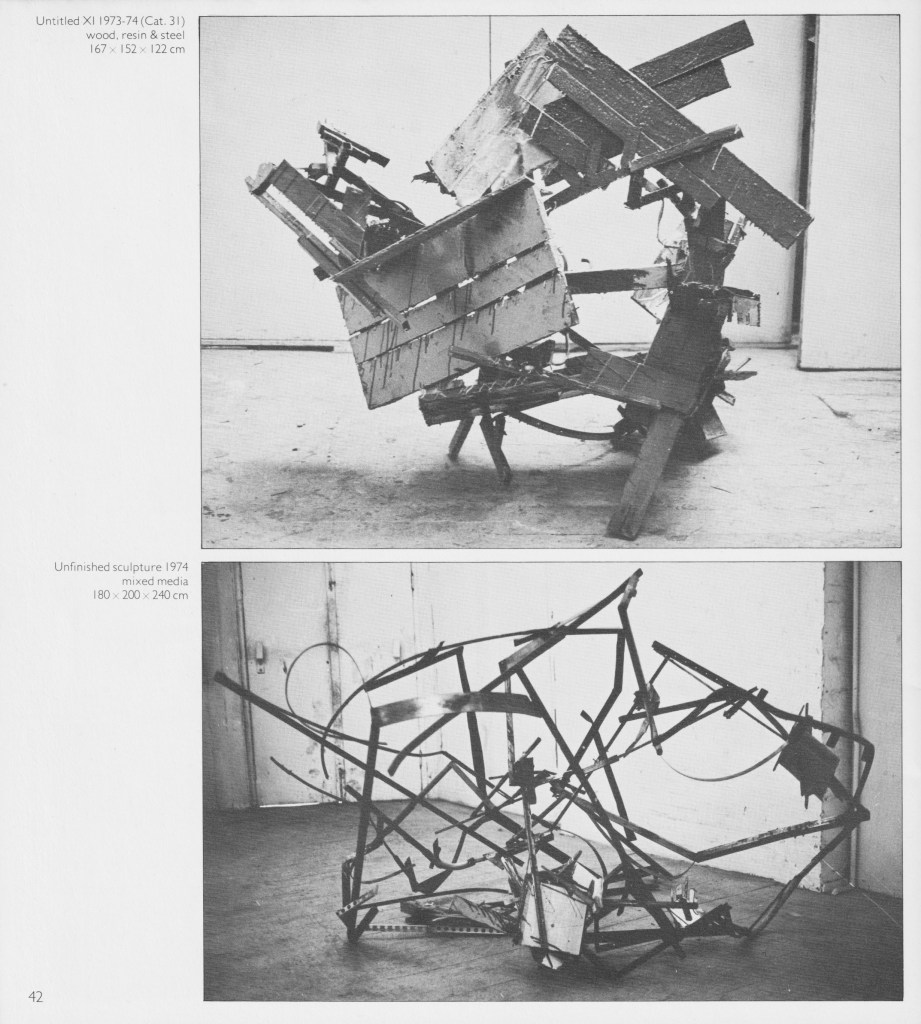

…a non-dual, poetic unfolding of perception / matter rising into awareness, not as object, but as gesture of becoming. These are sculpture as awareness, matter-worlds in poetic suspension:

- fragmented assemblages of wood, resin, steel, and mixed media

- angular, precarious, and materially stressed

- characterised by exposure of structure, absence of enclosure, and a tension between collapse and emergence

- built from ruptured planes and skeletal geometries, as if caught mid-formation or mid-dissolution.

These are not objects that aim for completion, but rather processual intensities—sculptural acts of becoming.

| Guenther [Dzogchen] | Sculptural Expression |

| thol.skyes.kyi.rig (free-rising) | Emergent, ungrounded structures; no centre, no hierarchy |

| sgyu.ma.lta.bu (phantom-like) | Apparitional, incomplete; presence as unstable echo |

| yuganaddha (bliss + emptiness) | Joy in brokenness; the radiance of unfinished forms |

| mthum.mon.ma.yin.pa (non-totality) | Refusal of system; composition as infinite relation |

| ontopoiesis | Form as poetic event; material as trace of perceptual arising |

Ontopoetic Analysis

1. Free-Rising Perception (thol.skyes.kyi.rig) -> Forming Without Ground

Guenther’s idea of free-rising perception describes a cognition that arises without fixed base—not Samsara, not Nirvana, but luminous presence emerging unbidden. These sculptures enact that same non-foundational emergence:

- No clear centre of mass or symbolic axis

- Assemblage as spontaneous structural gesture, not representation

- Forms rise into space without architectural finality

Ontopoetically: These are material metaphors of perception itself, rising without premise—like a thought unfurling into matter.

2. Phantom-like Tableau (sgyu.ma.lta.bu) -> Vision-as-Evanescence

Guenther’s use of the term phantom-like tableau refers to the world seen as both vividly present and fundamentally unreal—like a dream or mirage. These works hover in that paradox:

- Heavily built yet impossible to read as stable form

- Appear as ruins or speculative machines, not things with clear functions

- They suggest an ontological condition: being as flickering apparition

Ontopoetically: They are worlds glimpsed, not grasped—structures in the midst of unmaking, speaking to the instability of all fixed meaning.

3. Yuganaddha (Bliss + Emptiness) -> Joy in the Gap

Despite their precariousness, there’s a visceral joy in their facture:

- The drips, welds, and joins are left raw, celebrating the process of emergence

- Their emptiness is not lack, but openness—spaces for resonance, light, air

- Bliss and śūnyatā are not opposites, but conjoined conditions of being

Ontopoetically: These sculptures are the bliss of form unfixing itself, of poiesis as refusal of closure.

4. mthum.mon.ma.yin.pa -> Non-Totalizing Composition

This Tibetan term describes a non-systematic, open-ended form of meditation—one that doesn’t unify or conclude. These works refuse totality:

- No “whole” to be seen—only a shifting array of relational tensions

- They don’t “resolve”—they reside in a continual threshold state

- The viewer must dwell with them, rather than interpret them

Ontopoetically: These are non-teleological forms—not arriving, but continuously arriving. They model attentiveness rather than assertion.

5. Ontopoiesis of Form -> Material as Event

Guenther’s radical reinterpretation of perception suggests that form is not representation but the arising of awareness itself. These sculptures enact:

- Perception externalised into material gesture

- Form not as product, but as trace of encounter

- The making and unmaking held visibly in tension.

— — —

John Panting | Serpentine Text 1975

John Panting as beneficial practice: skilling and de-skilling, secular self-emptying, relational sensitivity, transformative embodied practice, and the tension between representation and lived experience.

1. Intention and ethical stance

Panting is remembered above all for his honesty, generosity, and his refusal to impose rigid dogmas on students or colleagues. His authority came from “quiet calm and reasoned authority” (Clatworthy) and his commitment to “keeping discussions open-ended” (Jones). This aligns strongly with the ethical orientation in beneficial practice: his teaching and leadership were not about fixed positions but about holding open a field where others could act and think.

2. Skilling and de-skilling

His facility with materials was remarkable — “cool ease and prodigious speed” (Pye) — yet it provoked his own self-doubt, pushing him to question and disrupt his own facility.

From the cable works of 1971 through the geometric Italian sculptures, and finally to the radical improvisations of 1973–74, his trajectory was one of deliberate violation of prior assumptions. Rees describes him as “thwart[ing] his own taste and facility” and ensuring “constraints and formal conditions… were invariably violated.”

This is pure de-skilling/re-skilling: the refusal to rest in comfort, the embrace of risk, the search for new perceptual and material vocabularies.

3. Secular self-emptying

Panting’s scepticism toward his own achievements, his refusal to say definitively what he liked (Pye), and his constant openness to contradiction and plurality of arguments are forms of self-emptying. He undercut his ego as “the artist” by never settling on a fixed self-image, instead allowing work, dialogue, and contradiction to unsettle identity.

4. Relational practice

His pedagogy blurred the line between teaching and life (Jones): discussions flowed into meals, work into dialogue, art into existence. He organised studio time with staff and students together, breaking down hierarchies of position. His manner of speaking — “slow and deliberate… a pace for sculpture and not for everyday things” — turned conversation itself into a medium of practice. This is beneficial practice as relational becoming.

5. Transformative embodied process

Panting’s late works especially embody the transformative arc: improvisational, raw, immediate, deliberately contradictory, demanding attention, “remarkably free and open” (Rees). His work is not just representational but experiential, asking the viewer to enter into flux and instability — exactly the perceptual re-skilling we’ve been tracing from Cubism through Newman.

Synthesis #1 (paragraph)

John Panting’s career can be understood as a vivid enactment of beneficial practice. His extraordinary facility with materials became, paradoxically, the spur for continual de-skilling and re-skilling: he deliberately violated his own taste and technique in order to keep sculpture alive as an inventive, open-ended medium. This refusal to settle was underpinned by a profound self-emptying — an uncompromising honesty, scepticism about his own achievements, and a commitment to plurality rather than dogma. In both teaching and leadership, Panting embodied relational sensitivity: blurring the line between life and pedagogy, opening dialogue as a shared sculptural space, and fostering co-creation across hierarchies. His late works, raw, improvisational, and contradictory, testify to a transformative embodied process in which sculpture was continually re-invented, not as a perfected object but as an evolving field of attention and relation. In this sense, Panting’s brief career affirms that beneficial practice is not about mastery but about the generative tension between skill and doubt, expression and restraint, self and other, always oriented toward the well-doing of what needs doing. [16.08.2025]

[from Ronnie Rees, 1974] the exigencies of physical pressure / less deliberate and more casual / reticence and deliberation / a more open-ended and speculative approach / broken and irregular / complexity is surprising / no attempt to abridge the apparent redundancy with a sense of tacit order / usual formal checks and balances are conspicuously absent / free and open / raw and immediate / independence / challenging his expectations / diversity and vigour / strength and conviction / improvise / aligning materials and techniques in eccentric conjunction / to thwart / Nothing apparently was to be taken for granted / instinct for the richness / merge disparities and encourage contradiction / prior assumptions / invariably violated / continually invented / eloquent fulfilment and success

Each phrase registers a refusal of closure, an openness to process, and a readiness to let form arise from relational forces rather than from pre-given templates.

1. Material pressure and responsiveness

- “the exigencies of physical pressure”

- “less deliberate and more casual”

Here the work acknowledges the agency of matter and process: sculpture arises from conditions rather than imposed will. Beneficial practice is revealed as adaptive capacity — allowing the world’s pressures to shape outcomes.

2. Oscillations of control and release

- “reticence and deliberation”

- “a more open-ended and speculative approach”

Panting moves between self-restraint and risk-taking. Beneficial practice is not fixed at one pole but learns to inhabit the rhythm between control and openness.

3. Complexity, contradiction, and refusal of order

- “broken and irregular”

- “complexity is surprising”

- “no attempt to abridge the apparent redundancy with a sense of tacit order”

- “usual formal checks and balances are conspicuously absent”

These phrases point to a conscious refusal of neatness. Beneficial practice here is anti-reductive: it accepts messiness and contradiction as necessary conditions for transformation.

4. Rawness, immediacy, freedom

- “free and open”

- “raw and immediate”

- “independence”

The emphasis shifts from polished completion to experiential force. Beneficial practice takes form as presence, prioritising direct encounter over perfected representation.

5. Self-disruption and re-skilling

- “challenging his expectations”

- “diversity and vigour”

- “strength and conviction”

- “improvise”

- “aligning materials and techniques in eccentric conjunction”

- “to thwart”

- “Nothing apparently was to be taken for granted”

This is the heart of beneficial practice as de-skilling/re-skilling: deliberately interrupting habit, courting eccentricity, and refusing complacency. Self-emptying enables new skills to emerge.

6. Affirmation through contradiction

- “instinct for the richness”

- “merge disparities and encourage contradiction”

- “prior assumptions … invariably violated”

- “continually invented”

- “eloquent fulfilment and success”

Ontological weight = invention through violation, richness through contradiction, eloquence through continual becoming. Beneficial practice is not resolution but transformative tension.

Synthesis #2

Beneficial practice = a process that responds to material pressures while holding open speculation / that resists neat order in favour of raw immediacy / that continually disrupts prior assumptions through improvisation and contradiction / that achieves eloquence not by closure but by perpetual reinvention. [John Panting] “pressure,” “irregularity,” “contradiction,” + “continual invention” = embodied ethics of beneficial practice as purposeful, flexible, and responsive = an art of tension and openness as the conditions of transformation.

— — —

Worktops 2025 | Text: “the shrieking condemnation, by the tearing gesture itself, of any authorial posturing | artistic agency / what does it mean to be an artistic subject, an author”

Text: “ordinary techniques produced a fragile, improvised object / the selection and inventive manipulation of unlikely, preformed elements / physical (nontranscendent) acts such as cutting and folding paper substitute for traditional drawing / subvert / exchange of the codes of painting and sculpture / a mingling of optical and haptic modes / in the gap between de-skilled labour (which might be carried out by anyone) and highly skilled, “immaterial” labour that preserves a sense of artistic spontaneity in its messy, inefficient facture.”

…a stack of art papers or sketchbook pages, likely from an artist’s studio or personal archive / informal and process-oriented, suggesting a work-in-progress or archival collection of creative experiments / paint smudges and creases imply it was used practically, not preserved for presentation / studio practice — informal, raw, and rich with process / [evoking] the gestural, intuitive aspects of art-making / a process archive, sketch dump, or a “working pile” that reflects thinking-through-doing / traces of gesture, decision, and experimentation / remnants or tools of making / not a single artwork.

21.06.2025 | Summary of two texts:

The work resists traditional structure and coherence, favouring an informal, process-driven approach where conventional order and artistic hierarchy are absent. Instead, it embraces a raw, experimental mode of creation using everyday materials and actions—cutting, folding, stacking—blurring boundaries between painting and sculpture, skilled and unskilled labour, and finished and unfinished states. It becomes a record of gesture, thought, and making—a provisional archive of spontaneous, physical experimentation rather than a resolved, singular artwork.

— — —

Note: Ronald (Ronnie) James Rees, b. 20.11.1945 Kilmarnock / d. Q4 2002 Tower Hamlets, London, lived (1970s & 1980s) flat & studio near Old Street, London.

[Xmas Term 1974/75: Ronnie asked me for my lighter and I gave him my new girlfriend’s new Bic disposable lighter [https://www.moma.org/collection/works/90084], and rolled a cigarette — please that I could smoke while he reviewed the paintings I had made during the summer vacation. He said he liked what I had done, but that it would be better like ‘this’ and promptly hurled my new girlfriend’s new Bic disposable lighter at the wall where it shattered on impact. It was a great piece of teaching which I only really began to understand a year later when looking at two of John Painting’s late sculptures in the Serpentine Gallery and reading Ronnie’s catalogue comment: “There is no attempt to abridge the apparent redundancy with a sense of tacit order. The usual checks and balances are conspicuously absent.”]

“There is no attempt to abridge the apparent redundancy with a sense of tacit order. The usual checks and balances are conspicuously absent.”

[Ronnie’s contribution to the catalogue for the Serpentine Gallery’s 1975 John Panting retrospective was taken from a longer article he had written for the September 1974 issue of Studio International. This had been written to mark Panting’s death in a motorbike accident in July 1974 at the age of 34. Besides being my 3rd Year tutor at Birmingham School of Art & Design, Ronnie had taught with John Panting at Central School of Art & Design, and was part of “the anarchic golden age of British art schools” that bridged regional art school traditions with larger national or international movements. Ronnie had been included in the British Painting ’74 (Gallery 1) at the Hayward Gallery, 26 September to 17 November 1974, and was later named in the list of “close friends” in art critic Tim Hilton’s obituary [Guardian, 31.01.2024] along with Gillian Ayres, Terry Atkinson, Michael Bennett, Anthony Caro, Barrie Cook, Barry Flanagan, John McLean…and John Walker.”]

The 1974 Studio International article and 1975 Serpentine Gallery full catalogue texts can be found below.

— — —

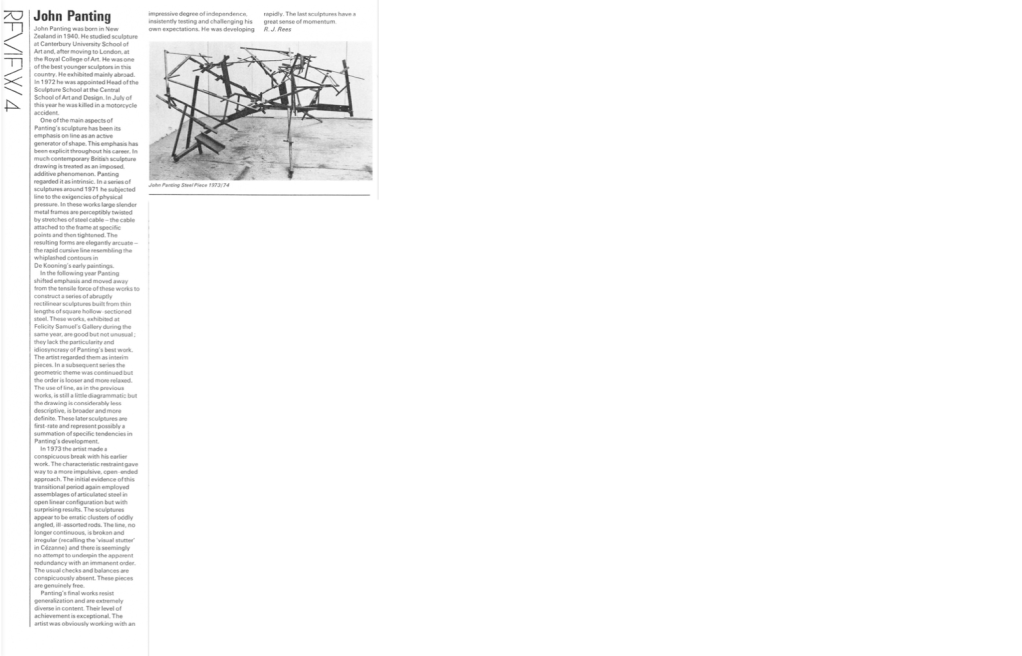

1974 Studio International | REVIEW 4 | John Panting / R. J. Ress

John Panting was born in New Zealand in 1940. He studied sculpture at Canterbury University School of Art and, after moving to London, at the Royal College of Art. He was one of the best younger sculptors in this country. He exhibited mainly abroad. In 1972 he was appointed Head of the Sculpture School at the Central School of Art and Design. In July of this year he was killed in a motorcycle accident.

One of the main aspects of Panting’s sculpture has been its emphasis on line as an active generator of shape. This emphasis has been explicit throughout his career. In much contemporary British sculpture drawing is treated as an imposed, additive phenomenon. Panting regarded it as intrinsic. In a series of sculptures around 1971 he subjected line to the exigencies of physical pressure. In these works large slender metal frames are perceptibly twisted by stretches of steel cable — the cable attached to the frame at specific points and then tightened. The resulting forms are elegantly arcuate — the rapid cursive line resembling the whiplashed contours in De Kooning’s early paintings.

In the following year Panting shifted emphasis and moved away from the tensile force of these works to construct a series of abruptly rectilinear sculptures built from thin lengths of square hollow-sectioned steel. These works, exhibited at Felicity Samuel’s Gallery during the same year, are good but not unusual; they lack the particularity and idiosyncrasy of Panting’s best work. The artist regarded them as interim pieces. In a subsequent series the geometric theme was continued but the order is looser and more relaxed. The use of line, as in the previous works, is still a little diagrammatic but the drawing is considerably less descriptive, is broader and more definite. These later sculptures are first-rate and represent possibly a summation of specific tendencies in Panting’s development.

In 1973 the artist made a conspicuous break with his earlier work. The characteristic restraint gave way to a more impulsive, open-ended approach. The initial evidence of this transitional period again employed assemblages of articulated steel in open linear configuration but with surprising results. The sculptures appear to be erratic clusters of oddly angled, ill-assorted rods. The line, no longer continuous, is broken and irregular (recalling the ‘visual stutter’ in Cezanne) and there is seemingly no attempt to underpin the apparent redundancy with an immanent order. The usual checks and balances are conspicuously absent. These pieces are genuinely free.

Panting’s final works resist generalization and are extremely diverse in content. Their level of achievement is exceptional. The artist was obviously working with an

[break]

impressive degree of independence, insistently testing and challenging own expectations. He was developing

[break]

rapidly. The last sculptures have a great sense of momentum.

R. J. Rees

— — —

1975 Serpentine Gallery | Catalogue Texts

JOHN PANTING 1940-1974

SCULPTURE

2-28 September 1975

Serpentine Gallery, Kensington Gardens. W.2.

Arts Council of Great Britain

Catalogue published in association with the Queen Elizabeth Il Arts Council of New Zealand

JOHN PANTING

1940-1974

SCULPTOR AND TEACHER

John Panting, one of the most promising of the younger sculptors to have emerged during the 1960s, died in a road accident on July 31. Born in New Zealand in 1940 and moving to London in 1963, he studied at the Royal College of Art from 1964 to 1967 where he was an outstanding student. At the end of his course, he became a tutor at the Royal College, also teaching in a part-time capacity at a number of other art schools. In 1972 he was appointed as the Head of the Sculpture School at the Central School of Art and Design and during the tragically brief time he served there, his remarkable qualities of judgment, energy and concern for his responsibilities made him a major figure in the development of the school. His own sculpture is comparatively little known here, except among the discerning few, for he had exhibited more widely abroad, notably in Italy, Holland and Switzerland.

As a man and a friend, what most impressed—and it was a quality that he possessed from his student days—was a manner of speaking with a quiet calm and reasoned authority, immediately recognized and respected by all who met him. This led to his opinion being much sought after by his peers and students alike.

He was uncompromisingly honest and generous in all his dealings.

Robert Clatworthy

The Times Obituary August 10th 1974

John made sculpture from 1958 until 1974. He worked continuously and compulsively. This exhibition shows a very small sample of his work, completed between 1965 and 1974. It is not selected as the best, nor is it neatly representative. It is simply what was available. The photographs give some sense of the body of his work and a clue to the continuing concerns which inhabit it. All John’s work requires attention; here we have many pieces ranging widely in form and technique and shown in the simplest chronological groupings, unrelieved by theme, title or apologia. It follows that the show is demanding and it must be so.

There is something else too to be taken into account, and that is that it has been put together by his contemporaries-other artists, with Arts Council support, out of a shared conviction that his was a major talent, that this work is of the highest quality: that it is necessary.

Steve Furlonger

That summer holiday period when a handful of students had the sculpture studios to themselves used to be the most precious working time of the year while I was at the Royal College of Art, when the sense of an institution was least evident, and the atmosphere of a professional studio prevailed. It was at this time of the year that I first met John Panting, who had just arrived from New Zealand and immediately set to work with a commitment and energy that his friends soon came to take for granted.

He revealed his talents unobtrusively, being a man of obsessive modesty, so that one was continually discovering new facets of his personality, his extensive reading, or extraordinary knowledge of music. Characteristic of him was the pleasure he derived from his fellow human beings, and the marvellously convoluted turn of phrase which often seemed like self-parody. His control and understanding of materials, his craftsmanship, was outstanding

This was not demonstrated by feats of virtuosity, but more by the cool ease and prodigious speed with which he worked: but always with an almost casual air, never a sign of struggle or panic. Added to this was an unusual physical stamina he could survive long periods with very little sleep and the combination of these attributes resulted in an enormous output of work. However, the easygoing, almost relaxed, demeanour may have belied the true nature of his obsessiveness to those who did not know him well. His was a disruptive and self-questioning talent, and I believe it was the very facility with which he could make things which caused him to question and doubt so harshly what he did. He was well-informed, thriving on the exchange of ideas and conflicting opinions, particularly within the art school ambience of fellow artists and students, where he was greatly respected. Something we will all miss is listening to John exercising his ability to argue three or four different points of view all at the same time with perfect balance and emphasis, the arguments always under control. For John to say definitively what he liked was quite out of character, an unfashionable trait in these rather doctrinaire times; he was committed to keeping that type of question an open one although under constant scrutiny. This was not simply due to the natural doubt of the intellectual (he was certainly not indecisive), but because there was a real conflict within him. He was a sensualist whose sculptural gifts offered a natural outlet of self-expression. One cannot overlook the exultation that emanates from some of his beautifully made pieces, whether they are made of fibreglass, steel or wood. However, an ascetic side of his nature caused him to suspect expressions of sensuality as an unacceptable indulgence. I feel it is this dichotomy within the work that gives the real cutting edge to the extraordinary range of the sculpture he produced over the last decade.

William Pye

July 1975

I won’t presume to know John Panting. Though we were contemporaries at the RCA Sculpture School it was not until I began teaching at the Central School of Art where he was Principal Lecturer in Sculpture, that some form of dialogue occurred.

It is true to say that when he took over the Sculpture Department in 1972 it was down at heel He was the only full-time member of staff in the department, but his enormous energy coupled with a much underrated capacity to co-operate with people with whom he disagreed, made for a department that was ambitious and polemical. John Panting’s determination to establish not only a better Sculpture Department but, more broadly the best Fine Art Department, meant that he was prepared to break rules; his ability to convince people of its necessity, to ‘flannel’ occasionally, resulted in his usually obtaining his wishes with little or no acrimony. He began to accept too many students and employ too many staff for the department’s designated size. “Doing is the quickest answer” might be said to have been his strategy as an executive; “it is much easier to justify something already established than to hypothesise”. In this context he was an assuming person and as a corollary the part-time staff were insulated from the pressure placed on their employment from outside the department.

The improvement of the department required a good deal of planning and, having assembled a group of staff around him with diverse interests, there was much discussion. In complete contradiction to his executive role, as a teacher John Panting did not impose a prevailing attitude, and the discussions were generalised and unpragmatic. I remember feeling continually irritated that he refused to draw conclusions from these meetings. But then this was only the beginning and no-one, least of all John, wanted to adopt the first agreement between the staff as a basis of policy for the department. He wanted to keep the discussions open-ended; there was plenty of time.

Where I would demarcate as clearly as I could the line between teaching and my own life, John Panting would seek to blur that line with easy intensity. The established breaks for lunch became increasingly lost: clocks and watches were obviously regarded as insensitive bastards. Lunch could start early or late, could consume the whole afternoon or not take place at all because of reasons ranging from dialogue with students to dieting.

There was less compliance with hours contracted than with any other member of full-time staff with whom I have worked; to the department’s gain. The arrangement seemed to be, arrive on time and leave according to the matters of the day, be that early or late.

John Panting was a very impatient person. One would expect impatience to manifest itself in a hasty demeanour, and yet he was deceptively leisurely. I say this because the pace at which he worked was augmented by the extraordinary duration of his working day. He spent an enormous amount of time in his studio, often working there in the morning before attending the Central, and then returning after school sometimes to work all night. His commitment at the Central was not as a pedagogue but as an artist, and to this end he organised periods of time during the course when students worked in the studios of the staff and other artists. His approach to teaching was reliant on both his own presence and the duration of that presence. There was no prescribed pedagogical theory though of course he had a stance, an identity as an artist, which he conveyed. He usually talked individually with students and though he initiated some group projects I felt he worked better on a one-to-one basis. Talking with students, and John certainly enjoyed talking (“words are audible contours of thought”) is a traditional posture in art schools. Where John was different was in the cadence of his speech. His delivery of words was slow and deliberate; the discussion assumed a sense of importance, a pace for sculpture and not for everyday things. As far as I could observe the students acquired as much from John Panting’s style of utterance as from its content.

Working with John Panting at the Central School of Art was not without its faults or prolixity, but here was an undeniable sense of optimism. The loss is not only of his person but of that potential future. It is this enigma that remains.

Gareth Jones

July 1975

One of the main aspects of John Panting’s sculpture has been its emphasis on linear drawing as an active generator of shape. This emphasis has been explicit throughout his career. A series of metal frame sculptures in 1971 subjected line to the exigencies of physical pressure. In these works taut stretches of steel cable perceptively twist the aligned frames into elegantly mobile arcuate forms the rapid cursive line recalling the whiplashed contours in De Kooning’s early paintings.

In 1972 Panting departed from the cable sculptures to construct a series of abruptly rectilinear structures. These were built from thin lengths of square hollow- sectioned steel. The line is descriptive, diagrammatic and somewhat idealized. A subsequent series of works, shown in Italy, is similarly geometric but is less deliberate and more casual. These ‘Italian sculptures represent possibly the summation of the artist’s earlier stylistic concerns.

In 1973 Panting made a significant break with his earlier work. The reticence and deliberation which had characterized much of the previous sculpture gave way to a more open-ended and speculative approach. The initial sculptures which grew out of this transitional period are essentially compilations of broken and irregular rods articulated in short, repeated and opposed configurations. The complexity is surprising. There is no attempt to abridge the apparent redundancy with a sense of tacit order. The usual formal checks and balances are conspicuously absent. The sculptures are remarkably free and open and their sensation is raw and immediate During this latter period Panting began to work with an impressive degree of independence, insistently testing and challenging his expectations. The diversity and vigour of the later sculptures attest to a new source of strength and conviction in the artist. He began to improvise random and anomalous structures by aligning materials and techniques in eccentric conjunction in order to thwart his own taste and facility. Nothing apparently was to be taken for granted. His instinct for the richness of sculpture led him to merge disparities and encourage contradiction Constraints and formal conditions which brought prior assumptions to the work were invariably violated. Sculpture, for Panting, was an expressive medium which had to be continually invented. The explicit force and vitality of the late sculptures indicate the eloquent fulfilment and success of this ambition.

R. J. Rees