“We are arriving, I am convinced, at a conception of art as vast as the greatest epochs of the past: there is the same tendency toward large scale, the same effort shared among a collectivity. If one can doubt the whole idea of creation taking place in isolation, then the clinching proof is when collective activity leads to very distinct means of personal expression”: thus Léger in Montjoie! in 1913.

– T. J. Clark: ‘Cubism and Collectivity’, in ‘Farewell to an Idea, Episodes from a History of Modernism’, Yale University Press, 1999, p222

— — —

‘Mass Artist‘

[20.07.2023 / draft v4, 03.03.2026]

Abstract

Beginning with Fernand Léger’s 1951 painting The Hands, Homage to Mayakovsky and moving through Antony Gormley’s 1998 Angel of the North, this essay traces the persistent tension between collective labour and individual authorship. While monuments are physically built by many, cultural credit continues to attach to the signature artist. From this contradiction emerges the figure of the ‘mass artist’: a distributed condition of practice shaped by immaterial labour, collective intelligence and technological mediation. Drawing on Negri, Althusser and contemporary debates on AI, the text argues that art is now shaped by networks of shared production — and that painting and sculpture have always been sites where labour, authorship and social relations are made visible. The ‘mass artist’ is not a new phenomenon. It is a recognition of what creativity has always been.

Preamble | ‘The Hands’

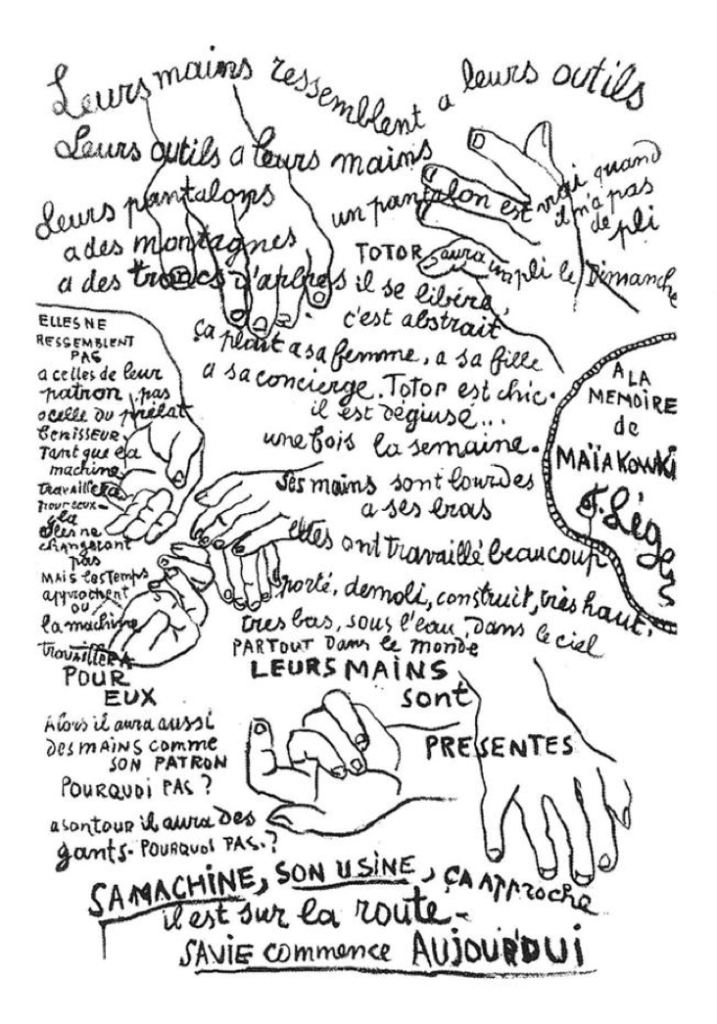

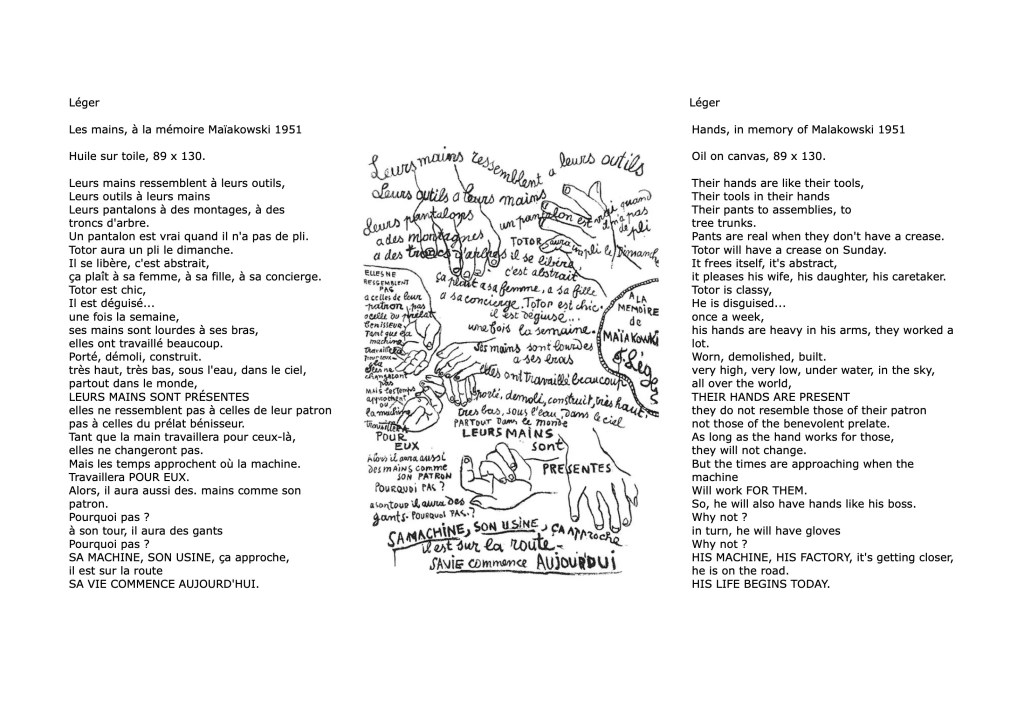

Their hands resemble their tools,

Their tools in their hands

Their pants to assemblies, to

tree trunks.

Pants are real when they don’t have a crease.

Totor will have a crease on Sunday.

He frees himself, it’s abstract,

it pleases his wife, his daughter, his concierge.

Totor is chic,

He is disguised…

once a week,

his hands are heavy on his arms, they have worked a lot.

Worn, demolished, built.

very high, very low, underwater, in the sky,

all over the world,

THEIR HANDS ARE PRESENT.

they do not resemble those of their boss

not those of the benevolent prelate.

As long as the hand works for them,

they will not change.

But the times are approaching when the

machine

Will work FOR THEM.

So, he too will have hands like his boss.

Why not?

In turn, he will have gloves

Why not?

HIS MACHINE, HIS FACTORY, it’s getting closer,

he is on the road.

HIS LIFE BEGINS TODAY.

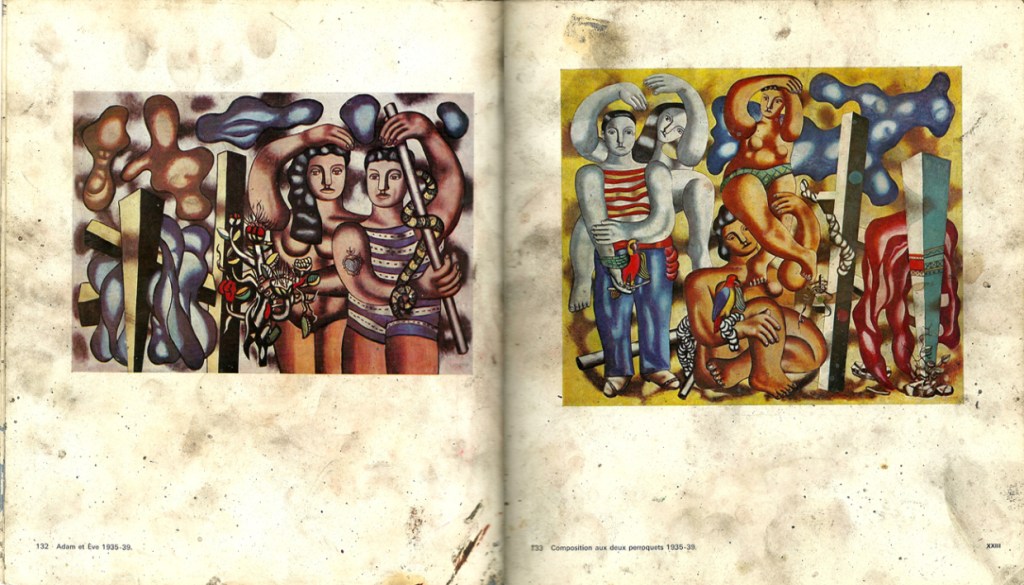

Fernand Léger’s 1951 painting The Hands, Homage to Mayakovsky [oil on canvas, private collection] is a work that refuses to separate thinking from making. Text and image press against each other — the poem crowding around monumental hands that insist on agency, capability, and the intelligence embedded in physical labour.

Antony Gormley’s 1998 Angel of the North sits at a different historical moment — at the turn from industrial to informational capitalism — but poses a similar question about who gets to claim a work. Gormley was explicit about the sculpture’s collective origins (Hetherington, 1998): ‘I am only a very small part of this… The point about this work is that it has been built by a lot of people for a lot of people.’

During installation on 14–15 February 1998, Hartlepool Steel Fabrications Ltd reportedly attempted to hang a publicity banner from the structure to demonstrate their role in the work’s making. The project organisers, including Ove Arup & Partners, Arts Council England, Northern Arts and the European Regional Development Fund, prohibited this action, preferring instead to preserve the work’s signature artistic identity over its industrial manufacture. A workforce protest eventually produced a compromise that acknowledged the fabricators’ involvement — but only partially, and only after a fight.

As Léger hoped, “…he too will have hands like his boss. Why not?” but even today labour may physically build the artwork, but authorship still clings to the signature artist. Or, if you like, the collective makes; the individual signs.

The Rise of the ‘Mass Artist’

The artist as singular figure — solitary, gifted, touched by something beyond the ordinary — is an invention of the early Renaissance, and it has had a long run. The studio as sanctum, the artwork as signature, the artist’s biography as explanation: these remain the dominant grammar of how we talk about art. But this grammar is becoming increasingly redundant. In its place emerges a different figure — less a person than a process — the ‘mass artist’.

The ‘mass artist’ is not a type of individual. It names a shift in how art is made, circulated and understood in an age defined less by industrial labour than by cognitive, communicative and affective production. As Maurizio Lazzarato argued in his essay on immaterial labour, contemporary value increasingly derives from knowledge, information and communication rather than manual manufacture (Lazzarato, 1996). Art is not left untouched by this. It is, in many ways, its leading edge.

Negri once described art as ‘a form of life, characterised by poverty at its base, and by revolutionary will at the apex of the becoming-swarm’ (Metamorphoses, 1999). The poverty he points at is not destitution — it is a stripping away of privilege, mystique, and the aura of singular genius. At the apex: a swarm — distributed intelligence, decentralised agency, what Negri and Michael Hardt elsewhere call “the multitude” (Multitude, 2004). Art no longer radiates from a sovereign centre. It circulates through networks, accumulates in shared practices, and exceeds any individual’s capacity to claim it fully.

The theoretical groundwork for this redistribution is established in Louis Althusser’s reading of Mao’s insistence on the primacy of practice over consciousness: ideology is material, embedded in rituals and institutions rather than being merely lodged in belief (Althusser, 1971). The art world, the gallery system, the authorship contract: these are ideological structures that interpellate the artist as sovereign subject, that make the signature feel natural and inevitable. Mao’s mass line held that truth emerges from collective practice, not interior intuition (Mao, 1937). There is no personal bliss waiting to be found and expressed, no private vision the world must be made to understand. To speak of the ‘mass artist’ is to extend this understanding into cultural production — not as a political directive, but as a description of what has always been the case and is now harder to deny.

In his analysis of AI and distributed authorship, Paul Goodfellow argues that authorship now exists on a spectrum, ranging from primarily human creation to works generated through complex human-machine interactions (Goodfellow, 2024). AI does not eliminate human agency — it redistributes it across prompts, datasets, algorithms, interfaces and curatorial decisions. The artist increasingly selects, organises and contextualises rather than paints or sculpts in the traditional sense. This is not loss. It is transformation.

Herbert Read anticipated something similar. ‘To hell with culture,’ he wrote in 1941; ‘and to this consignment we might add another: To hell with the artists.’ In a natural society, there would be no privileged caste of creators — only workers. Cultural production is inseparable from the broader field of social labour (Read, 1941). Read’s polemic was deliberate provocation, but it points at something real: the art world’s investment in exceptionalism is ideological, not ontological.

Painting, too, must be situated within this field. Painting does not culminate in purified essence or transcendental depth. It remains structurally overdetermined — caught between materials, institutions, ideologies, modes of perception. Painting can now be approached as a repeatable set of operations, a refusal of authorial privilege in favour of procedural transparency and distributed awareness.

Christine Poggi’s reading of Picasso’s constructed guitars (1912–1914) shows that the artist did not simply imitate engineering techniques; he produced objects that reflected on the conditions of simplified and deskilled labour in modernity, while re-infusing the work with imagination and tactile intelligence (Poggi, 2012). As such, the work becomes less an expression of individual genius than a meditation on labour itself — its abstraction, its fragmentation, its potential reconstruction.

In this light, Bataille’s notion of art as sovereign rupture (The Accursed Share, 1949) takes on a new inflection. Sovereignty need not be located in the individual ego. The rupture becomes collective and momentary — a ‘glittering liveliness’ within shared practice, the sacred instant flashing not outside labour but within its sharing. What Bataille understood as an excess beyond utility, Negri would recognise as the surplus of affective production that capital cannot fully capture.

Mass practice requires what Althusser called theoretical vigilance — a discipline that interrupts habitual assumptions and suspends expressive reflexes (Althusser, 1971). The work only functions when authorial identity, hierarchical form and institutional reflex are overcome or provisionally held in abeyance — at that moment when processes unfold without immediate capture by brand, biography or market.

Art and life, theory and practice, subject and object are all provisional and are all contested arrangements within shared production. Theory itself becomes a practice, and painting, in this sense, remains permanently under struggle — refusing closure, refusing the comfort of an assumed essence.

Goodfellow’s analysis of AI underscores that creativity today is rarely the output of a solitary mind. Agency is distributed across collaborators, materials, technologies and infrastructures. The artist becomes organiser, navigator, and communicator within informational systems (Goodfellow, 2024). Authorship disperses into relational and embedded creativity. This does not mean art dissolves into generalised content production. On the contrary, by foregrounding its own conditions, art can demystify the fetish of the autonomous object. It can expose the networks of labour and mediation that sustain it.

In doing so, it recalls Marx’s insight that fetishism obscures the social relations embedded in commodities (Capital, Vol. 1, 1867). The ‘mass artist’, understood properly, is a way of making those relations visible rather than mystifying them further.

Such relations are not abstract. They were visible in Birmingham’s traditional Jewellery Quarter: ‘One manufactured article, which is sold retail for a penny, may go through twenty workshops before it is finished… there is perhaps no town in England where there are so many persons combining in themselves the characters of master and workman, as Birmingham, and none in which there is more observable a chain of links connecting one with another’ (The Penny Magazine, 1844). The chain of links was always there.

To relinquish the artist as singular genius is not to diminish art. It is to recognise that the creativity that connects one with another has always been social, mediated, and entangled. What changes now is that this entanglement is harder to deny.

HIS/HER LIFE BEGINS TODAY.

As Léger also said, in ‘Montjoie!’ in 1913 (Clark, 1999), “We are arriving, I am convinced, at a conception of art as vast as the greatest epochs of the past: there is the same tendency toward large scale, the same effort shared among a collectivity. If one can doubt the whole idea of creation taking place in isolation, then the clinching proof is when collective activity leads to very distinct means of personal expression.”

References

Althusser, Louis (1971) Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses, in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays.

Bataille, Georges (1949) La Part maudite (The Accursed Share).

Clark, T. J. (1999) Cubism and Collectivity in Farewell to an Idea, Episodes from a History of Modernism.

Goodfellow, Paul (2024) The Distributed Authorship of Art in the Age of AI, Arts, 13(5): 149.

Hardt, Michael and Negri, Antonio (2004) Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire.

Peter Hetherington (1998), On the side of the Angel, The Guardian.

Lazzarato, Maurizio (1996) Immaterial Labor, in Radical Thought in Italy.

Mao Zedong (1937) On Practice.

Marx, Karl (1867) Capital, Vol. 1.

Negri, Antonio (1999) Metamorphoses: Towards a Materialist Theory of Becoming.

The Penny Magazine, 1844 / https://quickanddead.wordpress.com/tag/filiere/page/2/

Poggi, Christine (2012) Picasso’s First Constructed Sculpture: A Tale of Two Guitars, The Art Bulletin, 94(2), June.

Read, Herbert (1941) To Hell With Culture.

© David Patten, 2023–2026 | [1.854 words]

Working Notes: https://davidpattenwork.com/40-the-mass-artist/

— — —

[LeChat 04.03.2026]

The essay argues that, after 1929, the only meaningful artistic production is that expressed by the “mass-artist.” This figure is defined not as an individual genius, but as a collective, constructive capacity—artistic production becomes the form of this capacity. The mass-artist embodies a shift away from the traditional, isolated artist toward a model where creativity is distributed, collaborative, and embedded in social processes.

Key points include:

Breaking down boundaries: The mass-artist’s work is not separated from educational, administrative, or physical labor, but is part of a process involving many people’s unique contributions.

Participatory and communal: Artistic activity is often the result of participatory processes, with artists acting as interpreters of community needs and concerns.

Liberated creativity: Creativity is no longer confined to specific disciplines or expertise, but becomes a ubiquitous agency—minimising mediation between artist, materials, and the everyday world.

Instability and contingency: The mass-artist operates in a space where art and non-art, being and non-being, blur, reflecting the chaotic, improvisational nature of modern life.

The text suggests that this approach leads to a radical redefinition of art and the artist, emphasising collective action, social engagement, and the dissolution of traditional artistic hierarchies.

— — —

[24.11.2024]

— — —

David Patten: The Artist, the World, and the Free Field, 2013/14

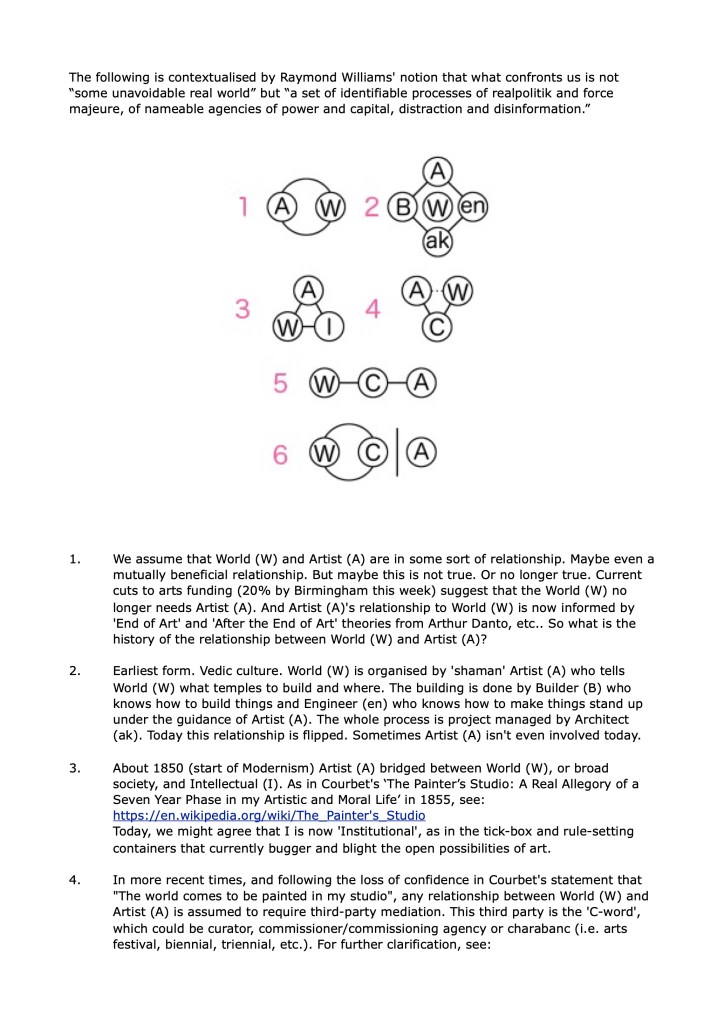

Institutional Mediation & Lebenskünstler

Raymond Williams once observed (Williams, 1983) that what confronts us is not “some unavoidable real world” but “a set of identifiable processes of realpolitik and force majeure, of nameable agencies of power and capital, distraction and disinformation.” From this perspective, the relationship between the artist and the world is not a natural or inevitable condition but historically contingent, mediated by social structures, institutions, and the politics of attention. Tracing this relationship reveals both its evolution and its rupture — from a time when the artist was central to the organisation of the world, to an era in which institutional frameworks mediate artistic engagement, and on to the present moment in which the artist can exist in an unfettered “free field,” exploring what Henry David Thoreau might call the marrow of life itself.

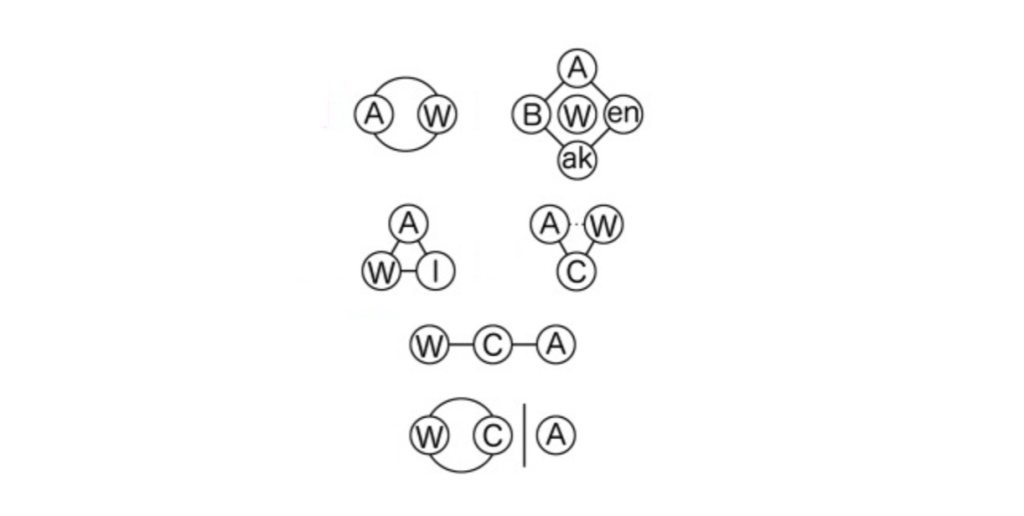

Artist and World | Origins and Early Mediation

If we define World and Artist (A) as relational categories, it is tempting to assume a mutually beneficial dynamic: that the world needs the artist as much as the artist shapes the world. Yet contemporary crises in arts funding, such as the recent 20% cuts in Birmingham, suggest that this mutuality is no longer guaranteed. Theories of the ‘End of Art’ and the ‘After the End of Art’ (Danto, 1984) also highlight a historical shift in our expectations — in short, art may no longer be essential to the social or political organisation of the world. To understand this present moment, it is necessary to trace the historical genealogy of the World

and Artist (A) relationship.

In early Vedic culture, the artist occupied a central role in the ordering of the world. Here, Artist (A) functioned as a shamanic figure, advising on what temples to build and where. Physical construction was executed by Builder (B) and made structurally viable by Engineer (en), under the guidance of Architect (ak) who coordinated and project managed the enterprise. In this schema, the artist’s authority was direct and influential: the world was materially and symbolically organised through the artist’s vision. In contemporary practice, this model is often inverted. Today, artistic interventions may be marginal or entirely absent, with projects executed without consultation with creative practitioners, leaving the artist’s influence diminished or, at best, mediated through layers of institutional authority.

Modernism and the Rise of Intellectual Mediation

By the mid-19th century, with the beginnings of Modernism, the artist’s role had shifted. The artist now mediated between the World and Intellectual (I). Gustave Courbet’s 1855 ‘The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory of Seven Years of my Artistic and Moral Life’ exemplifies this model. Courbet positioned himself as a conduit, translating social realities into artistic form. In this framework, the artist still held interpretive authority, but the relationship between society and art was now filtered through intellectual structures — ideas, critique, and cultural discourse — rather than direct social action.

Today, the ‘Intellectual’ is now the ‘Institutional’. Tick-box governance, bureaucratic oversight, and rule-bound commissioning frameworks dominate contemporary art production. Artists’ interactions with the world are increasingly mediated by regulatory, administrative, or funding bodies that codify what counts as valid artistic work. The direct channel of influence once exercised by artists like Courbet has been replaced by structures that often obscure, quantify, or standardise creative practice.

The Institutionalisation of Mediation | The ‘C-Word’

In more recent times, it is assumed that the relationship between World and Artist (A) requires third-party mediation. This intermediary — what we might wryly call the ‘C-word’ — can take the form of a curator, commissioner, or commissioning agency. The C-word functions both practically and ideologically: it defines the terms and conditions of artistic work, shapes access, and often determines which narratives or projects are legible to the public. In effect, the artist is channelled through the C-word, and their capacity to act independently upon the world is constrained by institutional language, priorities, and frameworks.

As mediation solidifies, the artist’s role becomes increasingly peripheral. The C-word assumes the primary connection to World (W), leaving the artist removed from direct engagement. In some cases, the artist becomes a contractor within a managed system, producing outcomes according to institutional specifications rather than responding to the dynamic realities of social, political, and environmental life.

Emergence of the Free Field: Lebenskünstler and Rüttler

Yet this institutionalised system also creates conditions for a radical decoupling. When Artist (A) is no longer tethered to the C-word, a free field emerges: a space in which the small ‘a’ artist can experiment, take risks, and rediscover agency. Within this field, two archetypes become instructive: the lebenskünstler and the rüttler.

The lebenskünstler is a practitioner of life itself, someone who recognises opportunity, seizes it, and consciously treats life as a work of art. Drawing inspiration from Thoreau’s injunction to “live deep and suck out all the marrow of life,” the lebenskünstler navigates both social and material worlds with intentionality, improvising and creating meaningful interventions in everyday life. Here, art is inseparable from living: it is distributed, iterative, and responsive to circumstance rather than prefigured by institutional frameworks.

The rüttler, by contrast, is a more technical and metaphorical figure. Literally translated, the rüttler refers to a machine capable of absorbing maximum rotational speed and then generating variable imbalance. Conceptually, the rüttler models the artist’s capacity to absorb, recalibrate, and redistribute the energies of the world. The artist becomes attuned to existing forces, tensions, and rhythms, and intervenes selectively to produce transformation without imposing preordained form. Both archetypes emphasise adaptability, engagement, and co-creation within a living, dynamic environment.

Returning to Kaprow: Un-Artist as Distributed Practice

The philosophical underpinning of this transition is captured in Allan Kaprow’s Education of the Un-Artist, Part II (1972). Kaprow argued that nonartists, “continuing to believe they are part of the Old Church of Art,” are limited by inherited conventions. By ‘un-arting’, i.e. dropping out of institutionalised frameworks, the un-artist, like the lebenskünstler or rüttler, operates within a distributed field of practice. In this way, agency is not concentrated in individual genius but diffused across networks of social, material, and institutional activity.

From this perspective, contemporary art becomes inseparable from collective life. The capacities traditionally associated with artists — imagination, composition, synthesis, care — are already active in public work, community engagement, and cultural memory. The role of the contemporary artist is less to generate aesthetic objects ex nihilo and more to recognise, facilitate, and amplify the ongoing creative processes that constitute everyday life.

Implications for Contemporary Practice

The historical arc from Vedic shaman to Modernist intermediary, to institutionalised artist, to free-field practitioner reveals several key insights. First, artistic practice is historically contingent: the social authority of the artist has waxed and waned, shaped by political, economic, and cultural structures. Second, institutional mediation has both constrained and defined contemporary engagement, creating both barriers and opportunities for artistic intervention. Third, the emergence of the lebenskünstler and rüttler offers a model for rethinking art as distributed, embedded, and participatory.

In practical terms, this reframing encourages artists to cultivate attentiveness, responsiveness, and adaptability. Success is measured not by the production of discrete aesthetic objects but by the capacity to activate, connect, and amplify existing networks of knowledge, skill, and care.

Conclusion

The relationship between Artist (A) and World is neither fixed nor inevitable. It has evolved from direct, shamanic authority to intellectual mediation, through institutionalisation, and now toward post-institutional, distributed models of practice. Raymond Williams’ insight — that the world is constituted by identifiable processes and agencies of power — reminds us that art is always situated within social and material structures, whether enabling or constraining. Within the free field, however, the artist can rediscover agency, becoming lebenskünstler or rüttler: figures attuned to opportunity, rhythm, and redistribution. Coupled with Kaprow’s vision of the un-artist, this approach rethinks art as a collective, embedded, and ethical practice.

In this model, art is not something imposed on the world; it is something recognised within the ongoing work of living, building, and imagining together. The artist’s authority is no longer proprietary but catalytic, and the world is no longer a passive backdrop but an active field of possibility. In embracing this distributed, post-institutional vision, contemporary artistic practice can reclaim both relevance and vitality, aligning creativity with the complex, contingent realities of the world it inhabits.

References

Danto, Arthur (1984), After the End of Art, Contemporary Art and the Pale of History

Kaprow, Allan (1972), Education of the Un-Artist, Part II

Thoreau, Henry David (1854), Walden

Williams, Raymond (1983), Towards 2000.

[draft DPv#3_23.12.2013 / ixia #2]

— — —

Un-Artist Working Notes, 2013-2014

— — —

Overview

Working note exploring how art is now defined by ‘the mass-artist’. It draws on ideas of art as a collective force that can demystify capitalist fetishes, and questions the dividing line between art and life to suggest creativity now permeates everyday experience and challenges all traditional boundaries.

[“…practice [as] glittering liveliness / drawing on Bataille’s philosophy / art = framed as sacrifice and sovereign moment = a rupture from profane, utilitarian time into the sacred instant, beyond discourse, knowledge, or ego.”]

— — —

After 1929, the only artistic production is the one expressed by the mass-artist, embodied in his constructive capacity, as though artistic production constituted the form of this capacity. And this is the story which, amid constant experimentation, leads us all the way to ’68. This is the period in which abstraction and production are intertwined: the abstraction of the current mode of production and the representation of possible worlds; the abstraction of the image and the use of the most varied materials; the simplification of the artistic gesture and the geometric destructuring of the real, and so on and so forth. Picasso and Klee, Duchamp and Malevich, Beuys and Fontana, Rauschenberg and Christo: we recognize in them artists sharing the same creative experience. A new subject and an abstract object: a subject capable of demystifying the fetishized destiny imposed by capital.

And then? What can we draw from this? ’68 comes and we reach a moment when contemporary art confronts new questions. How does the event arise? How can passion and the desire for transformation develop here and now? How is the revolution configured? How can man be remade? How can the abstract become subject? What world does man desire and how does he desire it? What are the forms of life taken by this extreme gesture of transformation? [105-106]

[. . .]

Artistic production traverses industry and constitutes common languages. Therefore, every production is an event of communication, and the common is constructed through multitudinous events. Consequently, this is how the capacity to renew the regimes of knowledge and action that — in the era of cognitive labour — we call artistic is determined. [117]

[. . .]

Art defines itself as form of life, characterized by poverty at its base, and by revolutionary will at the apex of the becoming-swarm. [121]

– Antonio Negri: ‘Metamorphoses’

[production = “constructive capacity” of individuals -> immaterial labour (knowledge, information, and communication) + transformative power of “the multitude” (a collective engaged in new forms of production and resistance) / notion of the artist as an individual creator is replaced by the mass-artist (a network of interconnected singularities) who embodies the collective, constructive capacity of society / artistic production becomes a form of expressing the ability of individuals to build and transform rather than being solely a product of the individual artist]

Working Note:

“the apex of the becoming-swarm” / Negri / ‘Metamorphoses: Art and Immaterial Labour’ = specific theoretical moment / post-Workerist* autonomist Marxist thought = the transformation of labour, art, and political resistance in the era of cognitive capitalism.

[*“The problem is, being prophets, they always have to frame their arguments in apocalyptic terms. Would it not be better to, as I suggested earlier, reexamine the past in the light of the present? Perhaps communism has always been with us. We are just trained not to see it. Perhaps everyday forms of communism are really—as Kropotkin in his own way suggested in Mutual Aid, even though even he was never willing to realize the full implications of what he was saying—the basis for most significant forms of human achievement, even those ordinarily attributed to capitalism. If we can extricate ourselves from the shackles of fashion, the need to constantly say that whatever is happening now is necessarily unique and unprecedented (and thus, in a sense, unchanging, since everything apparently must always be this way) we might be able to grasp history as a field of permanent possibility, in which there is no particular reason we can’t at least try to begin building a redemptive future at any time. There have been artists trying to contribute to doing so, in small ways, since time immemorial—some, as part of bona fide social movements. It’s not clear that social theorists—good ones anyway—are doing anything all so entirely different.” – David Graeber: ‘The Sadness of Post-Workerism’, 19.01.2008]

Negri / the Shift to Cognitive Labor = art has moved away from the solitary genius creator toward the ‘mass-artist’ = a network of interconnected, immaterial labourers.

“becoming-swarm” = distributed, and decentralised collective intelligence (the multitude) / production value through knowledge, information, and communication rather than just manual labour.

“The Becoming-Swarm” = Swarm Intelligence (shift from the industrial “mass-worker” (centralised, factory-based) to a decentralised, fluid, and self-organised multitude) + Immaterial Labour (immersed in bodies and ‘flesh’ constituting a biopolitical production that constructs reality) + Becoming (an ongoing, dynamic process of metamorphosis rather than a fixed state).

“The Apex” / Revolutionary Will = art as a form of life = poverty at its base, and by revolutionary will at the apex of the becoming-swarm.

The Base (Poverty) = precarious nature of cognitive labour (precarity, lack of ownership over the means of production).

The Apex (Revolutionary Will) = highest point of the swarming, collective action / shared cognitive labour -> construct a new, common world.

Apex = Merging Art and Life (not [just] aesthetic but ethical + political / artistic gesture becomes a revolutionary gesture / arts practice becomes a revolutionary practice [ref. Althusser + Supports/Surfaces] + Constructing the Common (collective intelligence = building ‘the common’ / new forms of life and social organisation) + Transformative Power (capacity of the swarm to transform the ‘monster’ into a new form of existence).

“the apex of the becoming-swarm” = pinnacle of collective, immaterial production where the multitude, despite its precarious existence, asserts its revolutionary will to reappropriate the means of production and construct a new, post-capitalist reality.

Barnett Newman: ’The Ideographic Picture’, 1947

— — —

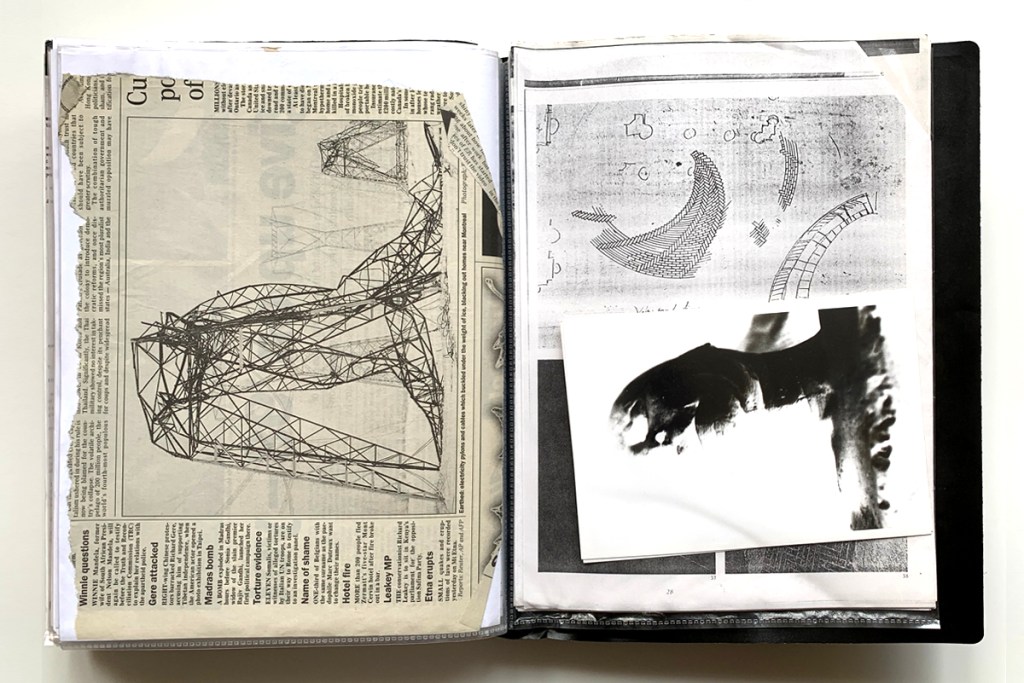

1977 | Royal College of Art / Winfrith Newburgh

“…a complex assemblage that suggests a virtual interconnection between himself, objects, and the whole interior studio environment” / “…and in contemporary painting there appeared to be scant respect for form (apart from that demanded by the conventional, rectangular boundary).”

– David Thistlewood: ‘Herbert Read, Formlessness and Form – An introduction to his aesthetics’, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984

“The main thing wrong with painting is that it is a rectangular plane placed flat against the wall.”

– Donald Judd: ‘Specific Objects’, 1965

…the moment when one is no longer able to define what divides art from non-art. Creativity, liberated from disciplinary boundaries and specific know-how, could now be exerted as a ubiquitous agency / the least amount of mediation between artist and materials / everyday world and artistic world = unstable modus operandi = chaos and contingency = “when both being and non-being, existence and non-existence, are encircled within the same form” / …just as work deviates into non-work, so art morphs into non-art…

– Gabriele Guercio: ‘The form of the indistinct: Picasso and the rise of Generic Creativity’, 2013

— — —

1977 Royal College of Art Abbey Minor Scholarship / Florence (Ghiberti / Brunelleschi)

1978 Royal College of Art Travel Bursary / Paris (Léger)

“The crudeness, variety, humour, and downright perfection [. . .] made me want to paint in slang with all its colour and mobility.”

– Fernand Léger, c1917

— — —

[21.01.2025]

“We were shifting our role away from traditional teaching on an individualistic and divisive basis, to a collaborative one, in which the sharing of experience created a relationship that, was more positive and productive.”

David Cashman: ”There are those that are the product of participatory processes and communal creative activity, whether it’s with kids or adults — lots of possibility of interaction. There’s another sort, which I’d call an interpretive one where the artist seeks information from the environment or the community where they live and they’ve got a contract with the community to interpret their needs and concerns. Then there’s another kind of artist who isn’t any of those things, who’s projecting an internal image out onto the environment, and that worries me.”

Roger Fagin: “The gallery system is not nourishing, the way our system operates now involves an appalling wastage. [. . .] We are trying to develop our role into a multiplicity of functions, so that our work as ‘artists’ isn’t separated from our educational and administrative function, or the physical labour we do, or our interactions with people with other skills. What we are doing is clearly not original or unique to one individual but to break down those concepts to create something which is the end product of a process which involves the uniqueness, originality and creativity of lots of different people interacting.”

David Cashman: “Our experience is that we get help when we ask for it, and we show there is positive energy on the move. We haven’t said we can’t get on with architects and planners and bureaucrats. We’ve gone out and taken them on. Because there are people who have vision and positive creative energy and they need to give it space to let it grow!”

– David Cashman and Roger Fagin | Islington Schools Education Project, 1975

LINK: Noose Lane, 1986 – The Jubilee Arts Archive 1974-94

Working Notes

[2008] 23.11.2023

[…filière désigne une chaîne d’activités économiques (de la matière première au produit fini)]

LINK: https://davidpattenwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/e28098the-quick-and-the-deade28099.pdf

“The…atmosphere of a place is where the mysteries of the trade become no mysteries, they are as it were in the air [and] children learn many of them unconsciously” [Alfred Marshall, ‘Principles of Economics’, 1890] and “the process…must necessarily remain continually unfinished and infinitely continuing.”

21.05.2025

[artistic production emerging in the post-1929 era / immaterial labor (knowledge, information, and communication) and the transformative power of ‘the multitude’ (a collective of individuals engaged in new forms of production and resistance in shaping the art landscape) / the artist as an individual creator is replaced by the mass-artist (as a network of interconnected singularities), who embodies the collective, constructive capacity of society / artistic production = form of expressing the ability of individuals to build and transform, rather than being solely a product of individual genius.]

12.01.2026

[mass practice requires theoretical vigilance = a collective anti-expressive discipline aimed at interrupting and dismantling assumptions / suspending authorial identity, hierarchical form, and habitual attachment -> engaging in conscious, alternative actions, behaviours and practices / non-separation can only exist as a provisional, collective, and contested arrangement towards the disciplined suspension of separative reactions within shared production]

“I have said: To hell with culture; and to this consignment we might add another: To hell with the artists. Art as a separate profession is merely a consequence of culture as a separate entity, in a natural society there will be no precious or privileged being called artists: there will be only workers.”

– Herbert Read: ‘To Hell With Culture’, 1941

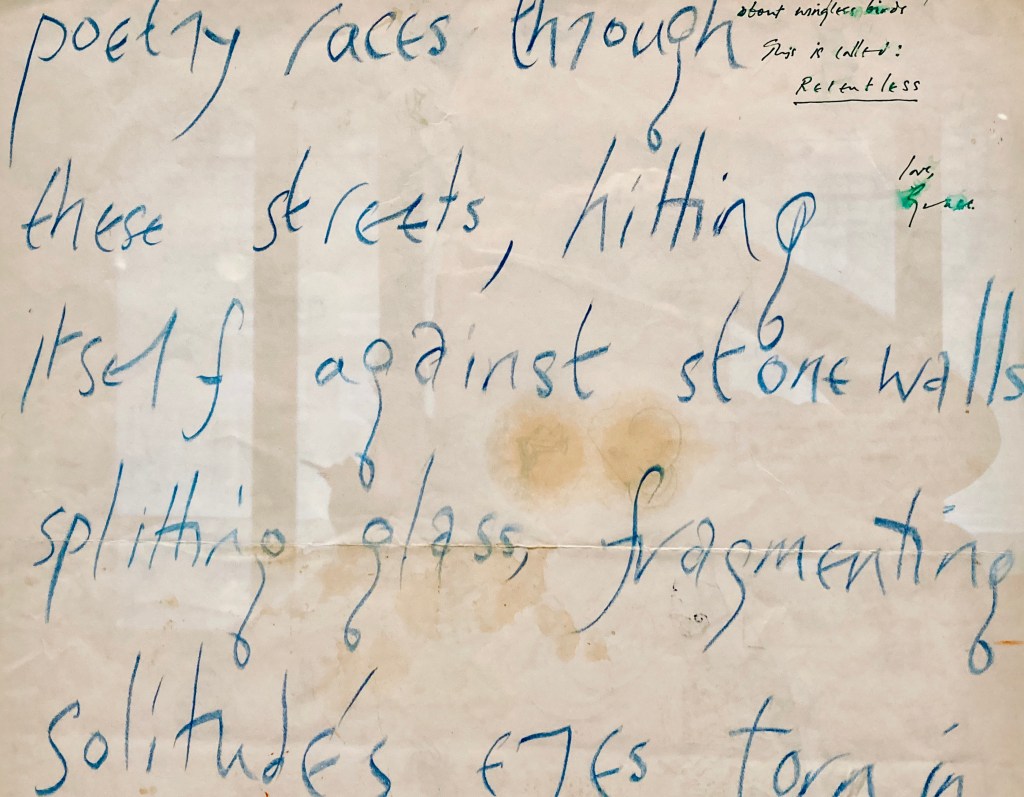

Anna Mendelssohn [Grace Dent]: Relentless, c1997

Draft summary: the primacy of practice over abstract theory / to rethink / a practice with its own material conditions and effects / and rejections / painting does not culminate in a purified essence but remains caught in overdetermined tensions between materials, institutions, ideologies, and modes of perception / a site of structural contradiction / material conditions not aesthetic mystification vs institutional approaches to painting = critical re-description of painting’s conditions / refusal of closure = painting permanently “under struggle” / [revolutionary ruptures] / concepts of interconnected practices / theory itself as a kind of practice / integrated yet relatively autonomous and mutually affecting / refusing identification with image, composition, depth, or authorial intention / non-privileging of subject, gesture, or site / de-hierarchisation: multiplicity without separation / the work functions when reactions (aesthetic, institutional, authorial) are suspended / processes are allowed to unfold without grasping / meaning is not affirmed or rejected, but circulated = equanimity as material organisation + distributed operational awareness / materialist practice insists on making conditions visible / post-studio constructed practice = suspension of separative operations (forms, identities, and reactions) -> collective production = anti-expressive discipline -> reconfigured common material conditions / theoretical vigilance = a collective anti-expressive discipline aimed at interrupting and dismantling assumptions / suspending authorial identity, hierarchical form, and habitual attachment -> engaging in conscious, alternative actions, behaviours and practices / non-separation can only exist as a provisional, collective, and contested arrangement towards the disciplined suspension of separative reactions within shared production / operationalised as anti-expressivity, distributed authorship, and procedural transparency = collective anti-expressivity that suspends habitual interpellation rather than cultivating insight or bliss.

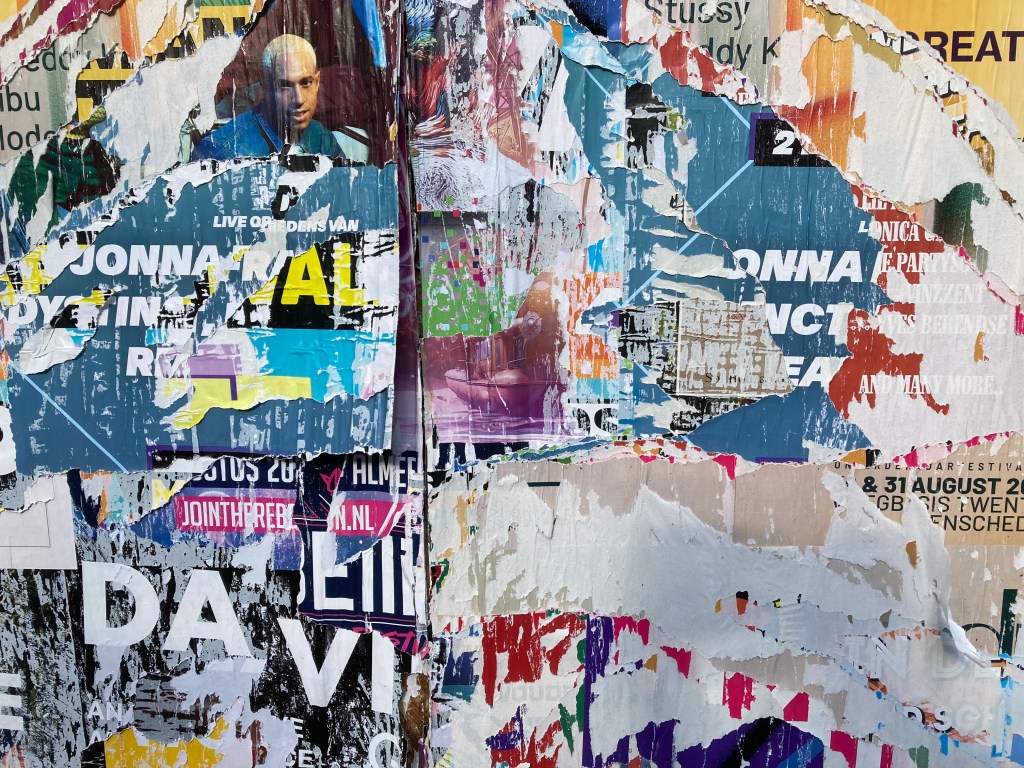

Amsterdam 16.08.2024

Artistic production = social cooperation / creativity is collective, anonymous, and productive / Art = a mode of social labour within the multitude + Artwork = a process, practice, or relation, not a finished object.

Art without expressive subject / not a subject expressing interiority / agency is distributed across practices, materials, institutions / meaning is produced structurally, not intentionally.

Berlin 07.06.2023

Painting as mass practice, not individual expression / a repeatable practice / a set of operations / a refusal of stylistic signature / practice emerges from material conditions themselves / the work is of the same order as mass labour [NOTE: Picasso ‘deskilling’ / “Picasso did not so much mimic or adopt modern engineering techniques as produce an object that reflects on the conditions of simplified or de-skilled labor in the present, while also infusing ordinary forms of labor with remarkable intellect, imagination, and tactile immediacy.” – Christine Poggi: ‘Picasso’s First Constructed Sculpture: A Tale of Two Guitars’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 94, No. 2, June 2012].

Washington DC 28.09.2024

Post-studio condition / no privileged site of production / no unified artwork as final synthesis / no authorial centre / mass artist as distributed practice = procedural or collective = a set of operations, not an object = reprogramming everyday practice, not symbolic commentary / no exterior position = an art practice which operates by reorganising the supports and surfaces of social cooperation itself.

Working Notes: June 2025

“Lethaby wrote that he didn’t believe in genius one bit, nor anything else abnormal. He ‘wanted the commonplace’. ‘Art should be everywhere. It cannot exist in isolation or one-man-thick; it must be a thousand men thick.’ [. . .] Meanwhile we can begin to live it, as some of you are doing, even in the midst of the old world and among the monuments of its failures as well as its successes.”

– Lionel Esher: ‘Architecture in a Crowded World, Vision and Reality in Planning’, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1971 | Concluding Address, Royal College of Art, 1976

Statements:

Practice is found in concrete material and social relations. The work, therefore, does not comment on something external to itself, but embraces the internal tensions and contradictions inherent to the idea of ‘beneficial practice’ and the potential of the mass-artist. Rather than relying on abstract aesthetic assumptions, this bracketing positions practice before theory, allowing knowledge to emerge through engagement with specific configurations of simultaneous events. The shift from individual, intentional authorship toward collective or relational production addresses the tension between distributed productive capacities and cultural authority. Making as ‘well-making’ becomes a non-final, non-compositional, ongoing process—a negotiation between material conditions, social cooperation, and institutional constraints.

Art is labour embedded in social life and material reality, not a privileged or separate sphere. Practice precedes theory: knowledge, value, and artistic sense emerge through doing, material engagement, and collective processes, and not through detached contemplation.

‘Beneficial practice’ is adaptive, relational, self-emptying labour grounded in everyday conditions. The ‘mass-artist’ prioritises shared production over individual expression, and emphasises cooperation, common life, and ongoing labour rather than finished objects or galleries. The work unfolds through co-creative, negotiated processes.

Art becomes an ongoing, processual activity: a way of doing and making that dissolves boundaries between individual and collective, material and social. It is ethically open and materially grounded, responsive to concrete conditions—and resistant to closure or separation from life.

— — —

[20.07.2023]

Paul Eluard, The Builders.

Cry old lazy incoherent times

Your pretensions will make us laugh

We made our cement

Our roses are blooming like a drunken wine

Our eyes are clean windows

In the blond faces of the houses of the sun desert dust

And we sing in force like giants

Our hands are the stars of our flag

We have conquered our roof everyone’s roof

And our heart goes up and down the stairs

Flame of death and freshness of birth

We have built houses

To spend the light there

So that the night no longer cuts life in two

With us love grows when our children grow up

Win eating like you win peace

Win loving like spring wins

When we speak we hear.

The truth of the carpenters

Masons roofers wise men

They carried the world above the earth

Above the prisons of the tombs of the caves

Against all fatigue they swear to last.

— — —

Hands 4

their tools resembling hands Their Laurs hand lathe tools n pants with when mapas fold their pants A mountains TOTOR Sura ili on Sunday Has at tres d’apings he will free himself, it’s abstract THEY DO That. hout to his wife, to his daughter ALA Baconcierge Totor is chic MEMORY of MATAKOW LOOK ALIKE PAC to those of their patronpas he is disgusting… ocellus of the prelate once a week.A As long as ea) machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot not Sporte, demolished, built, very high com are approaching very low, under the water in the sky the marching EVERYWHERE in this world THEIR HANDS FOR THEM Are presented Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS Why NOT? hopefully there will be gloves. WHY NOT.? SAMACHINE ITS CA AMA PLANT Roche West on the road- SAVIE Starts Today

version #4

their tools resembling hands Their / hand lathe tools / pants with when / fold their pants A mountains / on Sunday Has at / he will free himself, it’s abstract THEY DO That / to his wife, to his daughter / is chic MEMORY of / LOOK ALIKE / to those of their / he is disgusting / of the prelate once a week. / As long as / machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot not / demolished, built, very hight / are approaching very low, under the water in the sky the marching EVERYWHERE in this world THEIR HANDS FOR THEM Are presented Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS Why NOT? hopefully there will be gloves / WHY NOT? / ITS / PLANT / West on the road / Starts Today

Hands 5

tools Raising hands look like To Their tools in their hands pants are vi when euro plantologis my not fold there TOTOR folds on Sunday has mountains in slices he will break free, it’s abstract THEY DO sapat to his wife, to his daughter once a week.MAÏA KOK Liger ALA asa concierge. Totor is classy. MEMORY of LOOK ALIKE PAC to those of their patronas he is disgusting… As long as da machine His hands are heavy! in his arms there Jates and Tramille a lot rorte, demolished, built, very high very low, under water In the sky EVERYWHERE Damn the world THEIR HANDS are the marching For them Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS PRESENT Why not? alantous he will have gloves. WHY NOT? SAMACHINE, HIS FACTORY CA Apprache he is on the road=” SAVIE Starts Today

version #5

tools Raising hands look like To Their tools in their hands pants are / when euro / my not fold there / folds on Sunday has mountains in slices he will break free, it’s abstract THEY DO / to his wife, to his daughter once a week / classy. MEMORY of LOOK ALIKE / to those of their / he is disgusting… As long as / machine His hands are heavy! in his arms there / a lot / demolished, built, very high very low, under water In the sky EVERYWHERE Damn the world THEIR HANDS are the marching For them Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS PRESENT Why not? / he will have gloves. WHY NOT? / HIS FACTORY / he is on the road / Starts Today

Hands 6

their tools look alike Their hands Their tools in their hands When maps their pants a pan unfold TOTORrapi on Sunday mountains at very many trees he frees himself, it’s abstract sapat to his wife, to his daughter THEY DO de & Lig once a week.MAÏA Kowk LOOK ALIKE NOT TO THE I have her concierge. Toton is chic. MEMORY to those of their patronpas he is disgusting… ocellus of the relat As long as aj machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot horti, demolished, built, very high are approaching very low, underwater in the sky the marching Around the world THEIR HANDS For Are THEM Then he will also have PRESENT hands like HIS BOSS WHY NOT? anyway he will have gloves. FORQual PAS.? SAMACHINE, ITS FACTORY → IT Approaching ballast on the road- SAVIE begins Today

version #6

their tools look alike Their hands Their tools in their hands When maps their pants a pan unfold / on Sunday mountains at very many trees he frees himself, it’s abstract / to his wife, to his daughter THEY DO / once a week. / LOOK ALIKE NOT TO THE I have her concierge. / is chic. MEMORY to those of their / he is disgusting… / of the / As long as / machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot / demolished, built, very high are approaching very low, underwater in the sky the marching Around the world THEIR HANDS For Are THEM Then he will also have PRESENT hands like HIS BOSS WHY NOT? anyway he will have gloves. FOR / ITS FACTORY / IT Approaching ballast on the road / begins Today

— — —

version #4

their tools resembling hands Their / hand lathe tools / pants with when / fold their pants A mountains / on Sunday Has at / he will free himself, it’s abstract THEY DO That / to his wife, to his daughter / is chic MEMORY of / LOOK ALIKE / to those of their / he is disgusting / of the prelate once a week. / As long as / machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot not / demolished, built, very hight / are approaching very low, under the water in the sky the marching EVERYWHERE in this world THEIR HANDS FOR THEM Are presented Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS Why NOT? hopefully there will be gloves / WHY NOT? / ITS / PLANT / West on the road / Starts Today

version #5

tools Raising hands look like To Their tools in their hands pants are / when euro / my not fold there / folds on Sunday has mountains in slices he will break free, it’s abstract THEY DO / to his wife, to his daughter once a week / is classy. MEMORY of LOOK ALIKE / to those of their / he is disgusting… As long as / machine His hands are heavy! in his arms there / a lot / demolished, built, very high very low, under water In the sky EVERYWHERE Damn the world THEIR HANDS are the marching For them Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS PRESENT Why not? / he will have gloves. WHY NOT? / HIS FACTORY / he is on the road / Starts Today

version #6

their tools look alike Their hands Their tools in their hands When maps their pants a pan unfold / on Sunday mountains at very many trees he frees himself, it’s abstract / to his wife, to his daughter THEY DO / once a week. / LOOK ALIKE NOT TO THE I have her concierge. / is chic. MEMORY to those of their / he is disgusting… / of the / As long as / machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot / demolished, built, very high are approaching very low, underwater in the sky the marching Around the world THEIR HANDS For Are THEM Then he will also have PRESENT hands like HIS BOSS WHY NOT? anyway he will have gloves. FOR / ITS FACTORY / IT Approaching ballast on the road / begins Today