David Patten’s ‘The Question Remains: Is There a Secular Self-Emptying?’, SBN, 1 November 2021

Overview

An examination of whether the Buddhist concept of self-emptying (anattā, sunyata) can be meaningfully understood in a secular way, without relying on religious metaphysics. Drawing on art history, philosophy, theology, and personal accounts to frame self-emptying as a lived, experiential process rather than a doctrinal belief.

Key Threads and Thinkers

• Carl Einstein – As an anarchist art historian, Einstein linked political collectivity and Cubism to the dissolution of the egoic ‘I’. His description of Cubist disruption of objecthood questions the stability of bodily and perceptual certainties.

• Emilia Fogelklou – Her “Revelation of Reality” described an all-encompassing, boundless perception, dissolving the individual ‘I’ into a radiant field of relations.

• Petra Carlsson Redell – On Fogelklou’s style: her authorial voice scatters into a patchwork of others’ voices, embodying self-emptying in writing form.

• Winthrop Judkins & Fluctuant Representation – Judkins analysed Synthetic Cubism’s capacity to create “a deliberate oscillation of appearances” and “studied multiplicity of readings.” This visual instability mirrors the destabilisation of a fixed self—requiring the viewer to hold multiple, shifting identities in play.

• Stephen Batchelor – Emptiness is not a concept but a direct experience of the absence of fixed self or reality, like “stumbling into a clearing in the forest.”

• Stephen Rowe – True self emerges through mutual recognition and being “with and for the other” in the shared life of the world.

• Martin Hägglund – Reframes Hegel’s notion of Entäusserung (self-emptying) as secular spiritual commitment: discovering who we are through engaged, risky, embodied action in community, rather than solitary introspection.

Conclusion

Secular self-emptying might not require importing ideas from Christianity or Buddhism, but can be found in ordinary experience (“pens, bananas, and pots”), in the perceptual and conceptual fluidity of Cubist art (particularly Braque), and in the ethical, relational openness described by thinkers like Hägglund. Self-emptying, in this view, is both an aesthetic and ethical practice—embodied in how we see, make, and relate.

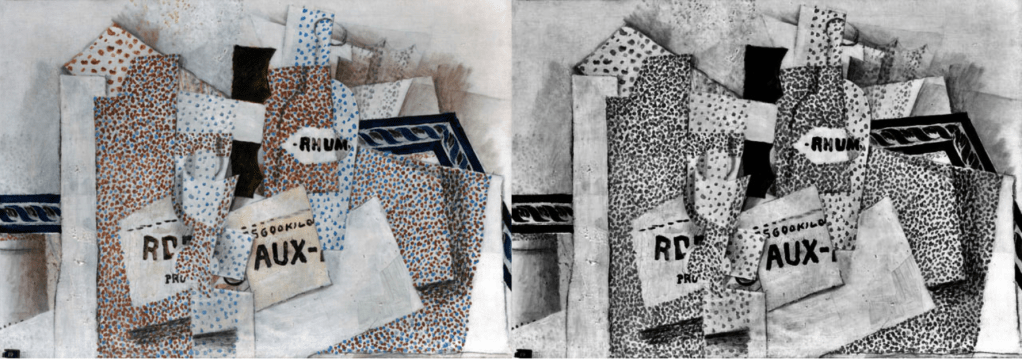

Georges Braque: ‘Bouteille de rhum (Bottle of Rum)’ (Spring) 1914, oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection; The Met (New York)

Pablo Picasso: ‘Fruit Dish, Bottle and Violin’, oil on canvas, 1914, 92 x 73 cm, National Gallery, London

Text:

‘The question remains, is there a secular self–emptying?’

Secular Buddhist Network, 1 November 2021 (revised 2025)

David Patten does not claim to deliver a definitive ‘secular self–emptying’, but rather invites reflection on how one might live a kind of self-emptying in secular life — in everyday acts, creative practice, and relational engagement — without relying on traditional religious frameworks. He leaves open whether a complete equivalence between Buddhist emptiness and Christian kenosis can be sustained, advocating instead for a more fluid, embodied, and context-sensitive understanding.

Drawing on the writings of art historians, political activists, philosophers, Christian theologians, and the secular Buddhist Stephen Batchelor, the author explores how the movement away from the egoic self toward the experience of ‘not–self’ might be understood as a process of secular self–emptying.

Carl Einstein at Durruti’s funeral. On the left of the photo, wearing round glasses.

I

As técnico de guerra in Buenaventura Durruti’s international fighting group of the same name, the art historian Carl Einstein delivered an obituary for the recently fallen anarchist leader on the CNT-FAI’s anarcho-syndicalist radio station in Barcelona in November 1936. [1] In declaring that “in the Durruti Column only the collective syntax was known,” Einstein concluded a critique first articulated in his 1935 Die Fabrikation der Fiktionen (The Fabrication of Fictions): the rejection of bourgeois individualism in favour of a collective form of consciousness and creation. His fervour for the eradication of the primitive word Ich (‘I’) reached its highest pitch in that late November broadcast—a moment in which aesthetic, political, and existential revolt briefly converged.

II

A few years earlier [2], in his writings on Cubism, Carl Einstein observed that “to unhinge the world of objects is to call into question the guarantees of our existence.” For Einstein, the naïve observer “believes that the appearance of the human figure is the most trustworthy experience a human being can have of himself; he dares not doubt this certainty, even as he suspects the presence of inner experiences. He imagines that, in contrast to this abyss of interiority, the immediate experience of his own body constitutes the most reliable biological unit.”

III

At the age of twenty-three, the Swedish writer and theologian Emilia Fogelklou underwent a transformative experience she later described as her “Revelation of Reality” [3]. “It was not observation,” she wrote, “but a rising into total view—an attention that intoxicated not only the eyes that saw but the whole that lived, saw, knew—without form or boundaries.” She came to understand that “the very art of radiance is its ‘form’: vibrations through an infinite multiplicity of personal worlds and circles of figuration, in all degrees of reach and creative transformation.”

IV

In describing Fogelklou’s distinctive writing style, Petra Carlsson Redell, a minister of the Lutheran Church of Sweden, observes [4] that in Form och strålning (Form and Radiance) “the ‘I’ who speaks—the author subject—recurrently disappears. If a phantasmic author–subject exists in her work, it is fragmented on every page.” Fogelklou’s contemplative writing, Carlsson Redell continues, “is a patchwork: her essays are composed by an authorial voice that gathers other voices and, through this very act of gathering, disperses herself.” This self-scattering, she notes, can make Fogelklou’s prose difficult to follow, “yet not because of any failure of clarity or conviction.”

V

Kathleen March-Martul explains [5] that Cubist painters employed an illusionary device termed “fluctuant representation” by W. Judkins. This device produces a multiplicity of readings: the work appears emergent, unfolding, and perpetually shifting in its semiotic identity as perceived by the spectator. Underlying this technique, March-Martul notes, was the Cubists’ desire to demonstrate that the senses inevitably deceive the human eye. In simplified terms, this involves representing a form so that it is first recognised as one object but subsequently perceived as another—or as part of another. Such multiple readings arise from the form’s structural ambiguity, its capacity to perform the syntagmatic and paradigmatic functions of more than one artistic figure. The viewer, therefore, is compelled to discern both the features of the ambiguous form and its relational role within the total composition.

VI

In his 1954 Harvard thesis on Synthetic Cubism [6], Winthrop Judkins concluded that “In the broader sense, it is submitted that within the limits of the typical studio still-life setup, a restriction which, for that matter, was probably necessary to this end, virtually the entire fabric of normal representation was explored and transformed into fluctuant representation.”

VII

Six years earlier, Judkins had concluded [7], “…that which all these things have in common, that of which they are an unending variety of manifestations, is this:

• A Deliberate Oscillation of Appearances

• A Studied Multiplicity of Readings

• A Conscious Compounding of Identities

• An Iridescence of Form.

VIII

In a short chapter on ‘emptiness’ [8], Stephen Batchelor writes “Pens, bananas, and pots are self-evident, instantly recognisable things. But subject them to a little scrutiny, and that certainty begins to waver. Things are not as clear-cut as they seem. They are neither circumscribed nor separated from each other by lines. Lines are drawn in the mind. There are no lines in nature.”

IX

Later, in the same chapter, Batchelor tells us that “To know emptiness is not to understand the concept. It is more like stumbling into a clearing in the forest, where suddenly you can move freely and see clearly. To experience emptiness is to experience the shocking absence of what normally determines the sense of who you are and the kind of reality you inhabit. It may last only a moment before the habits of a lifetime reassert themselves and close in once more. But for that moment, we witness ourselves and the world as open and vulnerable.”

X

The 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions, followed by the publication of Paul Carus’ The Gospel of Buddha the following year, inaugurated a century of Eastern–Western philosophical dialogue. This exchange often sought to establish an equivalence between the Christian notion of kenosis — the self-emptying of God through incarnation — and the Buddhist concept of śūnyatā, the emptying of self in the realisation of non-self.

Stephen C. Rowe [9] concludes that the “…birth of the true self through surrender to the first law of life: other–preservation, mutual realisation, the fullness of our own presence only occurs when we are present with and for the other. …transforming our lives and the larger life we share on this fragile and still-enchanted earth.”

The question remains, is there a secular self-emptying?

XI

The Swedish philosopher, Martin Hägglund, tells us [10] that “Spiritual life does not descend or ‘fall’ into finitude. Rather, spiritual life is from the beginning subject to — and the subject of — a finite form of life. We can see how Hegel makes this point by converting Luther’s religious conception of Entäusserung [‘kenosis’] as divine love into a secular notion of spiritual commitment. The term Entäusserung is used frequently both in Hegel’s ‘Phenomenology of Spirit’ and his ‘Science of Logic’, but it becomes particularly significant in the concluding sections of the ‘Phenomenology’ where Hegel employs it on every page. At stake here are the conditions of possibility for leading a spiritual life, both individually and collectively. Leading a spiritual life requires a conception of who we ought to be as individuals and as a community, what Hegel calls an ‘Idea’ of who we are. Following Hegel’s secular notion of the incarnation, the Idea of who we are is not something that can exist in a separate realm; it must be materially embodied in our practices. Moreover, the Idea of who we are is not contemplative. We cannot discover who we are through introspection, but only by emptying ourselves out in the sense of being wholeheartedly engaged — being at stake, being at risk — in what we do and how we are recognised by others. The Idea of who we are is not an abstract ideal that is external to our form of life; it is the principle of intelligibility in light of which we can succeed or fail to be who we are striving to be.”

In this, Entäusserung is relinquishing / giving up / abandoning / releasing / surrendering and/or alienating.

Perhaps a secular self-emptying is not found when looking for equivalence between Buddhism and Christianity.

Perhaps it is already here, waiting to be discovered (or re-discovered) in our everyday experience of “pens, bananas, and pots”.

Perhaps, like Carl Einstein and Emilia Fogelklou, we too must seek our self-emptying, fluctuating selves — “without form or boundaries” — in Cubist still-life painting, particularly in the work of Braque and Picasso between spring 1912 and the pre-War summer of 1914.

“This painting of the absolute, this grasping after the pure visual function, demonstrated that the absolute is not some ideological generality, but always a perfectly concrete individual experience that has nothing to do with any metaphysical or posthumously retrospective theoretical product.”

– Carl Einstein: ‘Revolution durchbricht Geschichte und Überlieferung’, unpublished, 1921.

References:

1. Franke, Anselm, and Tom Holert. 2018. Neolithic Childhood: Art in a False Present, 1930. Zurich: Diaphanes.

2. Einstein, Carl. 1929. Notes sur le cubisme. Documents 1 (3): 146–55. Translated and introduced by Charles W. Haxthausen as “Notes on Cubism.” October 107 (Winter 2004).

3. Fogelklou, Emilia. 1958. Form och strålning [Form and Radiance]. Stockholm: Bonniers.

4. Carlsson Redell, Petra. 2014. Mysticism as Revolt: Foucault, Deleuze and Theology Beyond Representation. Aurora, CO: The Davies Group.

5. March-Martul, Kathleen. 1981. Cubist Fluctuant Representation in the ‘Creacionista’ Poetry of Gerardo Diego. Romance Notes 22 (2): 171–79. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, Department of Romance Studies.

6. Judkins, Winthrop. 1976. Fluctuant Representation in Synthetic Cubism: Picasso, Braque, Gris, 1910–1920. London: Taylor & Francis.

7. Judkins, Winthrop. 1948. Toward a Reinterpretation of Cubism. The Art Bulletin.

8. Batchelor, Stephen. 1997. Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

9. Rowe, Stephen. 1994. Rediscovering the West: An Inquiry into Nothingness and Relatedness. Albany: SUNY Press.

10. Hägglund, Martin. 2019. This Life: Why Mortality Makes Us Free. London: Profile Books.

©David Patten, 29 October 2021 / revised 13 October 2025

Pablo Picasso: ‘Green Still Life’, oil on canvas, Avignon, summer 1914, 59.7 x 79.4 cm, Lillie L. Bliss Collection, MoMA (New York)

Comment

‘Secular Self Emptying’, SBN 2021 (revised 2025)

Core Thesis

The author explores how the movement away from the egoic self toward an experience of ‘non-self’ or ‘not-self’ (drawing especially on secular Buddhist thought) can be understood as a process of secular self-emptying. He investigates how this compares and contrasts with Christian notions of kenosis (self-emptying) and how art, philosophy, and spirituality contribute to this conceptualisation.

Key Themes & Arguments

1. Interdisciplinary Foundation

The essay draws on art history, political theory, philosophy, Christian theology, and secular Buddhism (especially Stephen Batchelor) to build its argument. The author uses examples from Cubism, revolutionary politics, and contemplative experience to illustrate how self-emptiness might be lived rather than just theorised.

2. Critique of the Egoic Self

The ‘egoic self’ or ‘small self’ is treated as a mental construct, grounded in static identities and boundaries. The author examines how that model becomes destabilised through deeper scrutiny.

Through minimal distinction between subject, object, and the world, the solidity of self begins to waver.

3. Experiential Emptiness

The author emphasises that “to know emptiness is not to understand a concept” but to have an experiential shift — “stumbling into a clearing” in which the usual sense of “who I am” temporarily dissolves.

This state is fleeting, since habitual sense patterns tend to reassert themselves, but the insight has transformative potential.

4. Secular vs. Religious Self-Emptying

The author examines Christian kenosis (self-emptying) and the Buddhist concept of śūnyatā (emptiness / non-self), questioning whether there is a meaningful secular equivalent.

He engages with Hegel’s adaptation of kenosis (Entäusserung) as a secular spiritual concept, suggesting that spiritual life in a secular framework must be embodied and enacted, not abstract or detached.

5. Art as Metaphor & Medium

Cubist and modernist art (e.g. Braque, Picasso) serve as models for self-emptying: forms that fragment, shift, and resist fixed boundaries mirror how identity might dissolve.

The multiple readings, oscillation of appearances, and ‘fluctuant representation’ in art echo the instability of fixed selfhood.

Conclusion & Open Questions

The author does not claim to deliver a definitive ‘secular self-emptying’, but rather invites reflection on how one might live a kind of self-emptying in secular life — in everyday acts, creative practice, and relational engagement — without relying on traditional religious frameworks. He leaves open whether a complete equivalence between Buddhist emptiness and Christian kenosis can be sustained, advocating instead for a more fluid, embodied, and context-sensitive understanding.