28.09.2024

Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross (Lema Sabachthani), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Jesus? Newman explained

lema sabachthani

Newman said

22.07.2025

01.10.2024

…the problem of boundaries in the Stations / …a peculiar kind of blindness we have about edges – or rather, a blindness about boundary lines. / …there’s a denial of the power of the eye to see, a predication of blindness. For the black and white symmetry — in spite of its material neatness — produces something like the visible-yet-invisible orange line, a bright whiteness that blinds and a black darkness that is visionless. / …the marked line is by following Newman’s gesture of making with the eye, retracing that not-quite-invisible boundary line. / …imperfect boundaries bring into view decisions and impulses about how and where to see and to pause for a moment or move on…seeing is and is not believing. / We are presented with our own blindnesses in stark black and white, and the opportunity for making sense of how our sight is denied as we try to see where we’re headed…

As Newman put it himself, “The cry [Lema Sabachthani], the unanswerable cry, is world without end. But a painting has to hold it, world without end, in its limits.” [ARTnews 65, no. 3 (May 1966)]

– Lisa Claypool: Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross (Lema Sabachthani), June 28, 2017

Title: Aesthetic Thresholds: Barnett Newman’s Zip and Jaspers’ Limit-Situation

© David Patten | ChatGPT formatted 04.07.2025

Abstract: This paper explores the philosophical alignment between Barnett Newman’s abstract expressionist aesthetics and Karl Jaspers’ existential concept of ‘Grenzsituation’ (the ‘limit-situation’). Drawing on Newman’s own writings and the evidence of his ownership of Jaspers’ ‘Reason and Existenz’, the essay argues that Newman’s notion of the ‘zip’ functions as an aesthetic analog to Jaspers’ philosophical construct. Both figures seek to provoke a transformative encounter with the limits of understanding, leading the individual toward a confrontation with existential presence and transcendence.

Introduction

In his 1948 essay ‘The Sublime is Now’, Barnett Newman declared: “Instead of making cathedrals out of Christ, man, or ‘life,’ we are making [them] out of ourselves, out of our own feelings” (Newman, 1990, p. 170). This statement reveals Newman’s modernist ambition: to create artworks that serve as sites of existential intensity and spiritual confrontation. His vertical bands of colour, known as ‘zips’, punctuate vast fields of monochrome, functioning not merely as visual elements but as aesthetic thresholds. While Newman did not explicitly quote Karl Jaspers in his writings, the Barnett Newman Foundation confirms that he owned a copy of ‘Reason and Existenz: Five Lectures’ (Jaspers, 1955/1959). This essay argues that Newman’s concept of the zip operates analogously to Jaspers’ notion of the limit-situation—a confrontation with the limits of understanding that opens the possibility for existential self-realization and transcendence.

Newman’s Sublime and the Function of the Zip

Newman’s commitment to the sublime was not rooted in romanticism or traditional aesthetics of beauty, but in an effort to provoke direct, immediate encounters with the unknown. The zip, first appearing in his 1948 painting ‘Onement I’, divides the canvas without representing anything external. It is a formal disruption that insists on presence, both of the painting and of the viewer. Thomas B. Hess, one of Newman’s closest interpreters, described the zip as a ‘drawing in the viewer’, a marker that makes the flat canvas a field of action (Hess, 1971, p. 53).

Newman rejected narrative and symbolic interpretation in favour of what he called ‘the self-evident’ (Newman, 1990, p. 259). His intention was not to illustrate but to enact. The zip, as rupture and articulation, introduces a confrontation—it is the canvas’s edge, its limit, made visible. It demands that the viewer engage not with an image, but with their own act of perception, making the painting a place of existential encounter.

Jaspers’ Limit-Situation and the Encounter with Being

In ‘Reason and Existenz’, Karl Jaspers articulates the idea of Grenzsituationen or ‘limit-situations’: unavoidable existential conditions such as death, suffering, guilt, and struggle that cannot be rationally resolved (Jaspers, 1955, p. 20). These moments disrupt the continuity of everyday life and force the individual into an encounter with what Jaspers calls ‘Existenz’ or authentic selfhood. The limit-situation is not a problem to be solved, but a threshold to be crossed.

Jaspers distinguishes between objective knowledge and existential awareness. It is in moments of crisis—when the world resists explanation—that the individual becomes aware of their freedom and their potential for transcendence. The limit-situation thus initiates a movement toward what he calls ‘the Encompassing’ (das Umgreifende), the unobjectifiable horizon of all being (Jaspers, 1955, pp. 66–67).

Philosophical Parallels and Aesthetic Convergence

Newman’s zip and Jaspers’ limit-situation both mark a break in the continuity of experience. The zip interrupts the visual field, not with a symbol, but with a presence that resists interpretation. Similarly, the limit-situation interrupts the conceptual field, forcing the individual to confront a reality beyond rational comprehension. Both constructs compel a shift from knowledge to awareness, from perception to confrontation.

Furthermore, both thinkers emphasize the revelatory potential of these ruptures. Newman’s paintings invite a solitary, meditative stance; they do not explain but evoke. Jaspers, too, insists that limit-situations reveal our deepest self not through explanation but through lived experience. As such, the zip can be understood as an aesthetic limit-situation that enacts, rather than illustrates, the existential crisis Jaspers describes.

Newman and Jaspers: A Confirmed Encounter

The Barnett Newman Foundation’s library records confirm that Newman owned ‘Reason and Existenz’ (Jaspers, 1955/1959). While there is no record of Newman quoting Jaspers directly, the presence of this text among his personal materials suggests that he encountered Jaspers’ core existential ideas. The convergence of their concepts—zip and limit-situation, sublime and transcendence, presence and the Encompassing—is too structurally resonant to be dismissed as coincidence.

Conclusion

Barnett Newman’s artistic project, grounded in the visual and the visceral, intersects meaningfully with Karl Jaspers’ existential philosophy. The zip in Newman’s work operates not merely as a compositional device but as a threshold that invites existential confrontation. In this, it echoes the function of Jaspers’ limit-situation: a break that both limits and reveals. Through this aesthetic-philosophical alignment, we can better understand Newman not just as a formal innovator, but as a painter of existential thresholds.

References

Hess, T. B. (1971). Barnett Newman. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Jaspers, K. (1955). Reason and Existenz: Five Lectures (W. Earle, Trans.). Boston: Beacon Press. (Original lectures delivered in 1941). Reprint, New York: The Noonday Press, 1959.

Newman, B. (1990). Selected Writings and Interviews (J. O’Neill, Ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

The Barnett Newman Foundation. (n.d.). Library Archive. Retrieved from http://www.barnettnewman.org/archives/library

© David Patten | ChatGPT formatted 04.07.2025

Footnote 05.07.2025

Kant’s notion that appearance and the thing-in-itself are not two parts of one reality but rather that the thing-in-itself marks the limitation of reason introduces a crucial concept of human finitude. The thing-in-itself is not an inaccessible object behind appearances, but an index of the boundary of cognition—that which cannot be brought into representation yet structures the field of representation itself. It “points to that within appearance that also points to an outside,” suggesting that human beings do not simply perceive what is present but are constantly oriented toward what escapes presence.

This orientation toward the beyond—the inaccessible other side—is taken up by Karl Jaspers, who describes human existence as fundamentally structured by limit-situations (Grenzsituationen). Jaspers emphasizes that the limit (Grenze) should not be mistaken for a border between two domains (such as immanence and transcendence), but should be understood as the condition of finitude itself: “The word limit implies that there is something else, but it indicates at the same time that this other thing is not for an existing consciousness” (Jaspers 1970, II:179). This “other side” is not known, but it is felt, implied, and alluded to in experience—what phenomenology, especially Husserl, calls appresentation.

In phenomenology, appresentation names the way consciousness includes not just what is directly presented, but also what is co-present—implied, anticipated, or retained. When we perceive something, we do so against a background of absent meanings that are nevertheless operative. We never grasp the totality of what is before us, yet we intuit it as total—as something whose fullness is given in part. Thus, human experience is never simply about what is present; it is structured by a dynamic of absence and implication, and therefore by finitude.

It is precisely this logic that Barnett Newman articulates in his reflections on painting. In ‘Onement I’, the first painting where he used the now-iconic zip, Newman describes his realization that the surface was no longer empty or atmospheric—it was full. The zip, rather than dividing the canvas, “creates a totality.” It does not lead the viewer into a representational world or narrative space. Instead, everything is present at once: “the beginning and the end are there at once.” Newman’s aesthetic project can thus be seen as an effort to overcome the pictorial atmosphere—the illusionism and spatial narrative of traditional painting—by asserting a presence that also gestures toward what cannot be fully seen. The zip is not simply a formal device but a phenomenological event: a limit that gathers the painting into a unity, while also marking the point at which vision encounters its own boundary.

Newman’s work resonates with what Jonna Bornemark, following Jaspers, calls the limit-situation—a condition where transcendence is not experienced directly but as an absence that structures immanence. The limit is not a separation but a threshold, a moment where something beyond human comprehension is intimated without being revealed. Similarly, Newman’s painting is not a window into another world; it is an event of totality that includes its own limit—its own pointing-beyond.

This can all be understood through the lens of periechontologie, a philosophizing that orients itself not toward fixed truths or objective knowledge, but toward the encompassing (das Umgreifende). It is a mode of thought that remains with the limit, not to overcome it, but to dwell with the incompleteness that makes all appearance meaningful. It is this structure—the tension between presence and absence, appearance and implication, form and excess—that grounds both human finitude and aesthetic fullness.

Barnett Newman: ‘Selected Writings and Interviews’, University of California Press, 1992 / ‘Statements’, pp189-190.

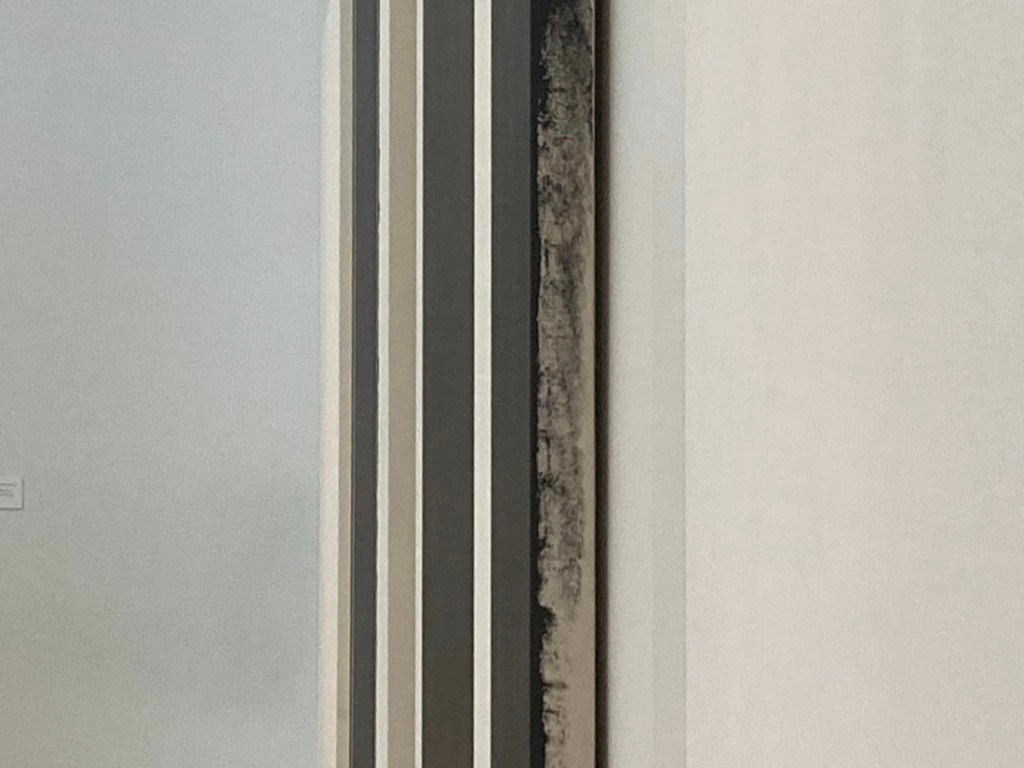

The Fourteen Stations of the Cross, 1958-1966

In this statement, which he wrote for ARTnews for publication* during the course of his exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, Newman elaborates on the spiritual and material challenges he set himself in pursuing the Stations series. He unknowingly began the sequence in February 1958, only a few weeks after he was released from the hospital following a heart attack. With the scant, severe means he allowed himself, Newman eventually achieved a somber intensity that reminded him of the tradition of the Stations: “When I did the fourth one, I used a white line that was even whiter than the canvas, really intense, and that gave me the idea for the cry. It occurred to me that this abstract cry was the whole thing—the entire Passion of Christ.”**

No one asked me to do these Stations of the Cross. They were not commissioned by any church. They are not in the conventional sense “church” art. But they do concern themselves with the Passion as I feel and understand it; and what is even more significant for me, they can exist without a church.

I began these paintings eight years ago the way I begin all my paintings—by painting. It was while painting them that it came to me (I was on the fourth one) that I had something particular here. It was at that moment that the intensity that I felt the paintings had made me think of them as the Stations of the Cross.

It is as I work that the work itself begins to have an effect on me. Just as I affect the canvas, so does the canvas affect me.

From the very beginning I felt that I would do a series. However, I had no intention of doing a theme with variations. Nor did I have any desire to develop a technical device over and over. From the very ginning I felt I had an important subject, and it was while working that it made itself clear to me that these works involved my understand. ing of the Passion. Just as the Passion is not a series of anecdotes but embodies a single event, so these fourteen paintings, even though each one is whole and separate in its immediacy, all together form a complete Statement of a single subject. That is why I could not do them all at once, automatically, one after another. It took eight years. I used to do my other work and come back to these. When there was a spontaneous, inevitable urge to do them is when I did them.

The cry of Lema—for what purpose?—this is the Passion and this is what I have tried to evoke in these paintings.

Why fourteen? Why not one painting? The Passion is not a protest but a declaration. I had to explore its emotional complexity. That is, each painting is total and complete by itself, yet only the fourteen together make clear the wholeness of the single event.

As for the plastic challenge, could I maintain this cry in all its intensity and in every manner of its starkness? I felt compelled—my answer had to be—to use only raw canvas and to discard all color palettes. These paintings would depend only on the color that I could create myself. There would be no beguiling aesthetics to scrutinize, Each painting had to be seen—the visual impact had to be total, immediate—at once.

Raw canvas is not a recent invention. Pollock used it. Miró used it. Manet used it. I found that I needed to use it here not as a color among colors, not as if it were paper against which I would make a graphic image, or as colored cloth—batik—but that I had to make the material itself into true color—as white light—yellow light—black light. That was my “problem.”

The white flash is the same raw canvas as the rest of the canvas. The yellow light is the same raw canvas as the other canvases.

And there was, of course, the “problem” of scale. I wished no monuments, no cathedrals. I wanted human scale for the human cry. Human size for the human scale.

Neither did I have a preconceived idea that I would execute and then give a title to. I wanted to hold the emotion, not waste it in picturesque ecstasies. The cry, the unanswerable cry, is world without end. But a painting has to hold it, world without end, in its limits.

* ARTnews 65, no. 3 (May 1966), pp. 26-28, 57.

** Newsweek, May 9, 1966, p. 100.

02.07.2025

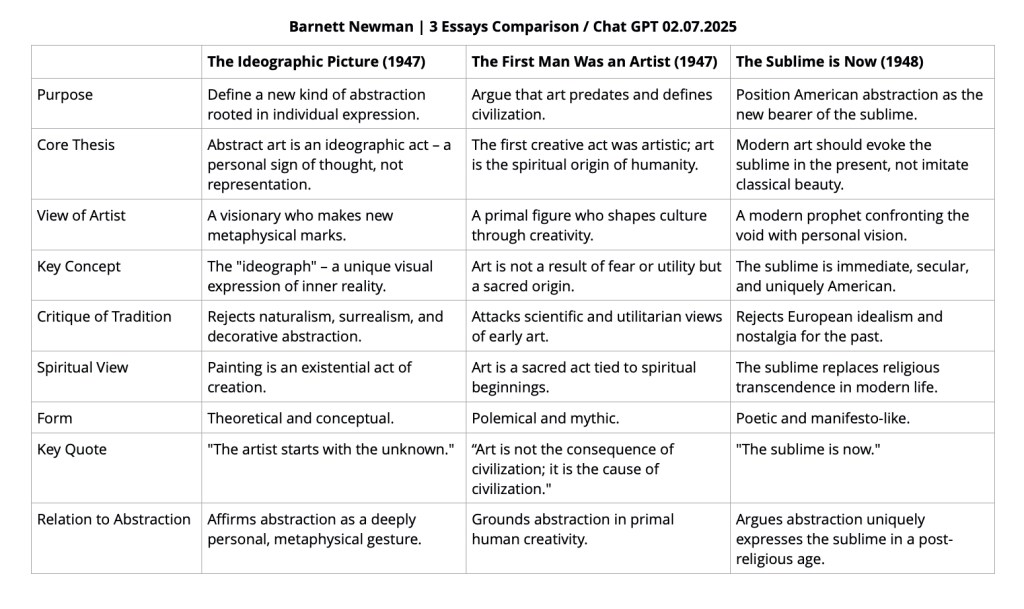

Synthesis of Barnett Newman’s Aesthetic Philosophy (1947–1948)

‘The Ideographic Picture’ (1947), ‘The First Man Was an Artist’ (1947), and ‘The Sublime is Now (1948):

Across these three seminal essays, Barnett Newman articulates a radical vision of art as a primordial, existential, and spiritual act—a departure from aesthetics, tradition, and representation toward the pure, immediate expression of being.

1. Art as the Origin of Human Culture

In ‘The First Man Was an Artist’, Newman insists that art precedes utility—the first creative act of humanity was not making tools, but making meaning. Early humans were spiritual beings, confronting existence, death, and nature through symbolic, expressive acts. This challenges scientific materialism, positioning the artist as the original metaphysical thinker.

2. Abstract Form as Spiritual Vehicle

In ‘The Ideographic Picture’, Newman extends this idea, arguing that the artist’s use of abstract shape is not decorative or formal, but a living vehicle for existential and metaphysical content. A shape is not a stylised symbol or a purified form—it is a carrier of “awesome feelings” and the terror of the unknown. For Newman, the “pure idea” is an aesthetic act, and art becomes a confrontation with life’s deepest mysteries: death, tragedy, nature, chaos.

3. The Sublime as a Contemporary, Existential Force

In ‘The Sublime is Now’, Newman calls for a break from classical traditions of beauty and narrative. The modern sublime is not found in myth, landscape, or history—it is found in the act of painting itself, an existential, revelatory process. This sublime is intimate, spiritual, and immediate—born in the ‘now’ of both the artist’s act and the viewer’s experience.

Newman’s sublime is:

• not illustrated but created through painting

• not a representation of reality, but a new presence in the world.

• not aesthetic in the traditional sense, but metaphysical, immersive, and generative.

4. The Artist as Creator, Not Imitator

Across all three essays, Newman elevates the artist to a mythic status—not a decorator or craftsman, but a visionary, a creator of new worlds. Art is no longer about rendering beauty or conveying stories—it is an ontological event, an embodiment of meaning and presence. The artist is akin to the first human, the shaman, or the prophet—one who confronts chaos and returns with form.

Newman’s philosophy redefines modern art as a spiritual act of creation, where both artist and viewer participate in the forging of meaning from the void. His thought forms a cornerstone of Abstract Expressionism—not just in style, but in intent and metaphysical urgency.