“…and the place of artists will have been reclaimed.”

Artists of Place | Place-Responsive Art

“A place comes into art loaded with content. An artist comes to a place in one of two ways: either loaded with content or, like a clean slate, ready to receive, interpret and represent what is already there. If the former, an artist will displace the resident meanings of a place with his preconceptions about art. If the latter, she will make those meanings visible as if for the first time. In so doing she may also make something that bears little resemblance to art; it may look like beach furniture, feel like a walking tour, read like an ethnic community library, sound like oral history, pass by like a parade or be organised like a photography competition. Having being made by an artist, however, it will be none of those things alone.”

– Jeff Kelley: Keynote Address, ‘Public Art — The New Agenda’ (conference), The University of Westminster, 18 November 1993

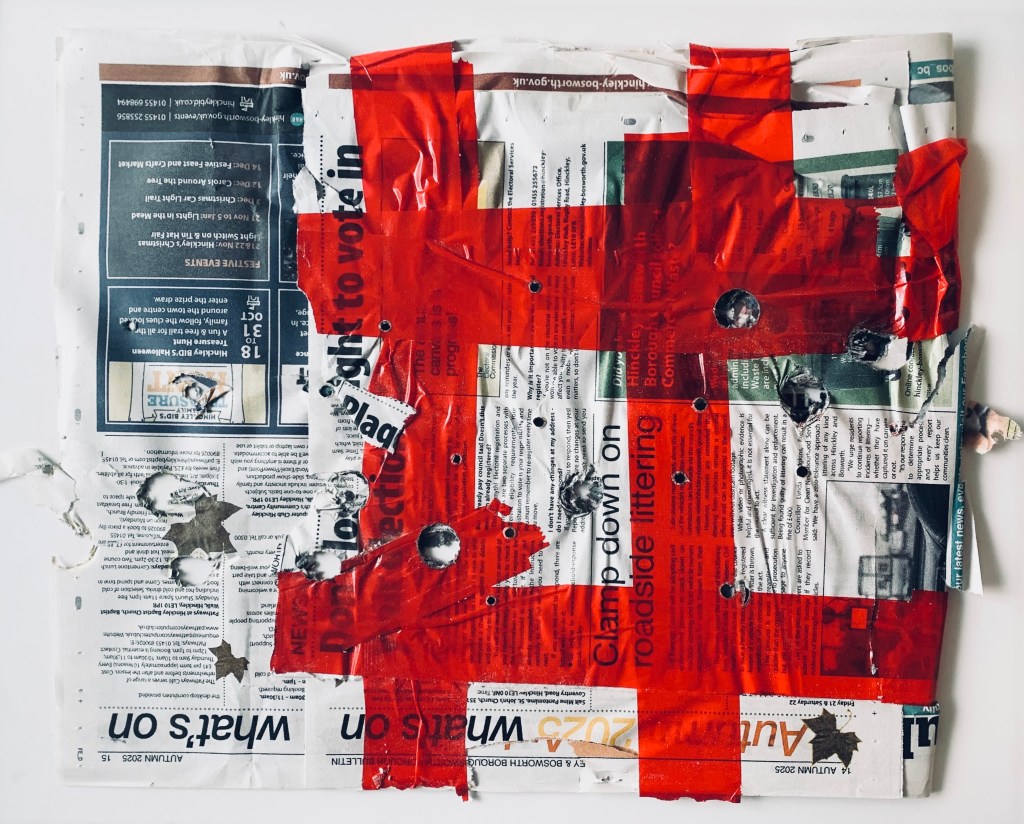

Contemporary art is increasingly understood as a practice deeply embedded in the lived, social, and historical realities of human environments. In this framework, art is not something that can exist anywhere, abstracted from context; rather, it emerges from the processes, rhythms, and relations that constitute a place. The notion of the ‘artist of place’ — developed in opposition to the gallery-based artist and the instrumental ‘artist of site’ — repositions art within social, civic, and historical frameworks, emphasising collaboration, ethical engagement, and responsiveness to local conditions. These artists demonstrate that art practice is inseparable from the everyday acts, values, and structures that shape our cities, institutions, and communities. In this sense, art is communal, systemic, and embedded within the ongoing life of a place.

Reclaiming Art in Context and Community

The term ‘artist of place’ foregrounds the relational and ethical dimensions of contemporary artistic practice. Unlike an ‘artist of site’, who treats the location instrumentally — as a blank container for aesthetic projection — the ‘artist of place’ operates by listening, observing, and responding to the accumulated meanings, social relations, and cultural histories embedded in a location (Kelley, 1993). While the site-oriented artist imposes a pre-conceived artistic language any place and producing work that could exist anywhere, the ‘artist of place’ allows the location itself to generate the content and context of the artwork. In this sense, place-responsive art does not overwrite history; it reveals, amplifies, and enacts the hidden or overlooked narratives that have accumulated over time.

According to Jeff Kelley, the practices of the ‘artist of place’ resemble those of anthropology, archaeology, sociology, and even therapy. They excavate historical layers, map social structures, reveal unconscious narratives, and attend to the rhythms and memories of everyday life. Such practices confront exclusionary power dynamics, question whose voices are represented, and challenge assumptions about public space. The work produced may take the form of walking tours, oral histories, collaborative installations, or architectural interventions. In each case, the goal is not aesthetic ornamentation or decoration but the reinvigorating of public life — making visible the interwoven layers of experience, memory, and social activity that constitute a place.

Working as an ‘artist of place’ is not simply an aesthetic choice — it is an ethical poisoning of practice. The artist respects what already exists, listening before acting, resisting the urge to flatten histories, and acknowledging the multiplicity of experiences within a location. This is an ethic of hospitality which contrasts sharply with traditional gallery-based practice and creates a space for shared reflection, dialogue, and wider engagement. Place-responsive art, therefore, accepts uncertainty, opacity, and multiplicity, and often produces work that challenges assumptions and encourages new ways of seeing.

From Artist of Place to Mass Artist

While the ‘artist of place’ highlights responsiveness and interpretation, the concept of the ‘Mass Artist’ extends these ideas into a distributed framework. The ‘Mass Artist’ recognises that the creative capacities associated with art — imagination, synthesis, care, and composition — are already present across the social body. In this model, the artist is not the originator of meaning but one agent among many within the collaborative production of place. Artistic agency becomes decentralised, embedded in everyday practices such as organising festivals, repairing buildings, coordinating transport, or cultivating communal spaces. These activities, though not traditionally considered ‘artistic,’ constitute materially aesthetic interventions in the structuring of the shared life.

The ‘Mass Artist’ reframes the question from “how does the artist respond to place?” to “how is artistic capacity already present within the distributed systems of place?” In this sense, places are not empty canvases awaiting interpretation but ongoing collaborative projects, produced by planners, engineers, cleaners, residents, administrators, migrants, and activists. The artist’s role becomes catalytic, amplifying existing capacities, mediating between actors, and aligning creative intelligence across the social body. Art, under this model, is inseparable from the ordinary labours, improvisations, negotiations, and choreographies that constitute public life.

Historical Antecedents: Coventry and the Integration of Making

The 1940 declaration at the ‘Coventry of Tomorrow, Towards a Beautiful City’ exhibition anticipated this collapse of disciplinary separation:

ART IS INTEGRATING

ARCHITECTURE PAINTING / SCULPTURE AND LIVING

THE WELL MAKING OF / THAT WHICH NEEDS MAKING

EATING DRESSING HOUSING / ENGINEERING

This manifesto insisted that art should not exist in isolation but as a synthesis with building, feeding, clothing, and organising. In the context of post-War reconstruction, it proposed that culture must take material form in the shaping of cities and social systems. When read through the lens of the ‘Mass Artist’, the statement extends further: life itself is already a composite aesthetic project, and the role of the artist is to recognise, participate in, and enhance the distributed aesthetic capacities of collective labour.

Coventry’s vision, linking art to everyday life and civic labour, foreshadows contemporary practice in which the artist’s intervention is inseparable from community, infrastructure, and governance. The ethical implications of this approach resonate with the principles of place-responsive art, emphasising collaboration, historical consciousness, and attention to lived experience.

Specificity, Distribution, and Relational Intelligence

Place-responsive art values specificity, but the ‘Mass Artist’ situates this specificity within broader systems of production and social networks. Places are unique, but they are also embedded in shared infrastructures — supply chains, planning regimes, digital networks, and legal frameworks. Art does not simply surface these connections but makes relational systems intelligible. The artist’s task shifts from authorship to participation, recognising that meaning is co-produced and that creative capacity is distributed across the social body.

In this sense, the future of place-responsive practice is participation in shared labour, not the imposition of aesthetic objects. Artistic capacity is already embedded in governance, community organising, and collective care. Recognising this distributed intelligence allows the artist to intervene ethically and effectively, amplifying existing capacities rather than claiming exclusive authorship.

Conclusion

The ‘artist of place’ represents a critical shift in contemporary art: away from autonomous objects and towards embedded, ethical practice attentive to social, historical, and lived realities. By listening, excavating, and revealing, the ‘artist of place’ foregrounds the meanings inherent in locations and communities. The ‘Mass Artist’ extends this perspective, situating artistic capacity within the distributed systems that constitute collective life. Here, art is inseparable from governance, infrastructure, community, and everyday labour.

From Coventry’s wartime manifesto to more contemporary initiatives, the ethical, aesthetic, and civic implications are clear: art is not placed into context; context is already aesthetic, already political, already constructed. The role of the artist is to recognise, participate in, and amplify this collective creative intelligence. In this synthesis, art ceases to be a discrete object and becomes a condition of common life itself — a practice of listening, participation, and distributed making.

[1.245 words]

— — —

…and I said: “I paint so I’ll have something to look at.” And sometimes I said: “I write so I will have something to read.” One thing that I am involved in about painting is that the painting should give man a sense of place: that he knows he’s there, so he’s aware of himself. In that sense he relates to me when I made the painting because in that sense I was there.

– Barnett Newman: ‘Interview with David Sylvester (1965), in ‘Selected Writings and Interviews’, University of California Press, 1992, p257

. . .practice [as] glittering liveliness / drawing on Bataille’s philosophy / art = framed as sacrifice and sovereign moment = a rupture from profane, utilitarian time into the sacred instant, beyond discourse, knowledge, or ego.

David Patten: ‘Aesthetic Thresholds: Barnett Newman’s Zip and Jaspers’ Limit-Situation’, 2025. How Barnett Newman’s iconic ‘zips’ function as aesthetic parallels to philosopher Karl Jaspers’ concept of the ‘limit-situation’, both interrupting normal experience to push individuals toward profound, transformative awareness and the existential ‘Encompassing’ (das Umgreifende) beyond rational understanding, a connection supported by Newman’s ownership of Jaspers’ writings.

— — —

Working Notes | Carl Einstein

between painting and architecture = “plastic moment” [ = “plastique” (sculpture) = a way of innervating space, and organizing it around a plurality of “central points” and “accents of composition” which could not only find a place within a void of matter, a hollow, but even introduced a third dimension outside sculpture, within the two dimensions of a picture. The work formally developed its “autonomy” within an inner structure which freed it from any dependence with regard to the viewer’s eye. [file: Einstien | Critique d’art]

The tearing, both physical and ontological, between architecture and painting, between plastics and the plane, between statics and movement testified to a strong tectonic will, but which did not find a synthetic art and, a fortiori, the ontological foundation to support it.

Die Aktion / 1912 / open to different anarchist and anti-materialist currents / notions of revolt / to overthrow the existing order, maintained by social democracy in its complicity with parliamentary democracy / ontology did not reside primarily in aesthetics, politics or economics, but was constituted between all these domains at the same time / revolt = “primitive” in its form / primitiveness = a direct attitude, independent of any mediation

the subjective revolt / [Benjamin] “Let things continue as before: that is the catastrophe” / [Einstein] “… the aesthetic illusionism of democracy consisted of the concealment of its permanent catastrophe under the beautiful proportions of consensus.”

sensitive catastrophe / “give form to history” [Geschichtebildend]

Art reproduced objects, history, facts, liberal democracy, power relations / this repetition of the same — this “nightmare of history” — maintained by the device of illusion which, enveloping it, shielded it from view: the beautiful, the classic, progress, democracy and all that at the same time.

the “primitive” = end of aesthetic mimesis / a primitive exposure = “the univocal man, who must act, whether in books, in paintings, anywhere. We have had enough of dialecticians, comedians and ascetic artists (these white lambs) — we demand books, which reinforce and organize actions; paintings, without the inhibitions of corrupting costumes, which reinforce the story.”

1912 / the leap / “nothing” or “very little” = “primitive” as “an impoverishment” / “It is better to remain with nothing and stick to decent poverty than to continue with the superfluous.”

univocal and uncompromising, the primitive was a universal ontological category, which found its actualisations in all fields of life / we lack…univocal, uncompromising forces / antihumanism and antirationalism / respect of absolute values / an antihumanist lacking religious absoluteness, but whose intellectual efforts were constantly directed towards the transformation of reified history into human history

a divine surplus / to protect oneself at all costs from the danger of optimistic and blissful humanism / the rupture of time / the “univocity” and “intransigence” of the primitive = an apocalyptic temporal action = a continuous time suddenly cut off and stopped / a progressive revelation of the divine spirit

“…to no longer remain isolated and to no longer submit to a narrow, although decisive, present.” / the historical present imprisoned subjectivity

conception of time / univocity [“with one voice”] / Jetzt [Now] / plurivocity of styles and forms…activating all layers of time = a synchrony, a Now / understood not as particular arts, but as principles and processes

[Sebastian Zeidler ‘Braque’s Passion’] “…explains that for Einstein the ‘basic contrast’ [Grundkontrast], i.e. the surface-to-surface connection of space in the Cubist tableau object = political meaning…beyond the immanent perspectives of painting = the picture surface in Cubism is understood as the antagonist of the artist’s subject, as a resistant power that opposes the sovereign gesture of interpretation, the relationship between the subject and its world is redefined.”

Einstein ‘Cubism’ chapter 3 (‘Cubism’s Passion’) …’basic contrast’ [Grundkontrast] = the tension between space and canvas, representation and medium = study of the ‘picture objects’ and ‘picture bodies’ in Picasso and Braque around 1911/12 / Zeidler / Braque = sequence and directionality of experience to explode into an “unpredictable openness” (p123) = Braque’s painting of new beginnings = counterpart to the revolutionary theory of Rosa Luxemburg (at whose grave Einstein gave a speech)…

“Zeidler” + “Grundkontrast” / gründliche Umbildung in the art: a ground transformation that joined surface and space into a new kind of intimacy + gründliche Spannung at work: a ground tension = a negativity of groundlessness = an original event = a visual revolution

the opposition between volume-seeing [will to subjectivation] + the surface [objective counterpart] = [Einstein] foundational contrast (Grundkontrast) = ethical value / Getting rid of a fiction enables you to act, and Cubism’s act was one of liberation: the liberation of the artist from his fictive mastery over the world to his acceptance of his actual precariousness within it—and to an invention that was enabled by that acceptance.

…and the place of artists will have been reclaimed.

A place comes into art loaded with content. An artist comes to a place in one of two ways: either loaded with content or, like a clean slate, ready to receive, interpret and represent what is already there. If the former, an artist will displace the resident meanings of a place with his preconceptions about art. If the latter, she will make those meanings visible as if for the first time. In so doing she may also make something that bears little resemblance to art; it may look like beach furniture, feel like a walking tour, read like an ethnic community library, sound like oral history, pass by like a parade or be organised like a photography competition. Having being made by an artist, however, it will be none of those things alone.

To borrow a phrase once again from Allan Kaprow “It will be art without necessarily being “art-like”. It will be art “like” something else: like architecture, like street life, urban design, like social research, like outdoor advertising, like memorials, like graffiti, like archival photography, like turn-of-the-century graveyards for the stillborn infants of unwed mothers. What this means is that a place will be both the content and the context of an art of place: it will have a kind of double life. In place artists engage meanings that may have nothing to do with art, but which are framed, proposed or clarified in the engagement. Like archaeologists, contemporary artists of place excavate the accumulated history and character of a place; like anthropologists, they study the institutions, myths and customs that characterise a place; like psychotherapists, they unlock the unconscious assumptions and forgotten secrets that keep a place’s histories and intentions hidden from public view; like witches or magicians, they invoke the rhythms and spirits of a place; like sociologists, they measure the social systems that give a place its power; and like social activists, artists of place confront the rhetorics of exclusion and power that keep certain places off limits to dissenting voices, which means that the thresholds now before us are fundamentally political: metaphors for access and belonging, for empowerment and remembering.

– Jeff Kelley: Keynote Address, ‘Public Art — The New Agenda’ (conference), The University of Westminster, 18 November 1993

Working Notes:

[Ehrenzweig, Anton (1967). The Hidden Order of Art. University of California Press]

Anton Ehrenzweig’s depth mind + Jeff Kelley’s artist of place = a practice in which meaning is not imposed by an already-formed intelligence but allowed to surface through sustained, non-dominating attention to what is already at work.

Ehrenzweig: Surface Mind vs Depth Mind

Surface mind: operates through clarity, control, and discrimination / organises perception according to already-known categories and forms / seeks coherence, legibility, and mastery / privileges composition, intention, recognisable form, and ‘good design’, and overwrites ambiguity in order to stabilise meaning.

Depth mind: operates through indeterminacy, diffusion, and unconscious organisation / tolerates contradiction, excess, and incoherence / allows latent structures to emerge without forcing them into predefined forms / works through process, repetition, material insistence, and non-hierarchical attention, and meaning appears after the fact, as something discovered rather than imposed.

Depth mind is not irrational chaos—it has its own order, but one that surface mind cannot initially recognise.

Kelley: Artist of Site vs Artist of Place

Artist of site: treats site as a neutral or interchangeable container / brings a pre-existing artistic concept or language and installs it onto the site / the work primarily reflects the artist’s discourse, not the site’s internal meanings / the site is instrumentalised—used to validate or frame the artwork— and local histories, social relations, and symbolic textures are displaced and/or overridden.

Artist of place: sees the place as already meaningful, structured, and active / works by attending to the existing narratives, rhythms, and material conditions of the place / does not ‘add meaning’ but renders visible what is already operating / the work emerges from prolonged engagement, listening, and responsiveness, and meaning appears as revelation, not imposition—“as if for the first time” / the approach is ethical as well as aesthetic: it concerns responsibility to what precedes the artist.

[Ehrenzweig] Surface mind + [Kelley] Artist of site = imposes order from above / prioritises clarity and control / assumes the field is inert until acted upon.

[Ehrenzweig] Depth mind + [Kelley] Artist of place = allows meaning to emerge from within / accepts opacity and delay / treats the field as already structured but not yet legible.

Ehrenzweig = tension is intra-psychic / both surface and depth mind coexist within the artist / failure occurs when surface mind dominates too early, suppressing depth processes = problem of premature organisation.

Kelley = tension is relational and spatial / the conflict is between the artist and a pre-existing place / failure occurs when the artist refuses to let the place speak = problem of epistemic violence or colonisation.

Surface mind / artist of site: meaning is projected / the work confirms what the artist already knows / the field is reduced to a backdrop.

Depth mind / artist of place: meaning is disclosed / the work surprises the artist / the field resists mastery and remains partially opaque / meaning requires a suspension of authority.

[Ehrenzweig] ethics of self-emptying / tolerance not-knowing / delayed judgement = risks disorientation.

[Kelley] ethics of hospitality / receiving what is given (already there) / listening before acting / accepting limits on authorship.

Both oppose the fantasy of sovereign artistic control.

Ehrenzweig’s ‘depth mind’ and Kelley’s ‘artist of place’ both describe a practice in which meaning is not imposed by an already-formed intelligence but allowed to surface through sustained, non-dominating attention to what is already at work.

Manduessedum = a small horse, pony + a chariot + a city; an old fortification; a Roman site

19

The paradox of syncretistic vision can be explained in this way. Syncretistic vision may appear empty of precise detail though it is in fact merely undifferentiated. Through its lack of differentiation it can accommodate a wide range of incompatible forms… Nevertheless, syncretistic vision is highly sensitive to the smallest of cues and proves more efficient in identifying individual objects.

20

It impresses us as empty, vague and generalized only because the narrowly focused surface consciousness cannot grasp its wider more comprehensive structure. Its precise concrete content has become inaccessible and ‘unconscious’.

294

Dedifferentiation suspends many kinds of boundaries and distinctions; at an extreme limit it may remove the boundaries of individual existence and so produce a mystic oceanic feeling that is distinctively manic in quality. Mania in the pathological sense endangers the normal rational differentiations on a conscious level and so impairs our sense of reality. By denying the distinction between good and bad, injury and health it may serve as a defence against depressive feelings. But

295

on deeper, usually unconscious, levels of the ego dedifferentiation does not deny, but transforms reality according to the structural principles valid on those deeper levels. [. . .] The artist must not rely on the conventional distinctions between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ if he attempts truly original work. Instead he must rely on lower undifferentiated types of perception which allow him to grasp the total indivisible structure of the work of art. [. . .] The scanning of the total structure enables him to revalue details that initially appeared good or bad. He may have to discard a happy detail achieved too early, which now impedes the flow of his imagination; instead he may take an apparently bad feature as his new starting point. The scanning of the total structure often occurs during a temporary absence of mind. One could say that during this gap in the stream of consciousness the ordinary distinctions between good and bad are ‘manically’ suspended. Oceanic dedifferentiation usually occurs only in deeply unconscious levels and so escapes attention; if made conscious, or rather, if the results of unconscious undifferentiated scanning rise into consciousness, we may experience feelings of manic ecstasy. The swing between manic and depressive states may be a direct outcome of the rhythmical alternation between differentiated and undifferentiated types of perception which all creative work entails.

– Anton Ehrenzweig: ‘The Hidden Order of Art’, 1967

09.01.2026 | WDB 1971

Draft summary: the primacy of practice over abstract theory / to rethink / a practice with its own material conditions and effects / and rejections / painting does not culminate in a purified essence but remains caught in overdetermined tensions between materials, institutions, ideologies, and modes of perception / a site of structural contradiction / material conditions not aesthetic mystification vs institutional approaches to painting = critical re-description of painting’s conditions / refusal of closure = painting permanently “under struggle” / [revolutionary ruptures] / concepts of interconnected practices / theory itself as a kind of practice / integrated yet relatively autonomous and mutually affecting / refusing identification with image, composition, depth, or authorial intention / non-privileging of subject, gesture, or site / de-hierarchisation: multiplicity without separation / the work functions when reactions (aesthetic, institutional, authorial) are suspended / processes are allowed to unfold without grasping / meaning is not affirmed or rejected, but circulated = equanimity as material organisation + distributed operational awareness / materialist practice insists on making conditions visible / post-studio constructed practice = suspension of separative operations (forms, identities, and reactions) -> collective production = anti-expressive discipline -> reconfigured common material conditions / theoretical vigilance = a collective anti-expressive discipline aimed at interrupting and dismantling assumptions / suspending authorial identity, hierarchical form, and habitual attachment -> engaging in conscious, alternative actions, behaviours and practices / non-separation can only exist as a provisional, collective, and contested arrangement towards the disciplined suspension of separative reactions within shared production / operationalised as anti-expressivity, distributed authorship, and procedural transparency = collective anti-expressivity that suspends habitual interpellation rather than cultivating insight or bliss.

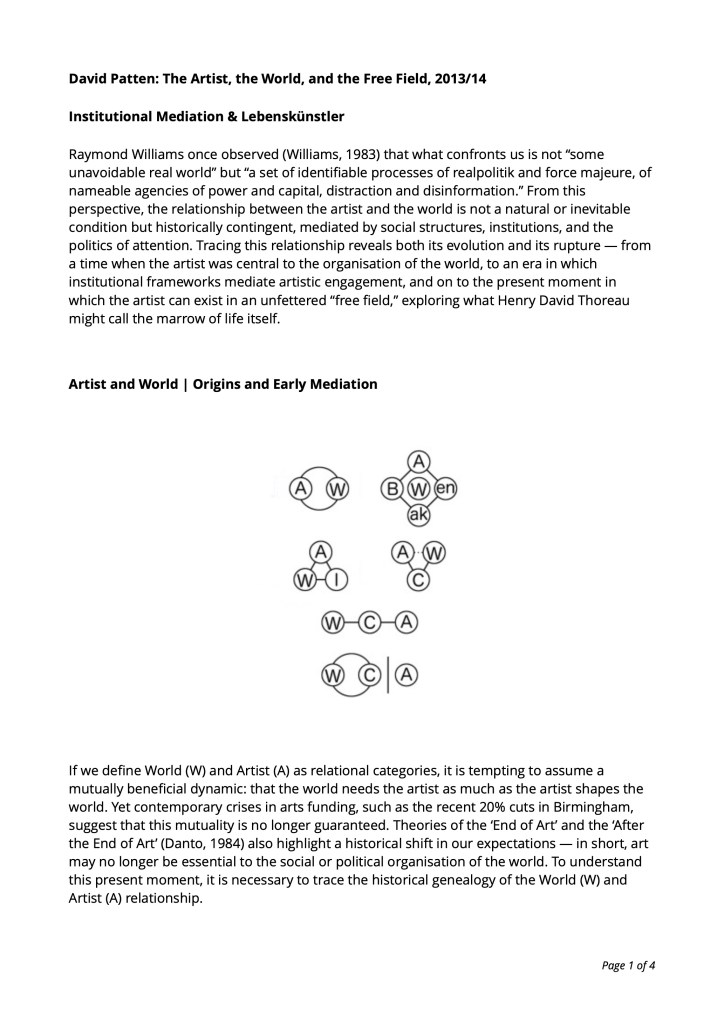

David Patten: The Artist, the World, and the Free Field, 2013/14