…and Leger said, “What are you doing here?” and I said: “I’m moving in.” And it turned out the walls of my studio were also the walls of his.

– Charlotte Perriand, 1999

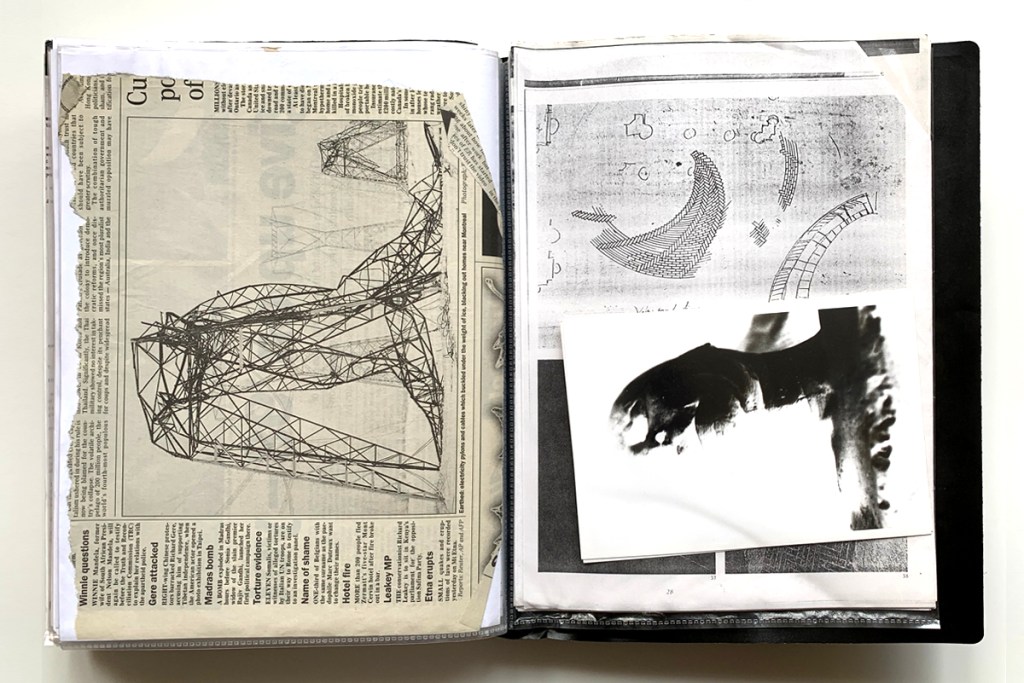

Léger’s statement, contained in a lecture given at the Sorbonne in 1934 [‘From the Acropolis to the Eiffel Tower’, unpublished lecture], was as applicable to the 1950s as to any other time: ‘One must will oneself to live within the context of what is true. To learn and look at facts as they are, whether they are beautiful or ugly, but devoid of any decorative veil… All objective facts surrounding us are rich with living material — one lives in a world that is marvellous, one that very few people know how to look at and understand. Why hide it all? Why dissimulate it, scale it down, camouflage it?’

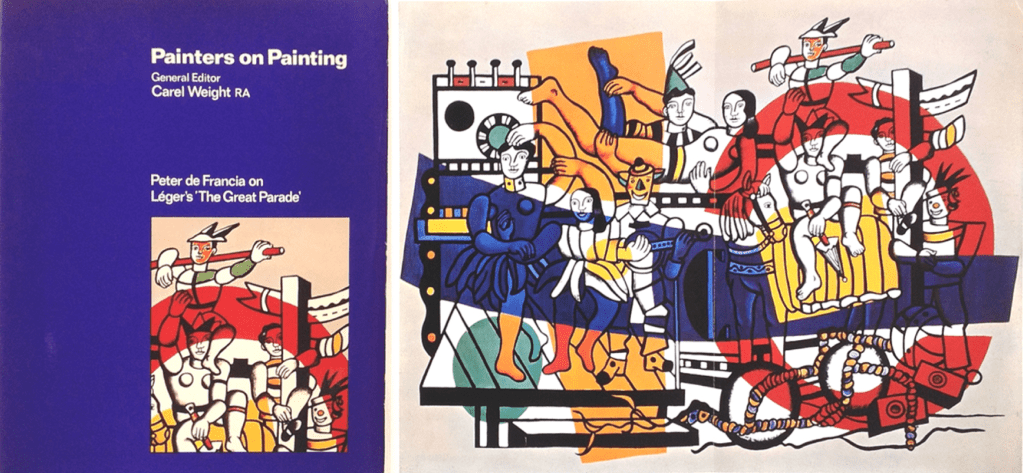

– Léger, quoted in Peter de Francia: ‘Fernand Léger’, Newhaven and London, Yale University Press, 1983

Painting as Material Culture | Statement 2026

Painting is not simply an image. Material culture theory emphasises that objects do not merely reflect social life; they actively mediate and structure social relations (Miller 1987; Gell 1998). In this sense, paintings function as social agents.

Painting becomes a site of negotiated interaction between hand, tool, medium, gravity, viscosity, and drying time. Material resistance is not an obstacle but a generative constraint shaping form. This resonates with Tim Ingold’s argument that making is not the imposition of form onto matter but a correspondence between human movement and material processes (Ingold 2013).

Althusser’s notion of art as a practice embedded within ideological and material apparatuses clarifies that painting does not stand outside social determination (Althusser 1971). Painting can disrupt habitual perception, producing what Althusser called a “distance” from ideology by reorganising sensuous experience rather than directly transmitting political messages.

Painting as material culture is the play of perception and attention — colour relations, spatial depth, texture, rhythm, touch and scale. Painting shapes how we learn to see, dwell, and orient themselves in time and space.

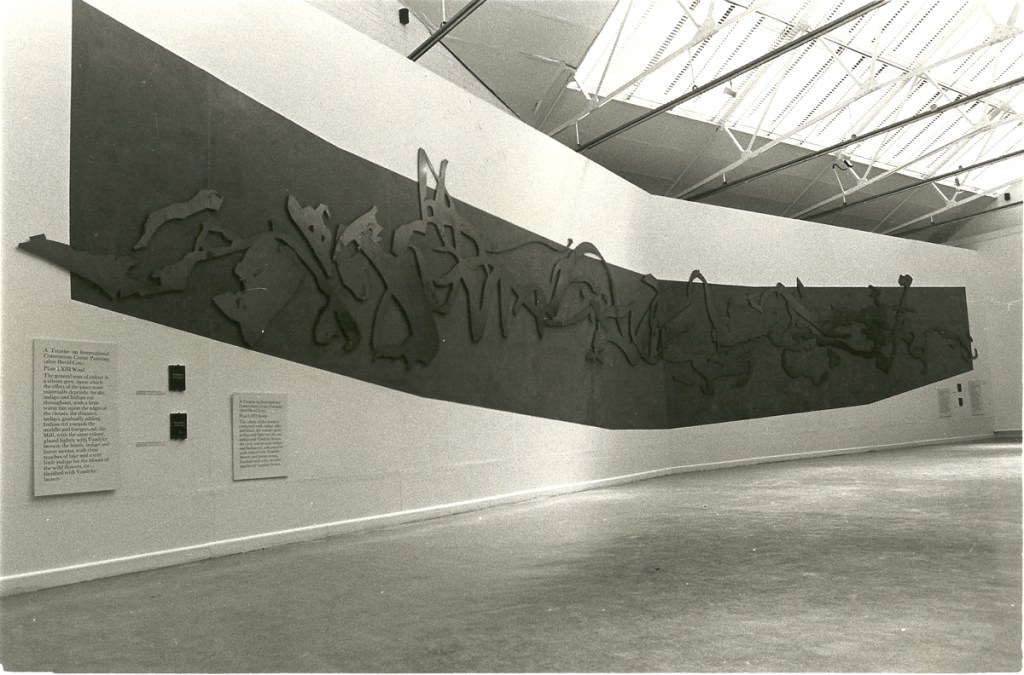

Socially engaged or collective painting practices foreground painting’s role as a shared material process, emphasising labour, collaboration, and public encounter over isolated authorship. In this way, painting functions less as a finished object and more as a relational event, embedded in communal making and circulation.

Painting is neither merely representation nor pure aesthetic form. It is a materially situated practice that produces objects, perceptions, relations, and values simultaneously with — and within — matter, labour, sensation, and social life.

References

Althusser, Louis (1971), Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses / Lenin and Philosophy.

de Francia, Peter (1983), Fernand Leger

Gell, Alfred (1998), Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory.

Ingold, Tim (2013), Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture.

Miller, Daniel (1987), Material Culture and Mass Consumption.

[296 words]

— — —

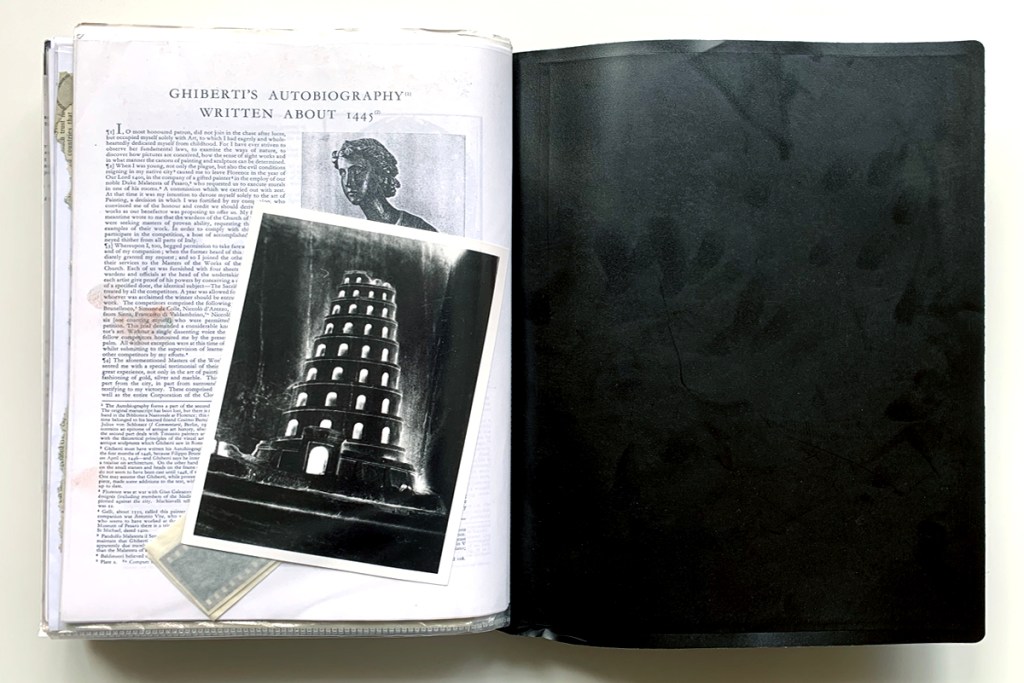

1977 Royal College of Art Abbey Minor Scholarship / Florence (Ghiberti / Brunelleschi)

1978 Royal College of Art Travel Bursary / Paris (Leger)

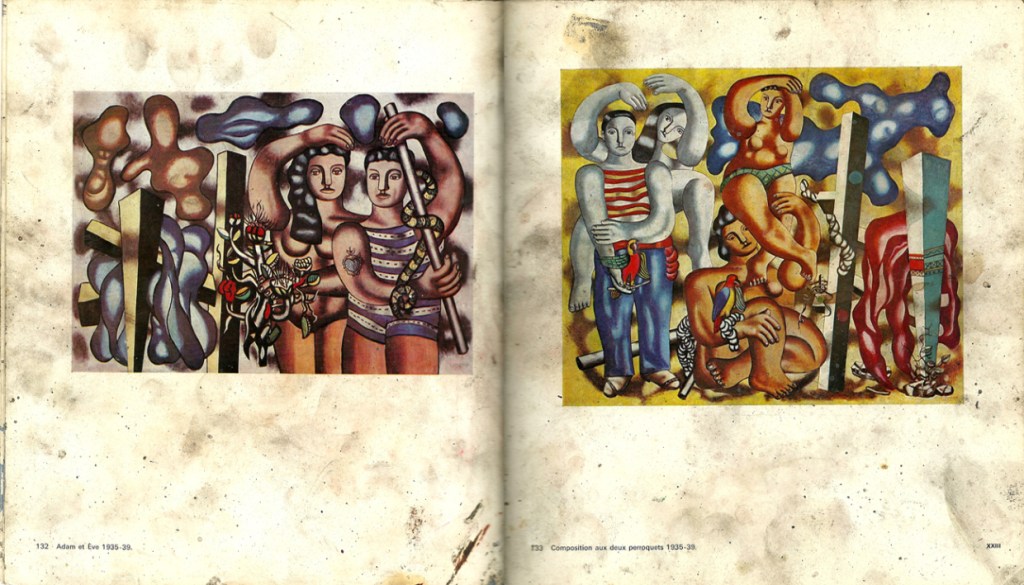

“Considérée par Léger comme l’une de ses œuvres les plus abouties, la Composition aux deux perroquets fut exposée à Paris, une seule journée, le 15 avril 1940, dans l’atelier de son amie Mary Callery, avant d’être envoyée à New York, et d’y demeurer tout le temps de la guerre. / Elle est exposée au Museum of Modern Art, du 27 décembre 1940 au 12 janvier 1941, puis à Oakland, l’été suivant. Léger la fait revenir à Paris à l’occasion de l’exposition rétrospective qui lui est consacrée au Mnam par Jean Cassou, à l’automne 1949. Il l’offrira au Musée en 1953.”

“Writing to Gide in December 1902, Paul Valéry, that most perceptive of critics, stated: ‘To tell the truth I think that what one calls art is destined either to disappear or to become unrecognisable.’ In context his statement was extraordinary prophetic of what was to ensue and of what has taken place.”

– Peter de Francia: The State of British Art: A Debate, Day #2, ICA, London, 1978

This road is dominated by that desire for perfection and total liberation which produces saints, madmen and heroes. … The rarefied nature of its artistic formula makes it extremely vulnerable. It is a light, luminous and delicate structure, coldly emerging from the surrounding chaos.

– Fernand Leger: ‘De l’art abstrait’, 1931

[17.11.2025]

Polychrome, functional synergy and art integration in the France-USA Memorial Hospital of Saint-Lô, Normandy (1948-1965), Paul Nelson, architect.

Wartime New York—with its dynamic commercial, architectural, and technological infrastructure—offered renewed possibilities for the realization of Léger’s projected chromatic vision. In 1942, for example, he was invited by the architect Paul Nelson to speak to a committee of the US Housing Authority in Washington, DC, which was charged with providing housing for war workers, about his ideas for using color in town planning. Léger outlined a theory that involved combining colors to produce different effects in various areas of the town: in the center, brilliant colors would be combined in a “cocktail” in order to reflect the excitement and variation of its activity. Outside the city center, color was to become less intoxicating, with one strong color balancing more neutral tones in residential areas to produce a more intimate atmosphere that would have a positive emotional effect on the inhabitants. While Léger met with sympathetic supporters in the United States, including Nelson, his leftist political views and modernist aesthetic were never to garner backing from officials. When read against the backdrop of World War II, Léger’s idealistic belief in human emancipation through the careful organization of color and light appears as a gesture of hope for the future, for a radical rebuilding and restructuring of Europe (and France specifically) based on collective ideals, and for overcoming the chasm opened up between rationalist thought and feeling.

– Meredith Malone, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, 2011