Working Notes: June 2025

“Lethaby wrote that he didn’t believe in genius one bit, nor anything else abnormal. He ‘wanted the commonplace’. ‘Art should be everywhere. It cannot exist in isolation or one-man-thick; it must be a thousand men thick.’ [. . .] Meanwhile we can begin to live it, as some of you are doing, even in the midst of the old world and among the monuments of its failures as well as its successes.”

– Lionel Esher: ‘Architecture in a Crowded World, Vision and Reality in Planning’, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1971 | Concluding Address, Royal College of Art, 1976

Abstract

1. Art ≠ Object

Art is not a product to be bought or hung; it is a pathway—a way of thinking, labouring, and living. [Lethaby] “Art is not a thing; it is a way.”

2. Creation = Thinking + Making

Every act of art-making brings together conceptual thought and physical labour. The artist is not separated into ‘maker’ and ‘thinker’, but embodies both roles as Lethaby insisted.

3. Artworker = Maker / Artist = Worker

Reject the myth of the artist as a mystic exception. Embrace the artist-as-worker—an identity rooted in both skill and creativity, formed in community and grounded in labour, not in elite distinctions.

4. Labour (invisible) + Ideology = Art’s Function

Art frequently conceals the true work behind it and serves to reinforce class structures through mystification and ideology. Reclaim art = render visible its labour and expose its ideological roles.

5. Freedom = Collective Realization = Collective + Concrete + Visible

Artistic freedom arises not from ideals of transcendence, but through collective, practical acts arising from real human capabilities—collaborative, embedded, and materially grounded.

6. (Art – Illusion) – Ideological Consciousness = Transformation

Art stripped of ideological illusion—its mystique—as well as the consciousness upheld by class domination. Only then can it transform into a genuine expression of collective human potential.

7. New Art = Rethink (consciousness) + Reframe (process) + Rebuild (collectivity)

Building art as a way involves rethinking cultural legacies, reframing creativity and engagement, and rebuilding community-based, accessible structures of expression and learning.

“We have to refound art on community service as the well-doing of what needs doing.”

– W.R. Lethaby: ‘The Town Itself / A Garden City is a Town’, 1921

Art = accessible and participative = an arena for awareness, critique, and transformation = concrete, collective human agency / shifting production, ownership, and social relation = collective, human creativity, rooted in material, social contexts

Summary

Art isn’t just an object or aesthetic artifact—it’s a mode of work and living, a purposeful approach to labour and everyday life.

Historical & Theoretical Foundations

W.R. Lethaby’s challenge of the fine art vs. craft hierarchy / insisting art is defined by the integration of thinking and making—“art is not a thing; it is a way.”

• Silvia Federici on “invisible labour” and Peter Bürger on avant-garde theory, arguing modern art often hides the social value and invisibility of labour.

• [Yugoslavia] artist-as-worker models—first honouring, then undermining them as neoliberal pressures emerged.

• [Art, Class, and Ideology] / Goran Đorđević’s Marxist text (“On the Class Character of Art,” 1976) as central:

# Religion and art act as class tools, reinforcing elite power structures.

# As capitalism grew, it elevated the “Artist” as a near-divine exception, legitimising social hierarchies.

# Art functions ideologically—even in socialist or totalitarian regimes—by shaping consciousness to align with ruling interests.

Transformative Practice

To dismantle art’s ideological role:

# a radical shift in production and ownership

# a conscious rejection of art as elitist illusion

# new forms of expression rooted in real human, collective creativity.

Art emerges from engagement with real, natural human capacities—not mystical ideals.

Rethink art as a way of working and being, deeply tied to labour, community, and tangible reality—not elite mystique or romantic ideals.

— — —

Katja Praznik, Art Work: Invisible Labour and the Legacy of Yugoslav Socialism, Toronto : University of Toronto Press, 2021, 217p

…examines the paradox of artistic labor as both socially valuable and systematically devalued / feminist critiques of invisible labor / modern understandings of art—as autonomous, personal expression—have obscured its status as work deserving compensation / socialist Yugoslavia early revolutionary period / artists = “art workers” / later shift towards neoliberalism = redefined artists as “entrepreneurs” / historical roots of artistic labor’s invisibility, influenced by Romanticism, avant-garde movements, and feminist theory (especially Silvia Federici [#1] and Peter Bürger [#2]) > Yugoslavia’s 1950s self-management system = artists legal and institutional support but also created tensions with the Marxist goal of democratizing art > 1970s = persistent elitism of the art system, exemplified by figures like Goran Đorđević [#3].

1980s Slovenian alternative movements / rejection of socialism’s institutional framework and promotion of artistic autonomy / aimed at liberation + aligned with neoliberal ideologies = undermined the welfare protections for artists = precarity

— — —

W.R. Lethaby, a British architect, educator, and key figure in the Arts and Crafts movement, was a strong advocate for the concept of the art worker—someone who combined artistic vision with manual craftsmanship. He rejected the rigid separation between the fine arts and the applied or decorative arts, promoting the idea that all creative labor had dignity and value.

Lethaby believed that artists and craftsmen should not be divided into hierarchical categories, such as “artist” vs. “artisan” or “designer” vs. “maker.” Instead, he emphasized the unity of design and execution, which he saw as central to true artistic work. This idea was rooted in a broader social and moral critique of industrial capitalism, which he believed had alienated workers from the creative process and devalued skilled labor.

Lethaby’s view: “Art is not a thing; it is a way.”

This aphorism reflects his belief that art was not an elite product but a mode of working and living that could—and should—be accessible to all. He saw the art worker as someone who approached labor with care, skill, and creativity, no matter the medium.

In education, particularly as the first principal of the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London (founded in 1896), Lethaby implemented these values by encouraging integrated training in both design and manual skills. His views helped lay the groundwork for modern design education and influenced later movements that sought to dissolve the boundary between art and labor.

— — —

#1. Silvia Federici: ‘Wages Against Housework’, 1974 / “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work. They call it frigidity. We call it absenteeism.”

#2. Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde has had a major influence in the United States since it was translated into English in 1984, mainly through the writings of art critics linked to the journal October (Benjamin Buchloh, Douglas Crimp, Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Craig Owens). For these authors, the discussion of Bürger’s theses was a way, first, of redefining their own postmodernist position at a time when it had been weakened by the emergence of a postmodernism that was considered reactionary and, second, of revising their conception of the history of modern art by counterposing Clement Greenberg’s formalist, depoliticized modernism with a re-evaluation of the critical or utopian dimension of the historical avant-gardes. However, the context in which the original German version of Bürger’s work had been published a decade earlier was completely different, marked by a crisis in literary studies and a renewal of Marxist aesthetics. This article attempts to retrace the conditions of this intellectual transfer, from the obliteration of the book’s original context to its repositioning in the American postmodernist debate. It also offers a key to reconstructing the theoretical and strategic issues that confronted postmodernist art criticism from the 1970s to the 1990s. Finally, it shows how these debates contributed to a lasting redefinition of the major categories of twentieth-century art historiography. / https://journals.openedition.org/bssg/1222?lang=en

Peter Bürger’s theory of the avant-garde—particularly from his 1974 book Theorie der Avantgarde—continues to shape contemporary art discourse in several key ways, even decades after its publication. Though some aspects have been critiqued or adapted, his core insights remain influential in discussions about art, institutions, and politics.

1. Critique of the Art Institution

Bürger argued that the historical avant-garde (e.g., Dada, Surrealism) aimed to dissolve the boundary between art and life, challenging the autonomy of the art institution. This remains central to:

• Institutional critique (e.g., artists like Hans Haacke or Andrea Fraser)

• Social practice art that seeks real-world impact beyond gallery walls

• Ongoing debates about decolonizing museums and dismantling elitist structures in the art world.

2. Neo-Avant-Garde vs. Historical Avant-Garde

Bürger made a critical distinction:

• Historical avant-garde = genuinely subversive, anti-institutional

• Neo-avant-garde (e.g., post-WWII experiments) = reabsorbed into the art market.

Contemporary theorists and curators still use this framework to:

• Question whether today’s experimental art is truly radical

• Critically assess the co-optation of protest aesthetics by the market.

3. Ongoing Revisions and Challenges

Bürger’s binary (avant-garde = revolutionary, neo-avant-garde = recuperated) has been challenged by scholars like Hal Foster, who argue for a more dialectical view—that neo-avant-garde art can both reproduce and resist institutional forces.

But even in critique, Bürger’s model is the baseline:

• It’s still the reference point for defining art’s political potential

• It frames how we assess art’s autonomy vs. its social embeddedness.

4. Global Perspectives

In recent years, scholars have applied Bürger’s concepts to:

• Non-Western avant-gardes (e.g., Latin American, African, and Asian movements)

• Transnational critiques of modernism and the Western canon

• The global art market’s ability to neutralize dissent.

This shows the adaptability—and limits—of his Eurocentric model, prompting global re-readings.

In Summary:

Peter Bürger’s theory remains influential because it provides:

• A clear historical framework for understanding radical art movements

• A powerful critique of how institutions neutralize subversion

• A lens for interrogating art’s political and social ambitions.

#3. Goran Đorđević (Goran Djordjevic; 1950, Yugoslavia) / “former artist”

Graduated in electrical engineering in Belgrade and visual studies from MIT. From 1972, when he joined the SKC Gallery in Belgrade, an artists/art historians run space, he had been appearing in public and exhibiting until 1985. From 1979 onwards Đorđević realized a series of works based on copying, such as Short History of Art (1979/81) and Harbingers of Apocalypse(1981). He later helped to organize “The Last Futurist Show” by Kasimir Malevich (1985), Walter Benjamin’s lecture: “Mondrian 1963-1996” (1986), and The International Exhibition of Modern Art (Armory Show) (1986).

Since 1985 he has not been active as an artist, except for a brief period (1988-91) as a member of the Amateur Art Society Jedinstvo [Unity] in Belgrade under the pseudonym Adrian Kovacs when he participated at exhibitions of the Society with his black-and-white self-portraits, still lives, and copies of Cézanne [1], but also at the exhibitions like the Moscow Portraits (Moderna Galerija, Zagreb, 1990; Mestna Galerija, Ljubljana, 1991); Jugoslovenska dokumenta (Sarajevo, 1989); The New Langton Arts, San Francisco, 1991; Slovenske Atene, Moderna Galerija, Ljubljana, 1991) [2].

From 1992-2014, he was a doorman (using any name but “Doorman”) of the Salon de Fleurus, New York, a live reenactment of Gertrude Stein’s Paris salon from the early 20th century, housing copies of her collection of modern art. Đorđević also collaborated on the project International Exhibition of Modern Art Presents Alfred Barr’s Museum of Modern Art in New York that was part of the official selection of Serbia and Montenegro on the Venice Biennale in 2003. Since the opening of the Museum of American Art in Berlin (2004), he became its technical assistant (using any name but “Technical Assistant”) responsible for external activities (temporary exhibitions, lectures, etc).

— — —

Goran Đorđević: ‘On the Class Character of Art’, The Fox, New York, 1976

SUMMARY

This text presents a Marxist critique of art and religious consciousness, arguing that both have historically served as tools of class domination. Here is a summary of its key points:

Core Argument:

Human history is primarily shaped by class relations, with the ruling class controlling not only the means of production but also cultural and ideological spheres—such as religion and art—to maintain power.

Religion as Class Tool:

• Organized religion emerged in societies where a minority economically dominated the majority.

• Religious consciousness centers around abstract, eternal concepts (e.g., God, creation from nothing) that serve to legitimize this control.

• These concepts have no empirical grounding in nature or society and are used to justify hierarchical structures.

Art and the Rise of Capitalism:

• As capitalism emerged, the authority of God waned, and the bourgeoisie promoted the idea of the exceptional individual.

• The figure of the Artist was born—someone seen as uniquely gifted and near-divine in their creative powers.

• Art thus became another tool to justify and naturalize social inequality, symbolizing a human struggle between the real (natural, conditioned existence) and the ideal (divine, unconditioned freedom).

Art as Ideological Instrument:

• Historically, art has served the ruling class by shaping consciousness and legitimizing existing power relations.

• In both capitalist and totalitarian systems, art does not degrade under control—it reveals its true function as an ideological tool.

• Even in socialist societies, this ideological function often persists because art continues to be supported and affirmed without critical analysis of its class character.

Critique of Socialist Cultural Policy:

• Socialist societies sometimes fail to recognize the reactionary nature of traditional artistic consciousness.

• Continuing to support such forms of art reinforces outdated, alienated cultural mechanisms.

• A genuine revolutionary transformation requires not just changes in the relations of production, but also a critical reevaluation of cultural heritage and artistic institutions.

Vision for the Future:

• True freedom lies in new forms of consciousness and activity grounded in the real, natural capabilities of human beings.

• Art, as it currently exists, represents an illusion of freedom, not its realization.

• Society must break from fear of the Unknown—rooted in deep socio-economic anxieties—and instead embrace a naturalistic understanding of the world and human potential.

Conclusion:

The text argues that both religious and artistic consciousness are historically shaped by and serve class interests. For true emancipation, society must critically reexamine these traditions, end their material and ideological support, and develop new, liberating forms of thought and expression rooted in real human potential.

FULL TEXT

The known history of human society is principally a history of class relations. The ruling class, controlling the existing productive forces and relations of production, also seek to control the existing relations in other spheres of human activity. The presence of organizes religious consciousness is quite understandable in those forms of social organization in which direct control (above all, economic) of the few over majority of the members of society is allowed.

The existence of religious consciousness was basically always manifested by the acknowledgement and acceptance of the existence of the following concepts: Absolute, Universal, Ideal, Eternal: which leads to a spontaneous assertion of one of its elementary concepts usually known under the name of God. These concepts represent attributes that primarily relate to the concept of God. I feel that it is also necessary to name another very important divine attribute and that is the concept of creation “from nothing” (ex nihilo). By the present knowledge of relations in nature (including man and society as forms of its expression), it seems there is not just one phenomenon with which we could relate the concept of creation. This bring us also to the conclusion that this concept only has any sense if the concept ‘God’ has. Put simply. A being that exists as a result without a cause is the only being that can create. (The human being is certainly not that being).

It is understandable why the appearance of early capitalism corresponds roughly to the decrease of the authority of God. The social consciousness then current placed man in a particularly inferior (humiliating) position in respect to God and did not correspond to the then new productive forces. The still young bourgeoisie encouraged the view of strong, powerful and exceptional men who are above the other members of society. These men have gained their position in society thanks, above all, to “exceptional” qualities. It is interesting that during this period there appears a definite consciousness of the Artist and of Art. The Artist is an exceptional, particularly gifted and talented man who, thanks to his capability for creating has to accede to Ideal, Eternal, Universal, absolute values (i.e. to attain God). The renaissance of Antique Gods, bearing human qualities is necessary for the making of the model of an exceptional man with divine characteristics (superman). So, art as “creative” activity (by of course “exceptional” men), serves as yet one more “proof” for the justifiability of given class relations. On the one hand we have the human being biologically, economically, sociologically, psychologically, profoundly conditioned; on the other stands his spiritual opposite and (unfortunately) his ideal, the being possessing the absolute qualities of-God. Especially in past centuries, art represents a specific document on the primeval struggle in man between the aspiration to reach the supernatural and natural possibilities – the divine and the human. This process was conditioned by the degree of development of productive forces and the relations of production, and the results of this process were used to justify and confirm these relations. Thus: art in its real and practical function was and remains one of the instruments of the ruling class in the process of the forming of consciousness and in the process of governing the majority. Revolutionary change of the social order is primarily conditioned by qualitative changes in the relations of production. This the control over labour and its fruits would be fundamentally altered.

The decentralization of society and the possibility of direct decision making over the results of one’s own work, offers conditions for the establishment of more humane relations between people and between man and his environment, thereby permitting a greater degree of liberty for each member of society as well as for the community in general. I feel that supporting and producing art that is a result of class relations (in the service of the ruling class) is a way of expressing reactionary consciousness in a society which is working on building new interpersonal relations (e.g. as in our society).

Take the character and role of art in a totalitarian society: it does not represent art’s degradation, on the contrary it shows art’s true face which in other circumstances is more or less successfully masked. In capitalist society, since the functioning and organization of art are based on the interests of the ruling class the demand for the abolishment of support for such an activity and the demand for its overcoming, as consciousness as well as activity, are conditioned by the demand for a qualitative change, of relations of production and of the positions of those forces in society to which art is necessary. This is a necessary but not a sufficient condition. Apart from the qualitative change in the relations of production, it is indispensable to clearly determine the reactionary character of the artistic consciousness and activity, this provides conditions for the overcoming of that consciousness and that activity on the level of society- achieved primarily by denying material support to the parasitic mechanism and system of institutions that seek and have the right to possess these alienated means thanks to the existence of the results (products) of artistic activity- the work of art- and thanks to the very affirmative, existing, relation of socialist society towards art. In countries that are building socialist relations in society, not only is the class character of the artistic consciousness not understood , on the contrary this consciousness is upheld and asserted through corresponding activities that in fact mean permitting the existence of those forces and mechanisms which by their nature have very little in common with the true endeavours for better, more humane relations in society and for a greater degree of freedom for every human being in that society. I believe that the decision about accepting or rejecting art, considered as consciousness as well as activity on an individual level, is an inalienable right of every human being that should not be questioned, as is also the case with the individual right to expression of the other forms of religious consciousness in socialist society.

That which is indispensable to our society at this moment is a truly critical analysis of the whole cultural inheritance, from the point of view of the essential need of our community. (I’m thinking here of the educational system in particular). At the same time, we must seek new forms of activity, new ways of thought, that would be the result of a consciousness of the real, natural possibilities and tendencies of the human being in the sense of augmenting the degree of individual and collective freedom.

(Art is primarily the results of an illusion of freedom, and not a way of expressing the liberties of the human being. Every activity of which the goal is the assertion of an artistic consciousness represents at the same time the prolongation of that illusion).

It is necessary to free ourselves from the primeval fear of the Unknown (which is really a function of economic, sociological, psychological and other factors) for fear of the Unknown is the basic precondition for the appearance of any form of religious consciousness. We must understand and truly accept that the Unknown is also nature. In a certain way, it is our own nature.

“The call to abandon illusions about their conditions is the call to abandon a condition which requires illusions.” – K. Marx

Source: Goran Đorđević: ‘On the Class Character of Art’, The Fox, New York, 1976, p. 163-165

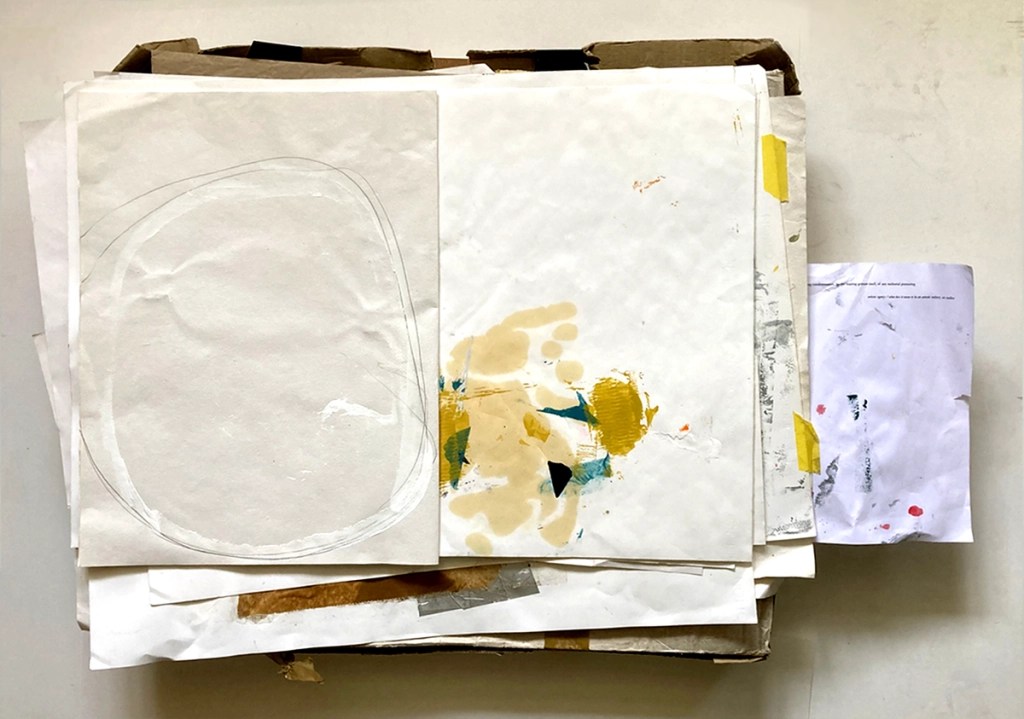

Text: ordinary techniques produced a fragile, improvised object / the selection and inventive manipulation of unlikely, preformed elements / physical (nontranscendent) acts such as cutting and folding paper substitute for traditional drawing / subvert / exchange of the codes of painting and sculpture / a mingling of optical and haptic modes / in the gap between de-skilled labor (which might be carried out by anyone) and highly skilled, “immaterial” labor that preserves a sense of artistic spontaneity in its messy, inefficient facture.

…a stack of art papers or sketchbook pages, likely from an artist’s studio or personal archive.

Overview

• The stack includes multiple sheets of paper in various conditions, some clean, others paint-stained or marked.

• It rests atop a flattened cardboard box or similar backing, with paper hanging loosely over the edges.

• The scene feels informal and process-oriented, suggesting a work-in-progress or archival collection of creative experiments.

Details

• Left Page (Top of Stack):

• White paper with light pencil sketching, primarily a large, loose oval or organic shape.

• Minimalist and abstract — likely an underdrawing, draft, or compositional guide.

Right Page (Next in Stack):

• Paint marks in yellow, ochre, teal, black, and beige.

• Appears to be the result of brush tests, palette wiping, or abstract painting techniques.

• There’s masking tape along the right margin — perhaps used to hang it up or secure it during work.

Far Right Page (Peeking Out):

• A printed or typed page with some faint text visible near the top.

• Paint smudges and creases imply it was used practically, not preserved for presentation.

• May be a statement, reference text, or instruction page used in the studio.

Interpretation

• This image documents a studio practice — informal, raw, and rich with process.

• The materials evoke the gestural, intuitive aspects of art-making.

• Could be part of a process archive, sketch dump, or a “working pile” that reflects thinking-through-doing.

Conceptual Notes

If you’re analyzing or curating this image, consider:

• Material memory: Each page holds traces of gesture, decision, and experimentation.

• Form as residue: These are not finished works, but remnants or tools of making.

• The image as a whole acts like a portrait of an artist’s method, not a single artwork.

Image shows two side-by-side screenshots taken using Google Lens. Each one depicts a collage-like black and white artwork overlaid with detected/translated text.

Léger: ‘The Hands, Homage to Mayakovsky’, 1951

TEXT CUT AND PASTED TOGETHER / form of visual or concrete poetry, possibly inspired by Dadaist or Constructivist aesthetics. [“On a garden bench such a new publication lies; I rejoice if the passing wind half opens and unintentionally animates aspects of the book’s exterior — several of which, because of the flood of things perceived, maybe nobody has thought of since reading existed.” – Mallarmé]

Drawings of hands / each hand seems stylized differently, possibly to emphasize:

• Manual labor

• Gesture and expression

• Tool use or transformation.

Constructivist visual language collage as a political statement about labor, automation, and the erasure or transformation of human identity through work.

Further Notes

Ecclesiastes 9:10 NIV: “Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might, for in the realm of the dead, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning.”

— — —

Christine Poggi: ‘Picasso’s First Constructed Sculpture: A Tale of Two Guitars’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 94, No. 2 (June 2012), pp. 274-298

The materiality, facture, formal structure, and presentation of the 1912 Guitar show it to be related to contemporary collages and constructions. Picasso’s reuse of fragments of existing pictorial codes and materials constitutes a form of bricolage, while his de-skilled technique allows the paper Guitar to reflect on contemporary labor conditions and to become a conceptual model for subsequent works.

[. . .]

Beginning in 1912, de-skilled forms of labor employing tools designed for rapid execution increasingly usurped the place of traditional, time-consuming craft in Cubist works: letters were stenciled; wood grain was simulated with a painter’s comb; literal texture and depth were added with sand, plaster, or dust rather than mustered through the devices of illusion; and color was applied with commercial, unmixed Ripolin enamel or with pasted and pinned bits of machine-printed paper. / …a rigorous reduction in the level of required craft; concerns with proper workmanship and the efficient use of tools and materials (engineering) were jettisoned. / de-skilling and re-skilling / a fragile, improvised object whose virtuosity lies in its new conception of sculptural practice as bricolage—construction through the selection and inventive manipulation of unlikely, preformed elements. Resolutely physical (nontranscendent) acts such as cutting and folding paper substitute for traditional drawing (for disegno [Italian word for drawing or design, carries a more complex meaning in art, involving both the ability to make the drawing and the intellectual capacity to invent the design] / render literal, and thereby subvert, the conventions of pictorial illusion as well as the related conventions of relief sculpture. The result is a brilliant crossing and exchange of the codes of painting and sculpture, and a mingling of optical and haptic modes of address / and highly skilled, “immaterial” labor that preserves a sense of artistic spontaneity in its messy, inefficient facture. / Picasso did not so much mimic or adopt modern engineering techniques as produce an object that reflects on the conditions of simplified or de-skilled labor in the present, while also infusing ordinary forms of labor with remarkable intellect, imagination, and tactile immediacy.

— — —

[Jeffrey Weiss] …constructed fabrication: a narrow set of means / composed of physically autonomous elements / a crossover of pictorial and sculptural means / 1912-1913 / an effort to displace, obstruct, or even resist technical facility— the facility of the hand / lines are drawn with an incremental, even deliberately halting accretion of strokes / roughness or provisionality remains largely, at times wholly, undisguised / relative (or handheld) mechanicity prevails / cutting, pinning, and attaching or affixing / technique of tearing = delicacy of the convention of touch / mechanical drawing = depersonalisation = resist the sensibility of touch or the technical facility of the hand (in the context of picture-making)

…the contingent object / disavowal of technical facility / a fragment…is affixed: secured / the object articulates its own contingency through a device that brings the liberty of its parts to momentary or suspended rest / fabrication, defabrication, and refabrication / a “finished” object is forever deferred / the condition of deferral / a momentary state of rest / the object’s temporality / the specific manner in which the objects exist in time = a theory of the momentary actual and historical fate of the aesthetic object = [Picasso quote] “To me there is no past and future in art.” / “Arts of transition do not exist” / “All I have ever made was made for the present and with the hope that it will always remain in the present.” -> Picasso /cardboard Guitar 1912 / William Rubin (MoMA) 1973

— — —

Christine Poggi: ‘Defiance of Painting’, Yale University Press, 1992

…pictorial and poetic practices—collage, papiercolle, constructed sculpture, and parole in liberta (free-word poetry). It represents an attempt to engage a field whose very complexity and experimental character preclude a reassuring sense of closure / anti-aesthetic materials / the arbitrariness of pictorial conventions / tableau-objets / in real space independently of the picture frame or the pedestal / a willingness to view representational conventions as arbitrary and unstable and to subvert any attempt on the part of the viewer to grasp the work’s meaning in an unequivocal manner / a desire to define their artistic practice as the antithesis of the manual work of the artisan or painter of signs, in favor of a more elevated view of artistic creation as a product of the imagination.

— — —

20.07.2023

To Fernand Léger

Cry old lazy incoherent times

Your pretensions will make us laugh

We made our cement

Our roses are blooming like a drunken wine

Our eyes are clean windows

In the blond faces of the houses of the sun desert dust

And we sing in force like giants

Our hands are the stars of our flag

We have conquered our roof everyone’s roof

And our heart goes up and down the stairs

Flame of death and freshness of birth

We have built houses

To spend the light there

So that the night no longer cuts life in two

With us love grows when our children grow up

Win eating like you win peace

Win loving like spring wins

When we speak we hear.

The truth of the carpenters

Masons roofers wise men

They carried the world above the earth

Above the prisons of the tombs of the caves

Against all fatigue they swear to last.

– Paul Eluard

— — —

version #4

their tools resembling hands Their / hand lathe tools / pants with when / fold their pants A mountains / on Sunday Has at / he will free himself, it’s abstract THEY DO That / to his wife, to his daughter / is chic MEMORY of / LOOK ALIKE / to those of their / he is disgusting / of the prelate once a week. / As long as / machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot not / demolished, built, very hight / are approaching very low, under the water in the sky the marching EVERYWHERE in this world THEIR HANDS FOR THEM Are presented Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS Why NOT? hopefully there will be gloves / WHY NOT? / ITS / PLANT / West on the road / Starts Today

version #5

tools Raising hands look like To Their tools in their hands pants are / when euro / my not fold there / folds on Sunday has mountains in slices he will break free, it’s abstract THEY DO / to his wife, to his daughter once a week / is classy. MEMORY of LOOK ALIKE / to those of their / he is disgusting… As long as / machine His hands are heavy! in his arms there / a lot / demolished, built, very high very low, under water In the sky EVERYWHERE Damn the world THEIR HANDS are the marching For them Then he will also have hands like HIS BOSS PRESENT Why not? / he will have gloves. WHY NOT? / HIS FACTORY / he is on the road / Starts Today

version #6

their tools look alike Their hands Their tools in their hands When maps their pants a pan unfold / on Sunday mountains at very many trees he frees himself, it’s abstract / to his wife, to his daughter THEY DO / once a week. / LOOK ALIKE NOT TO THE I have her concierge. / is chic. MEMORY to those of their / he is disgusting… / of the / As long as / machine Their hands are heavy! in his arms Girls have worked a lot / demolished, built, very high are approaching very low, underwater in the sky the marching Around the world THEIR HANDS For Are THEM Then he will also have PRESENT hands like HIS BOSS WHY NOT? anyway he will have gloves. FOR / ITS FACTORY / IT Approaching ballast on the road / begins Today

— — —

Les mains, à la mémoire Maïakowski [Mayakovsky] 1951

Huile sur toile, 89 x 130.

Leurs mains ressemblent à leurs outils,

Leurs outils à leurs mains

Leurs pantalons à des montages, à des

troncs d’arbre.

Un pantalon est vrai quand il n’a pas de pli.

Totor aura un pli le dimanche.

Il se libère, c’est abstrait,

ça plaît à sa femme, à sa fille, à sa concierge.

Totor est chic,

Il est déguisé…

une fois la semaine,

ses mains sont lourdes à ses bras,

elles ont travaillé beaucoup.

Porté, démoli, construit.

très haut, très bas, sous l’eau, dans le ciel,

partout dans le monde,

LEURS MAINS SONT PRÉSENTES

elles ne ressemblent pas à celles de leur patron

pas à celles du prélat bénisseur.

Tant que la main travaillera pour ceux-là,

elles ne changeront pas.

Mais les temps approchent où la machine.

Travaillera POUR EUX.

Alors, il aura aussi des. mains comme son

patron.

Pourquoi pas ?

à son tour, il aura des gants

Pourquoi pas ?

SA MACHINE, SON USINE, ça approche,

il est sur la route

SA VIE COMMENCE AUJOURD’HUI.

F. Léger

Collection particulière.

Hands, in memory of Malakowski 1951

Oil on canvas, 89 x 130.

Their hands are like their tools,

Their tools in their hands

Their pants to assemblies, to

tree trunks.

Pants are real when they don’t have a crease.

Totor will have a crease on Sunday.

It frees itself, it’s abstract,

it pleases his wife, his daughter, his caretaker.

Totor is classy,

He is disguised…

once a week,

his hands are heavy in his arms, they worked a lot.

Worn, demolished, built.

very high, very low, under water, in the sky,

all over the world,

THEIR HANDS ARE PRESENT

they do not resemble those of their patron

not those of the benevolent prelate.

As long as the hand works for those,

they will not change.

But the times are approaching when the machine

Will work FOR THEM.

So, he will also have hands like his boss.

Why not ?

in turn, he will have gloves

Why not ?

HIS MACHINE, HIS FACTORY, it’s getting closer,

he is on the road.

HIS LIFE BEGINS TODAY.

F. Leger

Private collection.

Les Mains. Peinture. Poème à la mémoire de Maïakovski,vers 1950. Huile sur toile, 160 cm x 120 cm, Musée Fernand Léger

http://www.savoirs-alpesmaritimes.fr/Media/Fiches-pedagogiques/musee-Fernand-Leger/leger11

ChatGPT 19.06.2025:

• Hands as Tools and Identity:

The poem emphasizes how “hands” are intertwined with “tools” and labor, symbolizing human skill, craftsmanship, and identity in creation. The workers’ hands have “worked a lot” — worn, built, demolished — marking them as creators, makers, tied intimately to their work.

• The Role of Machines and Change:

The poem signals a turning point where “the machine will work FOR THEM.” This suggests a shift from human hands driving the work to machines (or AI) taking on the labor. The “hands like his boss” and “gloves” imply that the human’s role is changing — perhaps becoming more like the machine, or more controlled by it.

• Abstract vs. Real / Traditional vs. New:

The mention of “pants are real when they don’t have a crease” versus “Totor will have a crease on Sunday” hints at tension between reality and abstraction or tradition and modernity. This might metaphorically relate to art: traditional craftsmanship (real, hands-on) vs. art mediated or created by abstracted, coded processes (machines, AI).

• New Beginnings and Transformation:

“His life begins today” indicates a new phase, possibly the dawn of an era where AI and machines reshape not only labor but creativity and art-making itself. The human may not be erased but transformed.How does this relate specifically to AI and art making?

• Human vs. Machine Creativity:

The poem reflects on the current state where art (or labor) is made by human hands—intimate, skillful, embodied. But it foresees a time when machines (AI) will create “for them,” shifting the nature of artistic creation.

• Collaboration or Replacement:

The shift hints at AI as both a tool and an autonomous agent in art-making. The line “So, he will also have hands like his boss” might suggest humans adopting machine-like precision or the merging of human and machine roles.

• Artistic Identity and Authenticity:

There’s an underlying question of what happens to artistic identity when machines take over creation. Are the hands (human touch) still “present”? Or will the machine’s influence reshape the very nature of art?

• Embracing Change:

The poem ends on an optimistic or at least open note—“His life begins today”—implying that this new era with machines (AI) can lead to new forms of art and creation, rather than simply threatening traditional methods.

The poem comments on the evolving relationship between AI (machines) and art-making by highlighting a transition from human-centered craftsmanship to machine-driven creation. It explores questions of identity, authenticity, and transformation in art, suggesting that AI could both redefine and collaborate with human creativity rather than simply replacing it.

— — —

14.06.2025 [ref. Generic Creativity]

In the contemporary reflections, creativity and consciousness are seen as emerging from gaps—voids—between being and non-being, nature and culture, material and immaterial. These “gaps” or “fragments” do not annihilate difference but instead preserve singularity, alerting us to origin points—places where presence and absence negotiate meaning.

The creative act, thus, is not about adding new content but reframing what already exists—moving with minimal mediation between life and art. This act is sensitive, specific, and potentially transformative. Like the sage, the artist or thinker must confront the tension between transcendental awareness and residual structures (like ownership or authorship), continually reshuffling known forms to glimpse the unknown.

Ultimately, both the spiritual and the artistic strive toward a state where distinctions dissolve—between Self and Other, form and formlessness, poetic play and lived reality—ushering in a blissful unity that challenges dominant systems and affirms a new kind of presence rooted in absence.

— — —

20.06.2025 [ref. LH]

This rich meditation explores how deep engagement with art, vision, and poetic sensibility leads to a transformative rupture in perception. Drawing on thinkers like Hölderlin, Carl Einstein, Pema Chödrön, and Wordsworth, it proposes that the “poetics of unfixing” destabilizes fixed realities, opening a “hallucinatory interval” where unseen truths emerge. Art, in this view, doesn’t represent the world but reconfigures it, creating subjective, mythic realities beyond conventional understanding. This is not passive seeing but active vision—a spiritual, vertical movement away from material certainty toward openness, groundlessness, and the infinite. Art becomes a force of disruption, freedom, and potential future becoming.

— — —

21.06.2025 | Summary of two texts:

The work resists traditional structure and coherence, favouring an informal, process-driven approach where conventional order and artistic hierarchy are absent. Instead, it embraces a raw, experimental mode of creation using everyday materials and actions—cutting, folding, stacking—blurring boundaries between painting and sculpture, skilled and unskilled labour, and finished and unfinished states. It becomes a record of gesture, thought, and making—a provisional archive of spontaneous, physical experimentation rather than a resolved, singular artwork.

— — —